DIRECTOR: Well, here we are on German soil,

My friends. Tell me, you two have stood

By me in bad times and in good:

How shall we prosper now? My toil,

Indeed my pleasure, is to please the mob;

And they’re a tolerant public, I’ll admit.

The posts and boards are up, and it’s our job

To give them all a merry time of it.

They’re in their seats, relaxed, eyes opened wide,

Waiting already to be mystified.

I know how to content popular taste;

But I’ve a problem here, it must be said:

Their customary fare’s not of the best —

And yet they are appallingly well-read.

How shall we give them something fresh and new,

That’s entertaining and instructive too? […]

My aim is our success: I must adopt

The proper method of achieving it.

What tool’s best, when there’s soft wood to be chopped?

Consider who you’re writing for! They come,

Some of them, from sheer boredom; some

Arrive here fully sated after feeding;

Others again have just been reading

The newspapers, God help us all.— Goethe, Faust (tr. David Luke)

Recently, the German-language paper Die Zeit (The Times) published an op-ed titled “Eine Neue Aufklärung” — “A New Enlightenment” ($). The subtitle inquired: “What does Alex Karp, founder of the surveillance company Palantir, think? An answer can be found in Frankfurt, in his dissertation on Martin Walser.” The op-ed, penned by a professor at Kings College who specializes in the study of terrorism and political radicalization, Peter Neumann, focuses on Dr. Karp’s dissertation, Aggression in der Lebenswelt, written more than 20 years ago at the Goethe University in Frankfurt, as a lens for better understanding Dr. Karp’s own Weltanschauung with respect to the company that he co-founded in 2004 and has run as CEO ever since, Palantir.1

Having not only read Dr. Karp’s dissertation, but also having translated the whole of it into English — at times painfully, I recall one session at Starbucks working through a section of the Theodor Adorno quoted in his dissertation where I wanted to bang my head against the table that was inevitably smeared with the aged, sticky-sweet residue of some unicornicinno or otherwise clawing my eye out with a paper straw; I settled instead for downing another cortado2 and self-soothing by picking off the chocolate chunks from a brownie — I had a number of thoughts in response.

Of course, yet again, I really am the wrong person to write this, because, to flesh out my responses and steelman Dr. Karp’s point of view against “A New Enlightenment” required me to delve into the critical theory that informs his background. Therefore, all of this is written with the caveat that I have very little formal academic training; when it comes to matters of philosophy, I might as well be illiterate3; unlike both Drs. Karp and Neumann, I do not have a doctorate and never have really done proper research, and certainly not in this domain, making me deeply unqualified from the jump, and if all of this were not terrible enough, then there is the fact that leftist thought is totally foreign to me to begin with.4

For me, reading Dr. Karp’s own original stomping grounds in the Frankfurt School and then out to critical theory more broadly, trying to understand it on its own terms, is like trying to communicate with the octopus aliens in Arrival, driving on the opposite side of the road, or engaging in basic life tasks like eating or brushing my teeth with my non-dominant hand. Everything about it is not only different, but inherently opposite all of my own natural political predilections, which, if you forced me to enter them into a Midjourney prompt, would be something like: “Catholic-infused technofuturist anarcho-capitalist monarcho-liberal in shades of vaporwave, outrun, neon-lit night feeling; set to Gregorian chant lo-fi with mallsoft beats; Jacques Ellul on the rocks with a twist of von Balthasar”. None of this, she says with a wave of her hand, seems like anything remotely compatible with understanding critical theory.5 (Well, maybe the von Balthasar.)

However, it was only through listening to a lot of Dr. Karp that I found a new love for the West which I now hold very dear. So, I cannot help but be annoyed, irritated, and somewhat personally offended by what I perceive to be not only an extremely cursory but also unjust treatment of him, even if the absolute chasm in my political orientation combined with the significant deficits in my educational background and intellectual capacity make me very much the wrong person to write this defense.

But, the Lord writes straight with crooked lines, and I can only pray that His grace is extended to these meager, crooked lines of mine too.

“Whose Best Turned To Evil Through Devilish Cunning”

First, some discussion of context is necessary.

In my own time torturing other Americans at parties by discussing things like European politics, I often find that there is a very two-dimensional, overly reductionist view of Europe, as if it were some sort of extension of Disneyland — a petting zoo for American tourists, but with baguettes and berets and gelato. But Europe is complicated, and Germany — I betray my own affections here — is perhaps the most complicated among them. One may nod one’s head in response and say “But of course! Zee Nazis!” Well, yes, of course, Zee Nazis, but what Americans don’t by and large appreciate is the whole reason of why the Nazis came into being in the first place, and it perhaps is more complicated than simply pointing to the economic and political damage wrought by the Treaty of Versailles — as indisputably terrible Versailles was to the German people.

This ground is well-covered by a book extensively discussed in Dr. Karp’s dissertation, Die verspätete Nation (I translate the title as The Belated Nation, but no English translation of the book has yet been published; it also seems to be out of print in German) by Helmuth Plessner, published in 1959. Interestingly, while Dr. Neumann plainly states in the op-ed that the subject of his research into Dr. Karp’s worldview is this dissertation, he never discusses at all The Belated Nation, Plessner, or the ideas that Dr. Karp explores about Lutheran interiority in German culture. Personally, I found Dr. Karp’s reading of Plessner in his dissertation to be absolutely fascinating, so I will quote from it at length:

Like [Theodor Adorno’s] “The Jargon of Authenticity”, “The Belated Nation” is an attempt to lay bare the social background upon which the Nazis relied. Adorno and Plessner proceed from the assumption that the prevailing economic and political circumstances of the time certainly prepared the ground for National Socialists, but that those alone are not sufficient explanations for the success of the Nazi movement:

“The resonance capability for the National Socialist politics and ideology can only be understood in a limited way as out of the direct conditions of Versailles, inflation …, the partisan political structure and from the mismatch of the lower middle class between ‘18 and ‘33 to the established parties, as well as from the radicalizing effect of the significant unemployment since ‘29.” (Plessner, 1994: 12)

In comparison to Goldhagen’s82 argument, according to which an eliminatory antisemitism was the basis for the National Socialists, the approach of Plessner is rather more narrowly tailored on the presuppositions that underlie such thought. The starting point is surprisingly similar, however: to explain the National Socialists only with an eye to the economic and political landscape of Germany is to disregard the cultural specificity of the reaction to it. […]

Beginning with the belief “that there are not two Germanys”,84 one of brilliant writers, artists, and scientists, and one of barbarians, Plessner reconstructs the historical background, out of which these both parts of Germany emerge. The retardation of political developments is his theme: his field is that Lebenswelt, that refused democratic institutions even the validity they had required for their continuance.

In his description of the political circumstances, Plessner is not concerned with a superficial description of those political forces that supported the Nazis, but rather with the interactions of political institutions with an entrenched interiority in the Lebenswelt. Therefore, Plessner begins with an analysis of the significance of the German defeat in the First World War. Defeats alone are no carrier of particular cultural or political meaning. They can trigger a regeneration process, or, in German-speaking areas (from here on: Germany), excite a societal regression, a movement also, that singles out the defeats in a specific manner. It only then has success if it manages to relate the already pre-interpreted attitudes to society back to itself, so that a message emerges out of it that can be culturally understood. Therefore, the disappointment of a lost World War cannot alone explain the emergence and institutionalization of the National Socialist movement.

“There are defeats that even a proud people can accept. It only needs to feel as if, through it, it has awakened and been reminded of its true purpose. For Germany the defeat was intolerable, because it was senseless like the war and because it remained senseless.” (Plessner, 1994: 36)

Plessner writes further:

“(Germany’s) protest against the peace of 1919 is not simply the expression of its defeat, also not the mere response to the ideas of democracies and middle-class freedom with which the adversary won against them. It is the protest against the historical calamity, that refuses one of the central European states a path to national unity much more on the basis of its ambiguous tradition than over simple violence.” (Plessner, 1994: 37)

Plessner describes the interaction between undemocratic political attitudes and interiority. It makes a catastrophe out of a defeat. […] The authoritarian state does not hold sway only over the heads of its subjects, but also simultaneously roots itself deep in their thought. On the basis of this preliminary decision, Plessner can emphasize the decay of democratic institutions without either overlooking or over-evaluating structural difficulties (for example, the defeat).

[…] Plessner argues namely, that Germany in its radical, inward-facing rejection of the Catholic tradition coming from Rome, missed the opportunity to partake in those civilizing processes out of which (also in its educated rejection) the concept of the nation arises, which makes redundant the idea of “das Volk”.85 The concept of a nation not only safeguards against fascism because it is reflected in a form of a constitution, but also because the nation acts as identity-building for the citizens of a country. To be French, English, or American makes sense in the only context of a particular political culture. It requires an equality of the members of a society before those criteria that determine the belonging to a society. So nation and identity are, for Plessner, interwoven in the Lebenswelt:86

“For the Anglo-Saxon states, Calvin became essential. For France, the Enlightenment. Both powers have, in their development, a core decisive interest in the transmutation of the state out of the spirit of personal freedom. Both powers work in the direction of the interior way of life, which in France the separation of church and state guarantees. The secularization does not touch the state in its pure expediency, in its parliamentary formality. It would only come into conflict with it if it wanted to make claims on the individual person, and certainly in the metaphysical sense.” (Plessner, 1994: 62)

To be proud of membership in a country with a nation-state tradition means, ultimately, to be a constitutional patriot. On German soil, however, this statement implies a recourse to an existing original right in a time before the founding of the state, which is either inherent or may never be completely bestowed:

“It is not the real provenance of a people from a prehistoric time that determines the historic picture of the state, but rather, the idea of law, freeing and reconciling, consciously retained with conceptual dignity, blotting out the burden of past existence.” (Plessner, 1994: 63)

The primary problem is cultural, because it is related to the structures that people repair in order to “understand” something: “There the original sense (of a democratic) apparatus is no more understood. (In such countries) they lack … the corresponding preconditions that date back to religion” (Plessner, 1944: 62). Understanding is the key word. It suggests faulty structures that lend statements their meaning. Such structures are produced in the Lebenswelt. Therefore, in Plessner, both the place that supplies validity as well as the position of this place in the maintaining of political institutions can be located. The motivation of the involved actors is hence brought to the foreground. Then, insofar as political bodies are reliant on their ability to make actions in the Lebenswelt understandable, the maintenance of such institutions is only possible against the background of the communicability in the culture. Plessner knows, of course, that no equating of the Lebenswelt and system follows out of this insight. He therefore describes the structural constraints that have influenced the actions of the decision-makers. It is also clear to him that not every decision made by a political body is problematized in the Lebenswelt.

That is also not the aim. For Plessner is asking the question, in what relationship do the underlying political structures of a society stand with respect to their culture. His answer reads that such structures must be created in the Lebenswelt of a society, because the Lebenswelt ultimately gives those structures their interpersonal meaning, that members of a society find, until further notice, unquestionable. In other words, that denoted characteristic of democracy which is described by Plessner as metaphysical pretentiousness is a self-understanding of the Lebenswelt, which need not be questioned because it “easily” counts as a shared assumption of social action in the Lebenswelt. […] To summarize, it can be said that because Plessner takes the meaning of the Lebenswelt for politics seriously, he must explain why the Germans have willingly supported a disturbed movement.

In the historical development of German Protestantism, Plessner sees the most important source of those patterns of meaning that make possible comprehensibility (also about oneself) and so explain the motivations of people’s actions. The animated new orientation toward the interior from Luther changed the imprint of structures of Lebenswelt. It consequently influenced those who either refused religion or belonged to other confessions:

“Because … Protestantism becomes the leading power of life, it imprints new people, even too where they still adhere to the old beliefs.” (Plessner, 1994: 56)

And elsewhere:

“So the existence of a Lutheran-style state church in a confessionally divided milieu not only generally impacted the direction of secularization, but also summoned into life a specific Lutheran-religious worldliness and worldly piety, that gained form in the ideology of German politics and worldviews.” (Plessner, 1994: 66f.)

Luther’s theology provided German culture with meanings that, as assumptions, became self-evident in everyday communication and, for that reason, are not exposed to any problematization under normal circumstances:

“On Luther’s side, on the other hand, in the relationship between piety and professional work that creativity had to arise, because it draws on creativity itself and establishes that bond between the temporal and the eternal an identity-giving intimacy, which sanctifies the profane through the spirit of action. Inherent within this is the change of function of religion from ecclesiastical to worldly life. Therefore its consummation in existence and in concept of the culture is a Lutheran category and a German fate.” (Plessner, 1994: 75)

These structures challenge an attitude to the world that first, follow the general Protestant movement in strongly emphasizing the world here below and second, in different forms of Protestantism (principally Calvinism) diverge, insamuch as evangelism is supposed to be the most important confirmation of human moral behavior. The phenomenon of a Christian thought turned inwards, that is at the same time relating to the world (worldly) and is ultimately turned away from it (piety), Plessner names “worldly piety”.

Luther’s doctrine implies that the moral content of action is not to be measured on its results, but instead on its efficacy with which one can follow the teaching of God. In the world of action, also the world in which the truth of God should be proven, action becomes measured on its “interior” criteria. An action that is purely “worldly” experiences contempt, because it profanes the place of a holier work. The divide between Calvinism and evangelical theology is further expanded through its different attitudes toward society; owing to its propensity to interiority, the children of Luther stand relatively indifferent to political engagement, if not even skeptical to it. They prefer to concern themselves with “the essentials”, namely, family and work87:

“Through the fact of an authoritative church and the inner-minded anchoring of the idea of vocational calling, a dualism is developed between an areligious state life and a religious, extra-ecclesiastical vocational and private life. Calvin’s doctrine put a stop to this privatization of faith. Through its sharp hold on the principle of supremacy of the church above the state, through the claim of God’s dominion, a different relationship between right belief and civil-societal life was created from the beginning.” (Plessner, 1994: 74)

[…]

The function of religion in the production of meaning in the Lebenswelt and in the legitimization of political bodies is namely established, in Germany, out of the doctrine of Luther. Worldly piety flourishes next to secularization. Worldly piety disenchants the culture without losing its religious power.

Plessner also argues that the structures of the Lebenswelt were strongly influenced by the theology of Luther and that, on this basis, the particularity of the German interiority can be comprehended. Proceeding from the interaction between Lebenswelt and system and the assumption that the Lebenswelt furnishes the system with value, Plessner concludes that the German Lebenswelt cannot furnish political institutions with their necessary value, because their democratic disposition was not understood. With this background, Plessner can take into account the factors that impeded the construction of a democratic societal order.

Plessner’s work suggests that democracy in Germany failed not simply as a result of an economic crisis and a lost war, but instead because the value structures out of which the democracy was constructed, was not sufficiently internalized. The relationship was “play-acted” and not “lived”. I suspect that this is no longer the case, although an abuse of our contemporary normative order in terms of our common democratic values must be plausibly explainable. If this supposition is correct, then there would be an increase in the value of jargon under today’s circumstances, in which non-democratic endeavors would be forced to demonstrate their democratic creed, in order to achieve their antidemocratic ends.

The initial consideration is that Plessner’s arguments about the historical and religious underpinnings of modern society are as valid as ever. Although the social structures that support a democracy and its institutions have moved away from their religious and traditional origins, their effects are still felt. My work starts from the assumption that democratic structures in Germany have taken root and that these structures demand from actors to conceptualize their positions into terms with which they could be justified in the framework of these structures and be understood in the framework of these structures. Nevertheless, Plessner reminds us, that our convictions, even if they take on the form of rational ties to institutions, are still in connection with our past. This connection is marked in a culture-specific way. The historical and cultural traditions of the United States are radically distinct from those of Europe. It is partly owing to these differences that a stable democracy in Germany emerged later than as in the United States.

As Dr. Karp notes in the above, The Belated Nation opens with a quote from Thomas Mann’s speech, given three weeks after the surrender of the Nazis to the Allied forces, Germany and the Germans: “there are not two Germanys, one bad and one good, but instead only one, whose best turned to evil through devilish cunning.” Mann, in a kind of very Christian fashion, rejects the sort of Manichaeist understanding of the problem of Germany, and subsequently Nazi Germany, in favor of the simple one: that Germany turned to evil “through devilish cunning”.

“A New Enlightenment” does not examine this at all, nor mention it, even though it would have been helpful to understanding Germany’s relationship to interiority and subsequently to the Nazis, which are themes Dr. Karp touches on in Aggression in the Lebenswelt. Instead, “A New Enlightenment” focuses entirely on the analysis Dr. Karp makes of Walser. Therefore, before we go into “A New Enlightenment” here, a brief background on Walser, and why he is the subject of Dr. Karp’s dissertation.

“Experiences While Drafting A Soap-box Speech”

Komm auf die Beine, komm her zu mir

(Get up, come here to me)

Es wird bald hell und wir haben nicht ewig Zeit

(It’s almost light and we don’t have much time)

Wenn uns jetzt hier wer erwischt, sind wir für immer vereint

(If they catch us here, we’ll be united forever)

In Beton und Seligkeit

(In concrete and bliss)Hol den Vorschlaghammer

(Grab the sledgehammer)

Sie haben uns ein Denkmal gebaut

(They’ve built us a monument)

Und jeder Vollidiot weiß, dass das die Liebe versaut

(And every fool knows that that screws up love)— Wir sind Helden, “Denkmal” (YT)

Set: On Sunday, October 11, 1998, the renowned German author Martin Walser got up in Paulskirche in Frankfurt, Germany, to accept the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. Then, somewhat hilariously for receiving a prize named after peace, he gave an acceptance speech which can only be described as a political protest of verbal self-immolation which set off months, years really, of discourse. Had Walser given his speech in the Year of Our Lord 2024, there is no doubt he would be trending on X within the hour, with innumerable quote tweets trying to get the perfect dunk or have the hottest take. One can only imagine #MartinWalserHatRecht.

Walser’s speech is so dense, so complex, so interwoven with the German Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung6 that it would be difficult to give it a fair, full treatment here in the context of the discussion of “A New Enlightenment”. For those who are interested, I really recommend listening to the speech (the auto-translate captions available in YouTube into English are very serviceable) to catch Walser’s tone, as well as the audio of the audience reaction at different points through the speech.

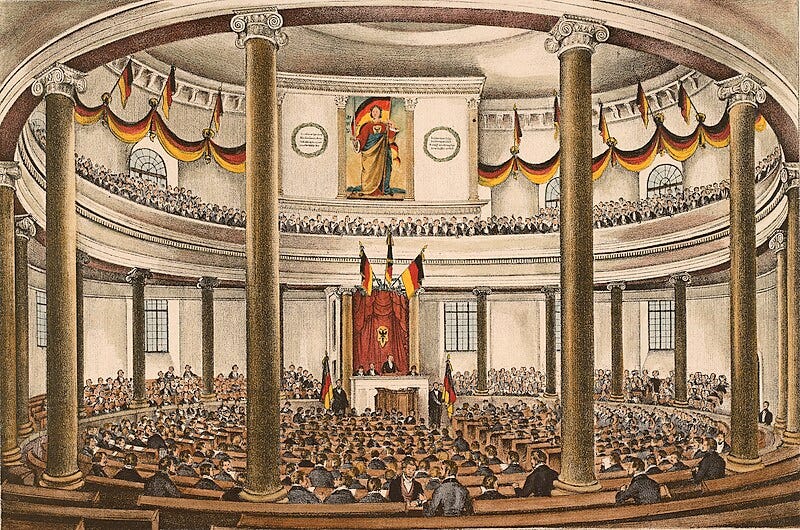

And setting: I do not think it any accident that Walser chose Paulskirche — St. Paul’s Church — for his act of political protest, and I believe the choice of Paulskirche was intended to be read into the context of his speech. The construction of Paulskirche was completed in 1833 for the Lutheran Church, although it was also often used for other “non-religious” gatherings, such as when it became the site of the German unification in 1848.

Walser titled the speech “Erfahrungen beim Verfassen eine Sonntagsrede”, generally translated into English as “Experiences While Composing A Sunday Speech” or “Experiences While Drafting A Soap-Box Speech”. The term Sonntagsrede in German wasn’t familiar to me when I came across it for the first time in Dr. Karp’s dissertation, but from my research, it seems to be somewhat idiomatic, where it is more like a “soap box” or a “political stump speech”, playing off the notion of a “Sunday sermon”, which explains the mixed translations I’ve come across of Walser’s speech title.

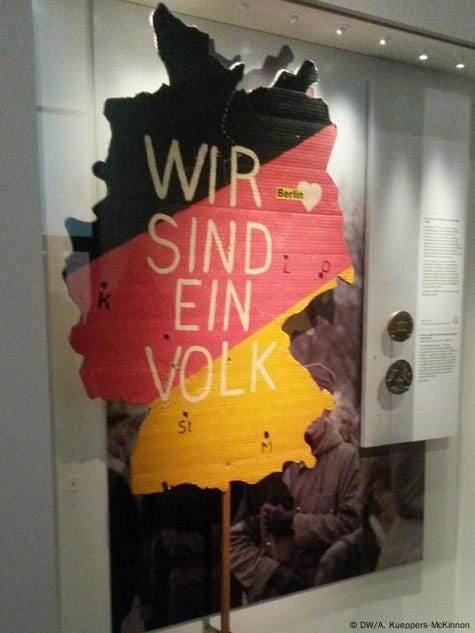

Another material piece of background, perhaps signaled by the choice of Paulskirche, for Walser’s speech is the Wiedervereinigung of Germany, the Reunificiation of East and West Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall on the night of November 9, 1989, almost nine years to the day from Walser’s speech in October 1998. I think it is somewhat difficult from our distance to appreciate the strangeness for the cultural and political development of the people of Germany to have assembled an imperial government, suffered the loss of the First World War, formed a very liberal-libertine Weimar Republic, watch that be seized by this very novel, occult-tinged grand concept of a Third Reich, quickly lost that in a great shame, and then had half the country, including the capital city, literally walled off from the other with completely opposing ideological stances, only to be fused back together again four decades later. To say whiplash of an identity crisis is an understatement.

Much of this, of course, is rooted in the strangeness and newness of the concept of the nation-state as a means for organizing groups of people, but it is undeniable that there is a degree to which the nation-state is a successful enterprise in many cases, and there are certainly rational, fact-based means by which a nation-state can be very roughly carved out. So, to read Walser charitably, his context is the Wiedervereinigung, the construct, the egregore of German nation-state — for which he fought in the Wehrmacht in the Second World War — in the light of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

When Walser gives the speech in October 1998, the country is deep in the throes of discussion and debate about a large-scale Holocaust memorial as the government narrows down its selection of a design for a site that will go right through the heart of Berlin. From a New York Times article ($) in July 1998:

“The real memorials in Germany are the concentration camps,” [Social Democrat leader] Mr. Naumann said in a telephone interview. The projected memorial “will not lead psychologically to what a simple visit to Bergen-Belsen evokes in a more shocking manner.”

Rather, he said, the huge monument [that German Chancellor] Mr. Kohl plans would represent “a memorial for memory, a suspension of guilt in art.” And he accused Mr. Kohl of displaying a ''crude understanding of historical memory, which thinks that things can be finished by a modeled memory, and then you move on in history.”

Mr. Naumann's earlier remarks to German newspaper reporters and broadcasters drew criticism from some Government politicians but also evoked the deep ambiguities -- among German Jews and within political parties -- surrounding one of the most highly charged debates confronting the land a half-century after World War II.

Gerhard Schr[ö]der7, the Social Democratic challenger to Mr. Kohl, said this week that he felt ''very close'' to Mr. Naumann's views. […] Other Social Democrats, however, say the issue should not be part of the election. […] [Mr. Schröder’s support] elicited outrage from some German Jews, sympathy from others and disdain from yet more.

“If this is the great vision of the federal man of culture, and if Mr. Naumann really has no greater concerns, then all I can say is: poor culture,” said Ignatz Bubis, head of the main representative organization of German Jews.

Since the idea of a memorial to honor Holocaust victims was proposed 10 years ago, it has become ever more divisive, drawing objections from politicians and intellectuals that no artistic construction could possibly reflect the enormity of the Holocaust, and that the such a monument would not kindle memory but rather take the place of it.

Nonetheless, Mr. Kohl, who has taken a close personal interest in the project, has insisted that a final choice among four designs would be made before the election, for a ground-breaking ceremony next January -- whoever is Chancellor.

An initial design competition for the memorial was canceled in 1996 and Mr. Kohl ordered a new contest. That produced four finalists, including one design by two Americans, Richard Serra and Peter Eisenmann, which is viewed as the front-runner, even though Mr. Serra left the project in early June.

The American design originally envisaged a huge labyrinth of 4,000 stone pillars of varying heights scattered over 180,000 square feet on a site between the refurbished German Parliament in the Reichstag building and the commercial center under construction at the Potsdamer Platz.

Symbolically, the monument would straddle the former no-man's-land around the Berlin wall and lie directly above or close to some of the landmarks of the Third Reich, including Hitler's bunker.

Construction of the final memorial, a stone’s throw away from the Brandenburger Tor and the Reichstag, would finish in 2004 under the name Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, the “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe”.

Ein Denkmal: a memorial; a monument.

An excerpt of Walser’s speech as translated by Thomas Kovach in The Burden of the Past: Martin Walser and the Modern German Identity:

An equally important literary figure had stated a couple of years earlier: “Go into any restaurant in Salzburg. At first glance you have the impression that these are nothing but fine, upright people. But if you listen in to the conversations of your neighbors at the table, you discover they dream only of genocide and gas chambers.” If you add up what the thinker and the writer – both indeed equally serious – are saying, then the government, the apparatus of state, the party leadership, and the upright people at the next table are all “morally and politically” decadent. […]

It exceeds my moral and political and political imagination, so to speak, to regard what they say as true. Inside me an unprovable suspicion begins to take hold: those who come forward with such statements want to hurt us, because they think we deserve it. Probably they want to hurt themselves as well. But us too. All of us. With one restriction: all Germans. For this much is clear: in no other language in the last quarter of the twentieth century can one speak in such a way about an entire people, an entire population, an entire society. You can only say that about Germans. Or at most, as far as I can see, about Austrians as well. […]

Everyone knows the burden of our history, our everlasting disgrace. There is not a day in which it is not held up before us. Could it be that in doing so the intellectuals who hold it up before us fall prey for a moment to the illusion that, because they have labored once more in the grim service of memory, they have relieved their own guilt somewhat, that they are even for a moment closer to the victims than to the perpetrators? A momentary alleviation of the merciless confrontation of perpetrators and victims. I myself have never felt it possible to escape the side of the accused. Sometimes, when it seems I can’t look anywhere without being attacked by an accusation, I must talk myself into believing, and thereby gaining some relief from the burden, that a routine of accusation has arisen in the media. Easily twenty times I have averted my eyes from the worst filmed sequences of concentration camps. No serious person denies Auschwitz; no person who is still of sound mind quibbles about the horror of Auschwitz; but when this past is held up to me every day in the media, I notice that something in me rebels against this unceasing presentation of our disgrace. […]

In 1977, not far from here in Bergen-Enkheim, I had to give a speech, and I used the occasion back then to make the following confession: “I find it unbearable to make German history end in a product of catastrophe, however bad its recent course has been.” And: “We must grant as little recognition to West Germany, I say, trembling with my boldness, as we do to the East. We must keep open the wound called Germany.” I think of this because once again now I tremble with my own audacity when I say: Auschwitz is not suited to become a routine threat, a means of intimidation or moral bludgeon that can be employed on any occasion, or even a compulsory exercise. All that comes into being through ritualization has the quality of lip service. But what suspicion does one invite when one says that the Germans today are a perfectly normal people, a perfectly ordinary society?

Posterity will be able to read one day, in all the discussions concerning the Holocaust Monument in Berlin, what people stirred up when they felt themselves responsible for the conscience of others: paving over the center of our capital to create a nightmare the size of a football field. The monumentalization of our disgrace. The historian Heinrich August Winkler calls this “negative nationalism.” I dare to assert that this is not a bit better than its opposite, even if it appears a thousand times better. Probably there is a banality of the good too. […]

When a thinker criticizes “the full extent of the moral and political degradation” of our government, apparatus of state, and party leaderships, then the impression cannot be avoided that he considers his conscience clearer than those of these morally and politically decadent souls. But what does that really feel like – a purer, a clearer, an immaculate conscience? To protect myself from further embarrassing questions, I will call to my aid two intellectual giants whose understanding of language is beyond question: Heidegger and Hegel. Heidegger in his 1927 work Being and Time: “Becoming certain of not having done something does not possess the character of a phenomenon of conscience. On the contrary: this becoming certain of not having done something can sooner mean a forgetting of conscience.” That is, put less precisely: a clear conscience is as perceptible as the lack of a headache. But then it is said in the paragraph of Being and Time about conscience: “Being guilty is part of being itself.” I hope that this won’t once again be understood right away as a convenient phrase for letting off the hook those contemporary obscurantists who don’t want to feel guilty. And now Hegel. Hegel writes in his Philosophy of Right: “Conscience, that deepest inward solitude within oneself, where all that is external and all that is limited disappears, this thoroughgoing withdrawal into oneself.”

In the opening paragraphs to Dr. Karp’s dissertation, he explains how he came to the choice to analyze the Walser speech:

This work began with the observation that some statements have a drive-relieving2 effect, and not despite, but because of their obvious irrationality. Statements that are obviously self-contradictory offer to a person the opportunity to formally commit to the normative order of their cultural environment, and, at the same time, to express taboo desires3 that violate the rules of this order. As a result, neither cultural nor social sanctions are triggered. On the contrary: such statements solidify an integration process by making the cost of integration psychologically bearable. Borrowing from Adorno, I name such statements “jargon”. […]

As a text alone, the Paulskirche speech by Martin Walser would not have been suitable for analysis in this frame: taken word for word, it becomes difficult to craft a serious argument with this speech: Walser’s claim that he has been forced to constantly bear the gruesome events of mass slaughter is simply false. But with the background of Adorno’s narrative of the functional role of jargon, Walser’s speech now comes to merit a completely different standing. For the arguments are no longer examined alone on whether they are true and therefore valid, but rather whether they have an effect and how this effect can be set in relationship to the truthfulness of the argumentation. Walser’s impression that he is to be haunted by the Holocaust and by the representatives of a “gruesome remembrance service” is devoid of any basis, but the cultural significance of his speech is not. It was enormous. For what reason, Adorno can help us understand.

The broad overarching goal, then, of Dr. Karp’s dissertation is for Dr. Karp to analyze, demonstratively to earn his doctorate, how Adorno’s concept of jargon as laid out in Jargon der Eigentlichkeit (The Jargon of Authenticity), alongside concepts from several other thinkers, can be applied to the Walser speech.

Dr. Karp explains:

For Adorno, jargon is communication that takes into account particular needs that arise through seemingly unsolvable conflicts in the culture. Instead of exposing the origins of the cultural misery as a law and demanding real change, they are portrayed as a constant of human existence. Socially coercive circumstances look like forces of nature which threaten to crush people if they ever “get in the way”. The cultural power of jargon consists of its double function. In one function, it enables, at the level of action, the consideration of those constraints that have become objective, which are applied on the people, and so serves as an adaptation strategy. In the other function, it simultaneously expands the sphere of action in which actors can operate without regard to the generally accepted normative rules. So, these needs can be satisfied that would otherwise be sublimated or acted out.

It could be shown that, behind Adorno’s “official” approach, another approach remains hidden, one that moves away from premises that are exclusively based on coercion: namely, an explanation for the positive attitudes of the perpetrators toward their culpability. This is the only way Adorno can navigate through a criticism of the falsity of the post-war German society, which obscured its own guilt through jargon.57

And:

Authenticity is a carrier of political ideology. Its political meaning is not so much the effect of its construction, which traces back to a certain philosophical tradition (Heidegger in particular). […] The “becoming real” of this idea can only be carried out in society. It therefore had to accord with needs that arise either out of societal conditions or out of the interaction of individual needs and societal conditions. These societal conditions form the background before which authenticity can fraternize with jargon. The force of authenticity is fed by the tension that emerges from such societal circumstances. The underlying assumption is that this tension, which it incidentally also encourages, cannot be lifted through a change of societal circumstances. Their societal origin must therefore be denied. Through this denial, that which is horrifying about society is legitimately supported.66

Die Zeit’s “A New Enlightenment”

“A New Enlightenment” situates itself with reference to the recently-released German-language documentary Watching You: Die Welt von Palantir und Alex Karp.8 (I use the term “documentary” loosely; as far as I can tell from trailer footage, it appears the film crew followed Dr. Karp in public quite a bit.) Dr. Neumann opens with a description of a photo shown in the film, taken in Frankfurt in 1997, with the then-doctoral student Karp standing in a large group of people celebrating the 80th birthday of the psychoanalyst Margarete Mitscherlich.9 According to Dr. Neumann, Karp “looks shy, almost untouchable”.

“A New Enlightenment” continues (my translation):

Why is one of the most influential big-data businessmen standing among the greats of the Frankfurt School? And how can it be that Karp, who still today describes himself as a leftist, as a “Neo-Marxist”, founds a company in 2003, just six years after the birthday party in Frankfurt, that is forcing its way to the top of data capitalism with its surveillance-state fantasies?

[…]

In spite of his enormous success, Karp remained a figure in the background, hidden from view, from the critical questions. What drives the 56-year-old? What are his motives? On this, there has been much speculation, but seldom was Karp’s academic background ever examined. His dissertation from Frankfurt, titled Aggression in der Lebenswelt, was occasionally cited here and there. Yet, it may hold a key to his thinking. For it is in the Frankfurt years, in the ideas of the German Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung, in which Karp’s Big-Data philosophy is established. One must only zoom in once.

Karp is concerned with repressed guilt. He grew up in Philadelphia, his father is Jewish, his mother African-American — and he has German roots. Karp goes to study law at Stanford University, which is regarded as the elite training grounds of Silicon Valley. But there is something from his own past he cannot let go of. He is interested in German thought, Hegel, Marx, and critical theory — and the Frankfurt School. […] Soon [after his studies in Germany] he is away again, back in the States, to found Palantir with his friend from the Stanford days, Peter Thiel. But the thinking of the Frankfurt School, of Adorno and company, is not far away, it is working in him.

In 2002, his dissertation is published: it is an examination of the question of how violence comes in the modern world and increases from there to its most extreme. And, surprisingly, his dissertation does not concern itself with the silence after the war, but instead with a case out of Karp’s own time in Frankfurt: it is about the Martin Walser speech at Paulskirche in 1998, in which he spoke of the “moral cudgel of Auschwitz”, because he had enough of the German guilt and found that a forced remembrance had developed which his conscience, his own will, had refused to be subjugated to. Karp follows Walser: “Walser’s impression that he is to be haunted by the Holocaust and by the representatives of a “gruesome remembrance service is devoid of any basis, but the cultural significance of his speech is not. It was enormous.”

Now, one would expect that the doctoral student Karp would react to Walser as a leftist critic of ideology. But Karp remains neutral. The moral judgment does not interest him as much as the algorithm of aggression.10

With reference to his own conscience, Walser spoke to the hearts of many; only Ignatz Bubis, then the Chairman for the Central Council of Jews in Germany, remained sitting and silent in the applause of Paulskirche.11 What fascinated Karp so much about the event was the ways and means in which Walser presents the “intellectuals” as a scapegoat to whom the guilt for our own misfortune could be ascribed.

The intellectuals were supposed to be the ones who constantly threatened us with the moral cudgel and who were responsible for the false ritualization of the Holocaust remembrance. Here, it becomes apparent to Karp, how the drive-relief functions: through aggression. It was a means of integration, in democracies too. One gathers a group around himself by excluding others from it. Walser was the best example: “The meaning of his speech is owing to the fact that it was framed in understandable democratic concepts, while it simultaneously excluded a particular group or chosen individuals from the rights that this tradition provides.”

Could it be, that for Karp, Walser evinces the power of unfiltered aggression, which only waits for the right moment to ignite? Although Karp never voiced what his dissertation about the German Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung had to do with his Big Data thinking, one may assume that it is exactly here, in this alarm, that lay the basis for expanding the rational conception of man into a critical component: one had to penetrate into the hidden inner room, in all the dirty corners of the private life, in order to bring irrational drives under control. The German struggle with the Nazi past had shown that the violence was never far away; instead, it had only lain dormant. […] Walser had spoken out of the deepest depths of his conscience, he had given into his aggression. And so one has to literally get up close and personal with the subjects in order to monitor their dark souls.

If Walser thought he was addressing taboos that should have never emerged, then one could say the same of those secrets that should have never have remained hidden. And what better way to penetrate into these mysteries than with the volumes of data from the Internet, which could also be quietly collected away from the public eye?

Then, when September 11th came, and the Twin Towers in New York collapsed, the symbols of the rational, Western world, matters became clear for Karp: one only needed to train machines, artificial intelligences well enough, supply them with data from all possible areas, from politics, the military, the clandestine services, and then later social media, one had only to venture far enough into these hidden chambers, in these deep dark caves of the human Lebenswelt, to illuminate it, preventatively.

Morality and stale criticism of ideology did not get us anywhere. […] For Karp, it was now a matter of learning the jargon of violence, of mastering it, in order to preempt another attack. But it was imperative to do this in secret and exude optimism to the outside world, so as to not endanger the order that must be preserved. There, in Frankfurt, Karp had penned the scarcely 130 pages12 in his dissertation a script with which the liberal project of the West should now be altered: the aim was now no longer the classical Enlightenment, the ideals of freedom and equality, but instead about counterintelligence. Espionage was in the hands of a few. It was a fight — on the outside, against terror, and on the inside, against the leftist do-gooders who hadn’t understood the seriousness of the situation. […]

Karp, student of the Frankfurt School, has made no secret of the dangers of his software — of its terrible destructive force. “Our product is occasionally used to kill people,” Karp says at one point in the documentary. “All types of targets” are among them. In a world where everyone fights among each other, the only solution is to be faster. Unless you play God a little bit and, with large quantities of data, foretell the future.

Die Frage der Walsers Wahrhafigkeit

“A New Enlightenment” does not at all question Walser’s claim in his speech that he must experience the guilt and the shame of the Holocaust and Nazi Germany alone, in his conscience. Dr. Karp, however, does, at least as I read him. He seems to believe that there is at least a possibility that Walser is using the shared cultural background of the Lutheran appeal to the interiority of the conscience only as jargon to communicate a socially-held belief — not a private one. Dr. Karp might assert that Dr. Neumann seems to fall prey to the very jargon that he is attempting to expose.

In his dissertation, Dr. Karp argues that, borrowing from Adorno, the drives are “not repressed” and the source is “social”:

What is peculiar is that in Adorno’s “The Jargon of Authenticity” these urging feelings are largely conscious and at the most pre-conscious. In other words, Adorno’s needs are instinctual drives, although not drives in the Freudian sense. They are not repressed. In fact, they cannot be spoken of as an unconscious process.

So its source is “social”.97 […] Plainly assuming the perversion of human needs as such replaces the concept of cultural action with an ontological concept of human needs. Therefore, I have translated Adorno’s description of such needs into the conceptual terms of this approach in order to be able to capture the sociological content of his statements in the terms of my own approach.

Dr. Karp continues:

Meanwhile, the question as to whether Walser’s speech is fashioned to provide an outlet for an aggressive attitude and posture of the public remains unanswered. […] Walser appeals to a religious tradition that Plessner summarized under the name “worldly piety”. The religious-sociological background of Walser’s critique is self-evident to the listeners. It is exactly this self-evidentness that permits Walser to present his approach as universal. His premises therefore need neither be substantiated nor critically examined. They need only mere reference.98 […]

Walser becomes a Protestant. The doctrine: Rid yourself as much as possible of your cultural environment and its historical background. Be an individual, no simple member of a whole. […] The culturally legitimate background of Walser’s statements is of enormous significance, not only because it alone empowers Walser to condemn the current engagement with the Holocaust in such a way, but also because claims taken as self-evident are examined for their validity against this background. It is the interplay of cultural legitimacy with taboo statements, but which would be perceived by most as self-evident and therefore correct, that ensures the cultural effectiveness of these claims. […]

Martin Walser’s speech gives the impression that he has little interest in influencing the opinions of the listeners through persuasion. He forgoes the usual demonstration of new points of view.91 It would be superfluous in any case. Instead, he preaches to the choir. His speech is to help the listener stand by his opinion. […] Walser’s project is therefore effective because his interpretation of reality corresponds to the perception of most of his listeners. […] Under these conditions can the enlightened democrat demand his rights and knock the trouble-makers — like Bubis — back to their deserved place. In this frame, it concerns the position of the victim in the present; whether one can stand it as a constituent part of contemporary life, or whether the irritation of the shame that he represents is too much. (emphasis added)

Interestingly, there is a reading of “A New Enlightenment” in which Dr. Neumann may actually be steelmanning Walser’s perspective on the aloneness of the conscience as he never questions it, nor ever agrees with Dr. Karp that it should be questioned. Instead, “A New Enlightenment” employs in its discussion about Palantir — but really about Dr. Karp — strong language about violation, about the hiding of secrets, language that itself never appears in Dr. Karp’s dissertation: that one has to “penetrate” into hidden inner rooms, the “dirty corners of the private life”, and that one must “literally get up close and personal” with subjects to monitor their “dark souls”.13 But, in so doing, Dr. Neumann assumes the exact same religious-influenced, self-evident frame that Walser is calling to in order to re-normalize aggression socially, and the entire purpose of the religiously-toned language is to act as a jargon for aggression, not to assert it on its own merits.

Who Is The Stranger To Us?14

You drift through the years

And life seems tame

'Til one dream appears

And Love is its name

And love is a stranger

Who'll beckon you on

Don't think of the danger

Or the stranger is goneThis dream is for you

So pay the price

Make one dream come true

You only live twice— John Barry & Nancy Sinatra, “You Only Live Twice” (YT)

The stranger is such an important idea I cannot at all do it justice here, but it is always worth exploring and situating if possible, especially given the tone in “A New Enlightenment” toward Dr. Karp. “A New Enlightenment” opens up with describing the photo of Dr. Karp at the birthday party in 1997 as someone who looks “scheu” (shy), “beinahe unberührbar” (almost untouchable). Dr. Karp has described himself many times as having a tendency to shyness and introversion (here, very recently, “I am an introvert”) but “beinahe unberührbar” is such an interesting choice of descriptor.15 For one, I am pretty sure I know the photo in question, and all I see is someone smiling in a birthday photo as you do. To be sure, the smile is more on the shy side than the grinning, exuberant side, but there is nothing out of the ordinary otherwise and it is so well within the range of normal human expression for a birthday photo. Zurückhaltend, guarded, reserved, would have made sense, and maybe one I might have used, but “beinahe unberührbar”? Almost untouchable?

While it doesn’t make much sense as a descriptor of Dr. Karp in the photo, “almost untouchable” does make sense as a descriptor of the author’s relationship to him, because “almost untouchable” is the relationship that every one of us has to every stranger in our midst, and, while I have not a clue as to whether there is any sort of backstory or prehistory or personal relationship between Drs. Karp and Neumann, it is indisputable in my view that Dr. Karp still represents the stranger in relationship to Dr. Neumann.

Interestingly, Dr. Karp explores the concept of the stranger in his dissertation in order to set up Walser’s relationship to the stranger:

The irritation that the stranger calls forth in others cannot exclusively be traced back to his presence, but rather it must be to those actions and viewpoints that make possible his role in the society to begin with. In the society the stranger creates strange things out of all that he touches. He imports ideas that apparently did not exist before and did not need to exist. For his contribution to society, the stranger cannot hope for recognition and reward. The contempt for the stranger, according to Baumann, stems from two reasons: because the stranger came without invitation, and second, because he has even come at all. (emphasis added)

“A New Enlightenment” frames Dr. Karp as the stranger from the start, describing his mixed insider-outsider status, as a man who “grew up in Philadelphia” with a Jewish father and an African-American mother, but noting that “he has German roots” and “there is something from his own past he cannot let go of”. “A New Enlightenment” goes on to describe that, after Dr. Karp studies in Frankfurt, he leaves to go back to the States, even as “the thinking of the Frankfurt School, of Adorno and company, is not far away, it is working in him.”

Then, in the article’s telling, Karp comes to Germany, studies under the Frankfurt School, and then leaves again to the U.S. to start a data company after completing his dissertation on Walser in which he realized that:

Walser had spoken out of the deepest depths of his conscience, he had given into his aggression. And so one has to literally get up close and personal with the subjects in order to monitor their dark souls.

“A New Enlightenment” suggests that Dr. Karp, having been a stranger who integrated at least somewhat into Germany and then left, now wants to “monitor their dark souls” — i.e., the souls of Germans like Walser, and perhaps even for Germans like Dr. Neumann, for any "latent “aggression” in the “deepest depths of [the] conscience”.

I would suggest, however, that such a framing is much less about an actual description of Dr. Karp’s own goals for Palantir — we will discuss more on that below — but is much more about understanding, in the author’s view, Dr. Karp as a bringer of some sort of judgment, not because of his actual actions and goals around Palantir, but solely because he is a stranger.

The stranger is always fearsome, ultimately, because the stranger comes from outside the community and represents a judgment of the community, for he is not socialized and enculturated into a community, but rather he arrives to the community as he finds it. Dr. Karp is very much seen in this piece as someone with a unique insider-outsider bias, someone who has a mixed-race background, Jewish, American but learns German, who then visits and leaves again with the thinking of Germany still within him, suggesting that he is still inhabiting the role of the stranger to Germany even outside of it. This is particularly interesting as, elsewhere in “A New Enlightenment”, Germany’s reticence toward Palantir as a product is highlighted, as Dr. Neumann reminds the audience of the Interior Minister Nancy Faeser’s recent nationwide ban on using Palantir, citing concerns about data protection (although some within the German government have since rethought this stance) . Palantir responded to Minister Faeser in “At the Expense of Security”, and Amit in Daily Palantir charitably gives Germany the benefit of the doubt:

The irony of Germany's stance on Palantir, given both entities' emphasis on data privacy, is what makes this so frustrating. Germany has a well-documented sensitivity to matters of personal information security and surveillance, which can be traced back to its experiences with state surveillance during the Nazi era and the Stasi in East Germany. This historical backdrop has shaped a national ethos that fiercely protects individual privacy rights.

Palantir, however, was founded with the vision of protecting people's fundamental rights while enabling institutions to effectively analyze large volumes of data. The company asserts that it designs its products with privacy and civil liberties in mind. Palantir’s platforms are built to help organizations integrate their data without compromising security or privacy; they have implemented various features aimed at ensuring users can control access to sensitive information.

However, despite Palantir's professed commitment to data protection principles, there remains skepticism among German officials and public alike regarding the application of these principles in practice. Concerns persist about whether software from an American company like Palantir could become a tool for excessive surveillance or could be misused beyond its intended scope—especially given past revelations about U.S.-based technology companies' involvement in mass data collection activities.

But one wonders if it is something else beyond a supposed concern about data privacy, which could very well be the same tone that is highlighted in “A New Enlightenment”. Dr. Karp’s very particular relationship to Germany — a half-German Jew raised in America who learns the language and moves within the culture of Germany and among her people only to leave again — may be the exact but unstated reason for the German discomfort with Palantir, because he, to them, is the almost-untouchable-stranger.

Because of the judgment that the stranger represents to the community that will not fully accept him as one of their own, and the subsequent fear he engenders, he becomes, in the eyes of the community, like God, a being so powerful he is not only willing but capable of “monitoring [the] dark souls” of the community for their sins. “A New Enlightenment” ends by reminding the reader again that Dr. Karp is one of us Germans reading in Die Zeit, a “student of the Frankfurt School”, who has a product with “terrible destructive force” that has been “occasionally used to kill people” — that is, a product, like God, capable of rendering judgment. Indeed, even in the clean, modern, secular pages of Die Zeit, Dr. Neumann’s last lines to the reader invoke the no one less than the Almighty Himself:

Karp, student of the Frankfurt School, has made no secret of the dangers of his software — of its terrible destructive force. “Our product is occasionally used to kill people,” Karp says at one point in the documentary. “All types of targets” are among them. In a world where everyone fights among each other, the only solution is to be faster. Unless you play God a little bit and, with large quantities of data, foretell the future.

Dr. Karp in Aggression in the Lebenswelt:

Adorno sees in the pseudo-sacral imagery the vestiges of a framed value-system already in question, which served people to lend to their statements an appearance of validity. This is intended to enable the persistence of such magical thought that still stirs people as ever. The latter is the language, that “with primal pleasure forces the hearts of all hearers” (Goethe: Faust). One seals oneself off against religious arguments, because, strictly speaking, one recognizes their absurdity, and still one uses them, because they achieve something.81 The contradiction of a language constructed with the help of religious imagery, that simultaneously obscures its sacred origin, paves the way for the marginalization introduced by jargon to follow.

Macht Arbeit “Frei”?

Today, mere self-preservation forces all of us to look at the world anew, to think strange new thoughts, and thereby to awaken from that very long and profitable period of intellectual slumber and amnesia that is so misleadingly called the Enlightenment.

— Peter Thiel, “The Straussian Moment” (Politics & Apocalypse)

WAGNER: But the great world! the heart of mind of man!

We all seek what enlightenment we can.

FAUST: Ah yes, we say ‘enlightenment’, forsooth!

Which of us dares to call things by their names?

Those few who had some knowledge of the truth,

Whose full heart’s rashness drove them to disclose

Their passion and vision to the mob, all those

Died nailed to crosses or consigned to flames.— Faust

Of course knowing the op-ed was about Dr. Karp, when I first looked at the title, I thought surely it was intended to be a reference to the famous book Dialectic of Enlightenment by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, but no such reference came. I was struggling to tell if the author was even familiar with it, but discussion on it would have been extremely helpful to his analysis, so we will supplement here. In Dr. Neumann’s view, Dr. Karp’s dissertation is a “script with which the liberal project of the West should now be altered: the aim was now no longer the classical Enlightenment, the ideals of freedom and equality” but “counterintelligence” which is become a fight “on the outside, against terror, and on the inside, against the leftist do-gooders”.

In this thin argument, “A New Enlightenment” accepts prima facie the very same reification of ideas that Adorno criticizes in Dialectic of Enlightenment by defining the Enlightenment in these terms like “freedom” and “equality”, presupposing in its tone that the Enlightenment, the project of modernity itself, is an unequivocal good, and suggests that Dr. Karp would be committing a kind of wrong to even question it, as that would be going against the ideas of “freedom” and “equality”.

To assume, however, that the Enlightenment is an unequivocal good is a perspective that is already on the wrong side of history. As Zygmunt Bauman argues in Modernity and the Holocaust:

The unspoken terror permeating our collective memory of the Holocaust (and more than contingently related to the overwhelming desire not to look the memory in its face) is the gnawing suspicion that the Holocaust could be more than an aberration, more than a deviation from an otherwise straight path of progress, more than a cancerous growth on the otherwise healthy body of the civilized society; that, in short, the Holocaust was not an antithesis of modern civilization and everything (or so we like to think) it stands for. We suspect (even if we refuse to admit it) that the Holocaust could merely have uncovered another face of the same modern society whose other, more familiar, face we so admire. And that the two faces are perfectly comfortably attached to the same body. What we perhaps fear most, is that each of the two faces can no more exist without the other than can the two sides of a coin. […]

The etiological myth deeply entrenched in the self-consciousness of our Western society is the morally elevating story of humanity emerging from pre-social barbarity. […] By and large, lay opinion resents all challenge to the myth. Its resistance is backed, moreover, by a broad coalition of respectable learned opinions which contains such powerful authorities as the 'Whig view' of history as the victorious struggle between reason and superstition; Weber's vision of rationalization as a movement toward achieving more for less effort; psychoanalytical promise to debunk, prise off and tame the animal in man; Marx's grand prophecy of life and history coming under full control of the human species once it is freed from the presently debilitating parochialities; Elias's portrayal of recent history as that of eliminating violence from daily life; and, above all, the chorus of experts who assure us that human problems are matters of wrong policies, and that right policies mean elimination of problems. Behind the alliance stands fast the modern 'gardening' state, viewing the society it rules as an object of designing, cultivating and weed-poisoning.

In view of this myth, long ago ossified into the common sense of our era, the Holocaust can only be understood as the failure of civilization (i.e. of human purposive, reason-guided activity) to contain the morbid natural predilections of whatever has been left of nature in man. Obviously, the Hobbesian world has not been fully chained, the Hobbesian problem has not been fully resolved. In other words, we do not have as yet enough civilization. The unfinished civilizing process is yet to be brought to its conclusion. If the lesson of mass murder does teach us anything it is that the prevention of similar hiccups of barbarism evidently requires still more civilizing efforts. [….]

The Hobbesian world of the Holocaust did not surface from its too-shallow grave, resurrected by the tumult of irrational emotions. It arrived (in a formidable shape Hobbes would certainly disown) in a factory-produced vehicle, wielding weapons only the most advanced science could supply, and following an itinerary designed by scientifically managed organization. Modern civilization was not the Holocaust's sufficient condition; it was, however, most certainly its necessary condition. Without it, the Holocaust would be unthinkable. It was the rational world of modern civilization that made the Holocaust thinkable. “The Nazi mass murder of the European Jewry was not only the technological achievement of an industrial society, but also the organizational achievement of a bureaucratic society.” [...]

At no point of its long and tortuous execution did the Holocaust come in conflict with the principles of rationality. The 'Final Solution' did not clash at any stage with the rational pursuit of efficient, optimal goal-implementation. On the contrary, it arose out of a genuinely rational concern, and it was generated by bureaucracy true to its form and purpose. […] The Holocaust was not an irrational outflow of the not-yet-fully-eradicated residues of pre-modern barbarity. It was a legitimate resident in the house of modernity; indeed, one who would not be at home in any other house. […]

Yet there is also another message [suggested by Eichmann’s defense in Jerusalem16], not so evident, though no less cynical and much more alarming: Eichmann did nothing essentially different from things done by those on the side of the winners. Actions have no intrinsic moral value. Neither are they immanently immoral. Moral evaluation is something external to the action itself, decided by criteria other than those that guide and shape the action itself. (emphasis added)

As Karl Marx said, the modern world is not nearly as fixed as it supposes itself to be, and tell us who live within it that it is, but rather is something quite the opposite, a place where “all that is solid melts into air”:

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

— Manifesto of the Communist Party (tr. Samuel Moore and Friedrich Engels)

Dr. Karp himself briefly references Dialectic of the Enlightenment in his dissertation17:

The project of the Enlightenment, according to Adorno, has subjected people to a “dispositional thinking” and committed people to a “self-preservation through adaptation”. It is therefore ludicrous to associate the Enlightenment with progress. Such a picture of the Enlightenment misjudges the reality of human history, for the “fully enlightened earth radiates under the banner of triumphant calamity”.77

Adorno’s arguments about the modern reification of ideas are aptly summed up in this simple example from The Jargon of Authenticity (tr. Edmund Jephcott)18:

Gottfried Keller, the lyricist, on whom the apostles of harmony looked down condescendingly, wrote a poem called “Encounter,” a poem of wonderful clumsiness. The poet unexpectedly meets, in the woods, her

whom alone my heart longs for,

wrapped whitely in scarf and hat,

transformed by a golden shine.

She was alone; yet I greeted her

hardly made shy in passing on,

because I had never seen her so

noble, still, and beautiful.The misty light is that of sadness, and from it the word “encounter” receives its power. But this sadness gathers to itself the feeling of departure, which is powerful and incapable of unmediated expression; it designates nothing other than, quite literally, the fact that the two people met each other without any intention. What the jargon has accomplished with the word “encounter,” and what can never again be repaired, does more harm to Keller’s poem than a factory ever did to a landscape. “Encounter” is alienated from its literal content and is practically made usable through the idealizing of that content. There are scarcely encounters like Keller’s any longer — at the most there are appointments made by telephone. (emphasis added)

In Dialectic of Enlightenment:

In the authority of universal concept the Enlightenment detected a fear of the demons through whose effigies human beings had tried to influence nature in magic rituals. From now on matter was finally to be controlled without the illusion of immanent powers or hidden properties. For enlightenment, anything which does not conform to the standard of calculability and utility must be viewed with suspicion. Once the movement is able to develop unhampered by external oppression, there is no holding it back. Its own ideas of human rights then fare no better than the older universals. Any intellectual resistance it encounters merely increases its strength. The reason is that enlightenment also recognizes itself in the old myths. No matter which myths are invoked against it, by being used as arguments they are made to acknowledge the very principle of corrosive rationality of which enlightenment stands accused. Enlightenment is totalitarian. […]

Enlightenment is mythical fear radicalized. The pure immanence of positivism, its ultimate product, is nothing other than a form of universal taboo. Nothing is allowed to remain outside, since the mere idea of the “outside” is the real source of fear. If the revenge of primitive people for a murder committed on a member of their family could sometimes be assuaged by admitting the murderer into that family, both the murder and its remedy mean the absorption of alien blood into one’s own, the establishment of immanence. […] All birth is paid for with death, all fortune with misfortune. While men and gods may attempt in their short span to assess their fates by a measure other than blind destiny, existence triumphs over them in the end. Even their justice, wrested from calamity, bears its features; it corresponds to the way in which human beings, primitives no less than Greeks and barbarians, looked upon their world from within a society of oppression and poverty. Hence, for both mythical and enlightened justice, guilt and atonement, happiness and misfortune, are seen as two sides of an equation. Justice gives way to law. The shaman words off a danger with its likeness. […] The step from chaos to civilization, in which natural conditions exert their power no longer directly but through the consciousness of human beings, changed nothing in the principle of equivalence. Indeed, human beings atoned for this very step by worshipping that to which previously, like all other creatures, they had been merely subjected. Earlier, fetishes had been subject to the law of equivalence. Now equivalence itself becomes a fetish. The blindfold over the eyes of Justia means not only that justice brooks no interference but that it does not originate in freedom. (emphasis added)

The quintessential image of the Holocaust as a very modern project caught up in the reification of ideas is in Dachau, a small German town just north of Munich, where the first concentration camp of the N.S. Staat was built in 1933, and would become the model for all the others. At the gates of Dachau, inscribed in iron in a modern font is the phrase “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” — translated literally, “work makes free” or more liberally, “work sets you free”.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum explains the kind of “freedom” that the captives of Dachau experienced behind its iron gate:

[M]ass executions by shooting took place, first in the bunker courtyard and later in a specially designed SS shooting range. Thousands of Dachau prisoners were murdered there, including at least 4,000 Soviet prisoners of war following the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. […]

Physicians and scientists from the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) and the German Experimental Institute for Aviation conducted high-altitude and hypothermia experiments, as well as experiments to test methods for making seawater potable. […] German scientists also carried out experiments to test the efficacy of pharmaceuticals against diseases like malaria and tuberculosis. Hundreds of prisoners died or were harmed as a result of these experiments. […] Dachau alone had some 140 subcamps, mainly in southern Bavaria where prisoners worked almost exclusively in armaments works. Thousands of prisoners were worked to death.[…]

As Allied units approached [in the liberation of Germany], at least 25,000 prisoners from the Dachau camp system were force marched south or transported away from the camps in freight trains. During these so-called death marches, the Germans shot anyone who could no longer continue; many also died of starvation, hypothermia, or exhaustion.

On April 29, 1945, American forces liberated Dachau. As they neared the camp, they found more than 30 railroad cars filled with bodies brought to Dachau, all in an advanced state of decomposition. […] The number of prisoners incarcerated in Dachau between 1933 and 1945 exceeded 200,000. It is difficult to estimate the number of prisoners who died at Dachau. The thousands brought to the camp for execution were not registered before their deaths. Furthermore, the number of deaths that occurred during evacuation have not been assessed. Scholars believe that at least 40,000 prisoners died at Dachau.

It is little wonder that the entire tone of Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, written in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, is completely blackpilled about the Enlightenment project that is so attached to “ideas” of “freedom” and “equality” while being cut off from the actual experience of it, and allows for seemingly schizophrenic projects like Nazism to flourish. As Adorno poetically writes in The Jargon of Authenticity, “Language mythology and reification become mixed with that element which identifies language as antimythological and rational.”

Earlier this year, Dr. Karp seemed to almost prophetically anticipate and respond to the criticisms of him in “A New Enlightenment”, which was published a few months after these remarks:

Often, people who are allergic to technical issues are actually the adversaries of the Enlightenment, because if your enterprise doesn’t work, your country doesn’t work, and nothing can work, and mostly because you’re so lazy you’re not willing to take the time to go figure out how these issues are solved technically, or you’re so arrogant that you don’t believe you have to understand these issues, you’re actually — the person yelling at me: you should be yelling at yourself. We’re on the side of Enlightenment. Laziness, ineptitude, and watching your society go over the edge is not the friend of your enterprise, your country, [or] the betterment of human rights.

And Dr. Karp in impassioned comments at the World Governments Summit in 2024:

You have to fix actual problems. Democracy is not an excuse for having nothing that works! If it does not work, nobody is going to buy into it! One of the most important things we have to push back on is “Oh, it can’t work, because we have these five things that don’t work…”

Nobody has time for that. We are in very dangerous times. Every part of the society has to work. How do you define “working”? I put in a dollar, I get more than a dollar out. That’s “working”.

The people who purvey that massively underestimate the intelligence of the people they’re talking to. People have no time for that. […] “We invest lots and nothing happened; we invest more and nothing happens.” It’s not the input; it’s the output. We need a relentless focus on that across the world. And that is the only thing that will stabilize your society. Everything else just malfunctions, misfunctions, corrodes your society, and produces the worse people ever, because the people who use to advance themselves understand that it doesn’t work and understand that they can manipulate people like that. It has to be fought against at every element.”

Palantir Against The Panopticon19

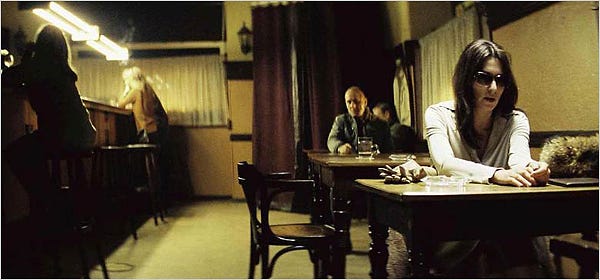

When I first began reading about Dr. Karp in July of last year, I came across a very well-written article from 2020 — for which Mr. Thiel and Dr. Karp actually went on the record, which is saying something — in the New York Times Magazine: “Does Palantir See Too Much?” Not knowing all that much about Dr. Karp at this point, this photograph accompanying the article immediately seized my attention:

The picture on the wall, looking over Dr. Karp and the Palantirians like an icon of a Catholic saint, is of the French philosopher Michel Foucault. I have long regarded Foucault as someone so leftist-minded that I honestly never would have imagined myself reading him, but as I was reading and thinking for this post, I realized that Foucault’s magisterial work Discipline and Punish may be one of the most essential puzzle pieces to understanding how Dr. Karp thinks about Palantir, specifically, the third part of the book, “Panopticon”.