Author’s Note: This post revisits and expands upon some themes I first raised in a viral Amazon.com review of a 2021 biography of Peter Thiel. Marginal Revolution: “Christian review of Peter Thiel.” Some amusing Twitter traffic on my review here. While my review is in-depth and touches on Mr. Thiel’s interest in Girard and apocalyptic themes, it was structured as more of a defense of Mr. Thiel against his depiction in the biography, and I drafted the following to provide a more affirmative, global defense of Mr. Thiel’s thought and philosophy, including an explanation of how he forever altered my own perspective.

I can’t recall how I became aware of Peter Thiel; it’s most likely I encountered him first in the pages of the Wall Street Journal where he had some coverage during the PayPal years of the early 2000s. I remained mildly interested enough in his libertarian, futuristic thought that I saw him on his 2014 Zero to One book tour, although I wasn’t invested enough to buy a copy of the book at that time, even to have it signed at the signing thereafter. In that talk, though, he mentioned a professor of his named René Girard, a man I’d never heard of, so the next day I dutifully read all of what was available on Google Books of Dr. Girard’s I See Satan Fall Like Lightning.

As someone who’s almost always circled around Christianity, both intellectually and in personal practice, what I read of I See Satan Fall stuck in my craw. I didn’t understand or even see the entire Girardian framework at that time, but I knew that there was something there, enough so that it was still lingering in my mind even a few months later when I discussed some of the premises of the book at a dinner with friends.

I became distracted by life, though, and it was seven years later, when, on a lark in a middle of a global pandemic, I decided to start investigating Mr. Thiel and understanding his thought in more depth. As I was both highly anxious because of the pandemic, and mentally understimulated as a result of spending 22 hours a day in my studio apartment for untold months on end, I came to find filling my headphones with Mr. Thiel’s monotonous, unexciting tone of voice discussing intellectual topics quite restful, as if I’d been transported to a calm, softly lit lecture hall at Stanford, and continued to listen more and more and more of what Mr. Thiel had to say.

At the outset, what struck me the most about Mr. Thiel was his stance on death. He was self-identifying as a Christian in public, unusual for a man of his class, but he also seemed to be terribly too interested in immortality and seemed to view death as a categorically bad thing to be avoided. I had the opposite position; after reading The Martyrdom of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas for a freshman humanities seminar, I set out to write a first-person short story just so that I could better relive every imagined gruesome, ecstatic moment of St. Felicity’s death by wild animals and inhabit her mindset of gloriously dying to give birth to a better world (Sounds like communism to me, Kristin!, you might say). I very much came to Mr. Thiel with the firmly held belief that Christians should be very eager for death and the afterlife. As I began my foray into his thought, I kept asking myself the question, “How can Peter Thiel both be a Christian and be so anti-death?” It wormed its way into my brain like a burr in my shoe and bothered me. I couldn’t get it out. His position seemed so obviously self-contradictory, and yet he was so intelligent I was almost horrified and embarrassed for him that he didn’t seem to see it himself. I felt sure that Mr. Thiel’s anti-death sentiment was due to some spiritual immaturity, but I was familiar enough with him to know that he might possibly have an intellectual argument to bridge this gap, even though I was absolutely clueless as to what it might be, so I set out to find it, if it existed.

Hundreds of hours of research, listening, reading, and thinking later, I formulated a robust, relatively coherent theory of the universe of Mr. Thiel’s thought and I answered my question. But not only that: my deep-dive into the “Thielverse” changed me. I came to believe that Christianity was not a nice, inoffensive religion to practice, but rather the very alchemy by which the utopian future and the God-given destiny of humanity could be conceived, which would include the greatest miracle of all: deathlessness.

*All transcripts cited below have been lightly edited for clarity.

Erst: Er Ist Ein Deutscher1

“He’s against freedom of the press.” “He doesn’t want women to have the right to vote.” “He’s a Nazi.” “He’s a fascist.” “He’s a sociopath.” “He’s a vampire.” “He’s a nihilist.”

One of the reasons I believe that Mr. Thiel gets dragged more often than he should is because American culture very strongly orients itself toward a very particular mode of self-expression in personal mannerisms and interpersonal interactions and is often very exclusive toward other modes to the point of deep suspicion. Mr. Thiel, in his public appearances, doesn’t smile much or speak very effusively. He is somewhat guarded, reserved, flattened in affect, and impersonal. Many Americans seem to take this as some sort of sign of misanthropic psychopathy or desperate, calculating hunger for power, and this resulting unease about him then becomes supporting evidence for whichever of the arguments listed above are favored, but I suggest the obvious: he is just German.

The German people are, by and large, in possession of personality traits that make them skilled engineers (take a drive through the Alps in a BMW that handles like buttah and you’ll forget all about your homeland) and highly meticulous, organized, and conscientious, but no one has ever accused them of being ebullient except when excessively inebriated while clad in Tracht at Oktoberfest.

I found this dichotomy between American and German expression most starkly expressed in an interview Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times had Mr. Thiel and venture capitalist Chris Sacca. Mr. Thiel sports a modern European look, as if he had just stepped off a train into the Berlin Hauptbahnhof for a meeting, wanting only for a Freitag bag slung over his shoulder, while Mr. Sacca wears a very flamboyant and eye-catching Western shirt, complete with cowboy boots that have never seen a ranch. Mr. Sacca smiles frequently, makes jokes, and shares personal stories of Uber (Über, umlaut bitte, argh) founder Travis Kalanick hanging out in his hot tub at Tahoe and beating Mr. Sacca’s father at Wii Tennis. The most notable comments are at the end, when an expectant father in the audience asks Messrs. Thiel and Sacca if he will be able to afford college for his child in 18 years’ time:

MR. SACCA: Well, he [Mr. Thiel] doesn’t have any thoughts on college —

MR. THIEL: Well, [the cost of college] will keep going up until someone does something to change it. You know, the future doesn't exist in this — look, I want to key off what Chris said about entrepreneurs: you can say something definite about the future when you create it. You can't say something definite about about it in terms of just something that exists out there. So the cost of college, you know, will keep going up at a faster-than-inflation rate, ‘til people develop alternatives that work, educationally and from a signaling perspective, and socially, in all the different ways college works. Until it happens, it'll keep going up at a rate faster than inflation.

MR. SACCA: I mean, I deeply believe in the value of college, particularly a liberal arts education. I'm a little bit of an outlier in that I think college is an opportunity to learn with a capital “L”; later, you can train. What I worry about is how uni-dimensional a lot of computer science students have become as a result of the rigor of the curriculum. They don't get to study abroad anymore, they don't have summer jobs, they've never waited in any tables, and so what you get is a 23-year-old engineer at Google yelling at the chef because they've run out of pheasant that day, and they don't understand how people get by in the developing world, they've never met anyone who's struggling to pay back loans or payday financing a check, and so I really worry about how homogenous our culture is getting, or within Silicon Valley, because of the lack of opportunities. So I deeply believe that college isn't necessarily the requisite vocational training at all, but I certainly look around and I see that some of the most interesting people I know like Stewart Butterfield, who runs Slack. He's successful because he's fascinating, interesting, has had this wealth of experiences in his life, and so I hope that it's at least affordable enough to get your girl to college.

Mr. Thiel’s answer to the expectant father categorizes the problems with college and notes how there is a definite vision needed in order to change the cultural morass around college and college education. Moreover, Mr. Thiel has constantly beat the drum about college, referring to it time and again as “an insurance policy against falling into the very large cracks in our society” and as a cumbersome multi-dimensional product that is some hybrid of status signaling and mating opportunities for further entrée into the upper echelons of class and power, a four-year party, an insurance product, and a lack of any other ideas on how to spend the ages 18 to 22 without dooming oneself to a lifetime of asking “Do you want whipped cream on that?” ten hours a day six days a week until death is seen a mercy. Additionally, Mr. Thiel funds the Thiel Fellowship, which allows students with promising (definite) ideas to take a leave of absence from university in order to realize their ideas.

Mr. Sacca’s response, by contrast, is ultimately incoherent, because he talks about the importance of a liberal arts education and then goes onto discuss a host of life experiences that have nothing to do with college, like living in another country (entirely doable without the university) and waiting tables (again, doable without the university). He briefly comments about how college “isn’t necessarily the requisite vocational training” then goes on to remark about a CEO friend of his who is very fascinating, which has made him successful. He concludes his comment with an empathic nod to the questioner, complete with slightly downturned eyes to demonstrate his sadness, as if he hopes the poor father manages to sell enough plasma in the next two decades to fund his daughter’s college education so that she too can become fascinating and run a workplace messaging app.

But many Americans would find themselves much more openly receiving Mr. Sacca’s response, because he says it in such an American fashion. His argument isn’t entirely clear, but he says it warmly enough and he pays several nods to the lower-classes with his comment about the chef at Google and the need to empathize with those who pay payday loans and struggle to make ends meet. Americans want to see not necessarily real solutions to their problems (as Mr. Thiel offers) but proper signaling from the wealthy that they empathize and care about the lower classes. This is not to say that there is no value in the wealthy empathizing with the downtrodden of the Earth, even on the face of it, but many Germans would not overly and expressively empathize in person with people they do not know or give an answer that might feel “fake”, even if they intellectually recognize problems with economic disparities and do actually personally empathize. This cultural discrepancy between American signaling of social connectedness versus German expression of actual social reality is a reason why Wal-Mart failed in Deutschland:

“For some reason, a few American businesses have this false belief that every western country has the same culture as theirs — but it’s simply not true. […]

In America, it’s not uncommon for retail assistants to get all chatty and friendly with the customers. Walmart decided to train its German employees to do the same. The cashiers were told to smile at customers during checkout. Oh boy, did that backfire…

Smiling at random strangers and acting like you know them isn’t really German. I mean, it might happen every once in a while, but it’s certainly not an integral part of the German culture.

Hans-Martin Poschmann, a renowned union secretary, said: ‘People found these things strange; Germans just don’t behave that way.’”

Those who find Mr. Thiel’s Germanness off-putting to his message should instead imagine his talks as being run through an AI script called “Americanize” that adds frequent pitch changes, emphatic words, laughs, toothy smiles, excessive eye contact, touch, and broad hand gestures, and that perspective may help dampen the sour reaction fueled by the predominance of German expression in Mr. Thiel’s personal manner and properly orient the American toward what he actually has to say.

The Modern-Day Princes of the Holy-Roman-American Empire

I never lead with describing Mr. Thiel, or anyone else of that strata of net worth, as a billionaire, because it’s such a novel concept to us socially as humans that we have no idea what it means. What do billionaires do, besides go about professionally having lots of money?

So how can we understand people like Mr. Thiel and his ilk, the “billionaires”? I take my cue from a book for which Mr. Thiel wrote the preface in a reissued 2020 print and which certainly influenced him: The Sovereign Individual. Even though I could not roll my eyes hard enough at the authors’ anti-Catholic, hyper-individualistic proto-tech-bro-pseudo-intellectualist-modernist maligning of the medieval Roman Catholic Church, the book does provide a constructive lens by which we can understand the political sphere of medieval to early modern Europe and this lens can be fairly extrapolated to our own time more than we might think.

I suggest instead — though people of this class would certainly on the whole dislike this formation, I press on, because it is more accurate — that we understand the very high net worth individuals as princes nestled within the modern day Holy Roman Empire that is America. The Holy Roman Empire coexisted with its own prince-electors, who had enormous degrees of personal power and authority as well. When we come to understand the high net worth individuals as princes, with sizable financial resources, political relationships, and networks of allies and companies that produce important and oftentimes critical products and services, our understanding becomes much more concrete and less abstract than apprehending them as “billionaires”. This is why people like Elon Musk don’t fit into our society and our government the same way a middle-class John Doe might. To reach back to our Holy Roman Empire frame, John Doe might be the modern version of a shopkeeper in Stuttgart, but Mr. Musk is functionally Prince Elon of the Haus-von-Tesla-Twitter-und-SpaceX. He is a juggernaut unto himself, and while the Holy Roman-American-Empire will be largely free to do with Mr. Doe as it pleases, provided it does not openly violate any social contracts that would spark a mass rebellion among the people (and, to be fair, the social contracts between the Holy-Roman-American-Empire and the Does who inhabit her are relatively equitable to the Does compared to historical and even other contemporary relationships between governments and the Does), approaching Prince Elon is a different matter altogether, somewhat akin to negotiating with a foreign government.

This dynamic explains why the princes give political donations. Political donations are good sense when you’re of high net worth and linked in with a veritable fiefdom. It’s maybe up there even above “brushing your teeth” in the personal care checklist once you reach a certain strata of wealth, especially if you live in a stagnant or declining economy. For the princes, political donations can be seen as a form of taxation: a means by which they compensate the Holy-Roman-American Empire for the inconvenience that they cause by their unwieldly existence and give themselves some degree of protection. After all, it’s Mark Zuckerberg, not your crazy aunt Karen, who gets pulled by the scruff of his neck like a wayward cub in front of a congressional committee to testify under oath about disinformation on Facebook. If you had that kind of political exposure, you’d shell over your hard-earned dollars and host extravagant fundraising dinners at your Mediterranean villa in Napa too. One might argue that the political-donations-as-taxes are not going toward helping people who need it the most, but the reality is that a majority of federal income taxes go to support many unpleasant causes, so funding Senator Gracchus’ reelection campaign so that he can buy pizza for his staffers and TV ads to run during “Wheel of Fortune”, both of which ultimately support employees at Domino’s and professional cameramen, may be a relatively less morally harmful use of money. We’re free to dislike these arrangements, but they continually constitute themselves in human political organizations, and violent revolution after violent revolution only becomes a game of musical chairs to reset those in power, but somehow never manages to eradicate these structures altogether. There are two options to changing this dynamic: one is to reduce or eliminate political donations altogether, which would make the political world more insular and more strongly oriented toward pre-existing relationships and obscured exchanges of favors, an invitation-only country club where everyone already knows each other and new entrants are not able to buy their way in to a seat at the table, and the other is to reduce the amount of political influence in everyday life altogether.2 As long as every dollar invested in politics returns an amount higher than the market, there will be strong incentives by those who have money and skin in the game to lose— the princes — to over-invest in politics relative to investing in our economy.

(Lest the dynamic of the princes upset any, remember the universities. The universities are essentially quasi-private cities with non-taxable wealth, their own private police forces who can expel persons from their perimeter ala the Medici, and their denizens enjoy a quality of life unparalleled in America, with astonishingly low rates of crime, educational and life enrichment activities, a close-knit community feel, density, cleanliness, walkability, and the universities have even had the power to adjudicate some legal claims. Imagine if Uber was able to adjudicate assault claims between employees! We’d find that very strange.)3

So, because so many princes engage in political donations, Mr. Thiel, also a prince, is occasionally accused of “buying Senate seats,” but here too he is differentiated from his fellows. If he wanted to buy a Senate seat — paying the powers as a form of personal insurance, basically a job USAA could do if our culture permitted us to have this conversation more openly — he could do so very easily, with much less blowback and almost no fanfare. You’d never read about it, just like you never read about all the other princes and fiefdoms who participate very much in our political system, too. This is a relatively simple process well within his intellectual capacity to grasp. He’d simply choose safe, boring candidates who polled well, didn’t have too much baggage, smiled nicely for the cameras, had a high likelihood of winning, scatter a bunch of money across a variety of all those candidates and their PACs, head out to dinner and drinks, and call it an election cycle. He doesn’t seem to organize his political life that way, though. Instead, he seems to have a different, more far-reaching goal in mind beyond personal gain, one that arguably has cost him more personally than any dollar he has ever donated.

A Middle Class Man

But despite his status as a prince, Mr. Thiel won’t let us categorize and dismiss him so easily. Entrepreneur Noah Kagan commented of meeting Mr. Thiel, “There’s a lot of interesting things about him. One that I tweeted about […] He just uses like, an iPhone 7. […] He had, like, crappy-[a**] New Balances; he looks like he was wearing Mervyn socks and Wrangler jeans.”

It is intriguing that Mr. Kagan was so struck with Mr. Thiel’s monastic choice in iPhones. First, it seems plausible that Mr. Thiel has chosen to have iPhones several generations back from $Latest$Model is because it is probably altogether too depressing for the futurist Mr. Thiel to remember multiple times a day as he uses his phone that $Latest$Model is the best that Apple has to offer in phones, and that he is not using something far zippier and more futuristic. Mr. Thiel’s book title, Zero to One, seems a repudiation of the faux-progress promulgated by the constant iterations on the Apple iPhone, which is to go from iPhone 1 to n rather than make something new altogether.

Second, Mr. Thiel came out of the middle class himself and, in spite of his wealth, is ultimately a very middle class man, as Mr. Kagan’s other comments note. In “The Tech Curse” at the National Conservative Conference earlier this year in Miami, a speech in which he discussed California and touched on Florida, Mr. Thiel again turned to the issues of the middle class:

“The cautionary note in my judgment would be, if we are going to have a high growth alternative, the real estate version of the test is, do the real estate prices come down? Do they stay cheap? And, fact that real estate in Florida or Texas has melted up over the last two three years is not evidence that you're succeeding in building a better model than California. I worry that that's evidence that you're you're becoming like California. I bought a place here in Miami in September 2020, $18 million, whatever, it's now, you know, $35 million. It's great as as an investment, but it would be so much healthier if this was just a bubble and the prices would collapse and it would all go down 50% again. Because, unlike California, you could build a lot of things. It might take a few years, but that's sort of the open question I would say about Texas and and Florida — are they still places where you can genuinely have affordable housing? I always think the thing that's very confusing about housing is it's both a real asset and a virtual asset. So, you think of a house as a nest, as a place to live, in which case you want a big house that's affordable, not too expensive. And then you can think of a house as a nest egg, as a number on an Excel spreadsheet, where as long as the number goes up, you don't care whether it's a rat-infested apartment in Manhattan or anything like that. Surely, the much healthier alternative to California has to be one where it's it's cheap. It never overshoots. This is not how you're gonna make money, by housing. It’s really just a place for middle class people to live. In general, this is sort of a challenge I would pose to all of you is: how do we do better than California? We can go with a nihilistic negation, we can we can denounce it in all these ways, but the question is always, ‘how can we do better?’ How can we concretely offer a vision for the 21st century that's better than the California alternative?”

He nonchalantly slips it in there, but Mr. Thiel just offhandedly makes a comment that he wishes his multi-million dollar house in Florida had declined in value so it would be a sign that middle class people could more easily access housing. He seems very invested in the ability of the middle class to access upward mobility. He speaks as if he cares about his roots, which are certainly middle class. Mr. Thiel wasn’t born into the upper crust of society, with a silver spoon in his mouth on the East Coast, going up through Exeter and into Harvard, into a life already full of social and political connections and summers in Montauk. He went to public high school in California and earned his way as an immigrant son into Stanford. He may be a veritable prince, but his care seems to be for the middle class through and through, for those Americans so much like the people who must have surrounded him in his own upbringing.

An Anti-Nihilist in Plain Sight

The first I heard Mr. Thiel accused of being a nihilist was in Max Chafkin’s 2021 biography of him, The Contrarian. I’ve heard many disparaging remarks against Mr. Thiel, but this one absolutely drove me up the wall, as I discussed in my review of the book. Even though I strongly feel that the other remarks are ultimately baseless, one can at least squint and see their origins, but to accuse Mr. Thiel of being a nihilist is just beyond, and it pained me to see the biographer do himself such a great disservice. The accusation only appeared twice in The Contrarian, first in a story surrounding a dispute between Curtis Yarvin and Thiel fellow John Burnham. The way Mr. Chafkin told it, he questioned whether Mr. Thiel “really believed in anything” because Mr. Thiel (per Mr. Chafkin) sided with Mr. Yarvin over his Thiel fellow in a legal dispute over the company Tlon/Urbit. The story seems so drama-laden and fact-specific that it’s extremely difficult to pass any judgment as a bystander-reader beyond wishing well to all involved and having another sip of wine, but the last place I’d reach is suggesting that he’s a nihilist for whatever role he had in this bizarre, niche story. The second comment was Mr. Chafkin quoting some person who said that Mr. Thiel is a nihilist, with no further explanation to support it.

Author Luke Burgis also picked up the absurdity of this comment, calling the accusation that Mr. Thiel is a nihilist “an outrageous claim”. He also asked Mr. Thiel about Mr. Chafkin’s remarks:

“‘Man, I feel I am an extreme opposite of a nihilist,’” Thiel tells me.

‘I believe in ideas. Maybe I believe in ideas too much. I think back to some ideological debates, like the ones on campus at Stanford, and I actually believed there were people on the other side of these debates — I thought we were actually talking about ideas. But now I have a much more mimetic read on it. I think the people who are ideological are in the minority.’”

Mr. Thiel must congratulate himself, however; he must have been doing such a successful job at hiding in plain sight, because I agree with his self-assessment that he is actually extremely anti-nihilist and pretty much every word that comes out of his mouth in public is dripping with anti-nihilism and is an all-but-naked (albeit Germanic) plea for people to come to their senses, shake out of the ethereal world of the mind, and engage in the real world and with real problems again. He is hardly running around blasting Rammstein — “weiter, weiter, ins Verderben, wir müssen leben bis wir sterben” — and suggesting we all put paper bags over our heads and wait for the Giant Meteor ‘16 to hit us.

Mr. Thiel seems to want people to discover who they are for themselves rather than in all these mimetic games we constantly play. The more we engage in these fake mimetic games that are all in our head (although the consequences are all too real) the more we allow the very material and very real world in which our bodies reside to fall to pieces all around us. We are our own Neros now, dancing to the music of our fiddles as our empires burn, but Mr. Thiel will never give up calling this out.

The Future Exists, and We Should All Want to Live There

Undoubtedly, what first caught my attention about Mr. Thiel was that he talked about the future. He didn’t just speak of dull revenue projections plotted over a graph like an ordinary businessman who would be lauded across the Journal. Instead, he spoke of the future vividly, as if it was something that should look different and feel exciting, and he seemed to be the only prominent person in the world who was calling attention to the fact that we hadn’t had the future that we were promised to date from the 1960s on, and that this was a very disconcerting trend for what the future was looking like from this point forward:

“New technology has never been an automatic feature of history. Our ancestors lived in static, zero-sum societies where success meant seizing things from others. They created new sources of wealth only rarely, and in the long run they could n ever create enough to save the average person from an extremely hard life. Then, after 10,000 years of fitful advance from primitive agriculture to medieval windmills and 16th-century astrolabes, the modern world suddenly experienced relentless technological progress from the advent of the steam engine in the 1760s all the way up to about 1970. As a result, we have inherited a richer society than any previous generation would have been able to imagine. Any generation excepting our parents’ and grandparents’, that is: in the late 1960s, they expected this progress to continue. They looked forward to a four-day workweek, energy too cheap to meter, and vacations on the moon. But it didn’t happen. The smartphones that distract us from our surroundings also distract us from the fact that our surroundings are strangely old: only computers and communications have improved dramatically since midcentury. That doesn’t mean our parents were wrong to imagine a better future— they were only wrong to expect it as something automatic. Today our challenge is to both imagine and create the new technologies that can make the 21st century more peaceful and prosperous than the 20th.”

— Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future by Peter Thiel and Blake Masters

Mr. Thiel notes that we simply can’t take the future for granted. He argues in Zero to One for “definite optimism” in which we can be optimistic about the future because we have a definite plan for what it will look like and how we will get there. The future is real — it will happen — and we should very much hope that is a future that we want to live in.

This surely resonated with me because, from a young age, it was always the 1989 cult-classic film Back to the Future: Part II that I would demand to watch again and again in between doodling flux capacitators and explaining to adults inquisitive about my artwork that “this is what makes time travel possible”. Like a tiny mental patient, I had a ritual at each viewing in which I would drag my wooden rocking horse across the living room, plop myself on it inches from the T.V., and rock the horse faster and faster and faster as the DeLorean worked up to 88 miles per hour, at which point I would finally stop forcing the horse and ride out the energy, and watch as Doc, Marty, and Jennifer arrived via flying DeLorean to the futuristic world of 2015. I was enthralled. There were doors that opened with just a touch of a thumb. Clothes were self-drying, the benefits of which were obvious to me even at four before I started my life with laundry; shoes, for someone who was still struggling with laces, miraculously fastened themselves. A giant pizza (my favorite food) could be made instantly with a press of a button from a packet the size of a credit card. Cars flew, and, most importantly for a four-year-old girl: there were pink hoverboards. All these little small but highly visual scenes very much impressed themselves on me as vignettes of hope in what the future could look like and how magical it might be.

Therefore, it took little for me to be sympathetic to the Founders Fund manifesto when I read it in my old age: “We wanted flying cars and instead we got 140 characters.” Silently striking “flying cars” for “pink hoverboards,” I could feel my inner four-year-old’s disappointment at how 2015 turned out relative to the cultural dreams that we had dreamed at the end of the nineteen-eighties.

The Trump Problem

Much concern around Mr. Thiel centers on his 2016 support for and endorsement of Donald J. Trump to the American presidency. But first, we must frame the reality of Pres. Trump’s legacy in the full context.

Pres. Trump brings up many emotions, to say the least. However, it is also important to remember our own predilections to rewrite history and mythologize the past. The chances of Pres. Trump being widely remembered in 50 years’ time as a “nice, moderate Republican” with feelings of amusement, nostalgia, and affection, are much higher than those of his being remembered as an untouchable, terrible Adolf Hitler sentenced to an eternity of damnatio memoriae. One is free to disagree and insist on the similarities between Pres. Trump and the NS-Staat Führer, but there is a crucial difference: the Americans were in charge of the narrative about the NS-Staat, and, barring any future colonization or occupation by a foreign power, the Americans will be in charge of the narrative about Pres. Trump, too.

Contemporary Americans never discuss the Entnazifizierung or JCS 1067; it’s a subject seldom taught to American schoolchildren. One perspective of the Entnazifizierung is that the American government and the Allied powers were genuinely horrified by the objectively egregious human suffering perpetrated by the NS-Staat, and felt it incumbent upon them to shame the German populace to the error of their ways lest another such grievous moral sin be committed by them. Another perspective is that the Entnazifizierung was a key piece in a constructive rationalist approach to fully demilitarizing the German people. With the Entnazifizierung, the Americans reshaped a narrative in almost real-time, retelling the story of the NS-Staat to the Germans who had just lived through it, who had all very recently understood the enterprise of the NS-Staat as the planet’s most noble project of creating a Thousand Year Reich and freeing the Germans from enemies within and without to reach new heights of man, to a different story: the German people themselves were the most revolting, worst of all villains, responsible for heinous moral crimes at which every nation in the world recoiled in horror and disgust. So, narratives can change, be reshaped, often much more on a dime than we might like to think.

But Pres. Trump is an American, and an American president to boot, so he will not likely receive the same treatment as the foreign NS-Staat. Taking our uncomfortable, strife-riven present and mythologizing it in the future into a glorious, even if tainted, past, is important, and almost all we ever do. We must, to some degree, if we wish to continue on as a nation-state, because it’s very dangerous to question the past once it’s sufficiently past. Note how we don’t argue anymore about the validity of the 2000 Florida vote count and its subsequent impact on the presidential election. Nation-states are built on myths; these myths always support the construction of a society within the nation-state. Our society is how we transact, have friends, make families, order Christmas presents, do woodworking, hold jobs, grow careers, save money, entertain ourselves, and worship. Our society is the air we breathe and the water in which we swim. Therefore, these myths, our own history, become in time the ground of our present, of our priceless social fabric, all these many thousands of spoken and unspoken negotiations and agreements, and if we begin to question the past, we risk pulling the thread that ties together the tapestry. This is why the 1619 Project is so controversial, not because anyone sane really denies the role that the brutal slavery of Africans played in producing economic surplus in America, but because it calls into question the mythology of the American founding. Similarly, the French Republic manages to function relatively well as a nation-state today in part because it never questions the thousands of bloody, terrible murders that birthed it.

There is an easy and well-trod path forward for Pres. Trump to be codified positively into history, no matter what we think about him today: Abraham Lincoln admirably freed slaves (albeit for political and not moral reasons), but was arguably antagonistic to a host of civil rights and was certainly hardly a liberal abolitionist of his day, having represented a slaveowner to have an escaped slave family returned to him — so the mother, Jane Bryant, and her children would be sold off and possibly even separated from each other after Ms. Bryant, a lifelong slave to the Matson family and very likely occasional paramour to the head of the household, had gotten into a dispute with the white housekeeper Mary Corbin, the future Mrs. Matson — but Pres. Lincoln, despite his practice of what one paper called “an adherence to moral neutrality”, still has a towering monument in the nation’s capital before which the most gifted orators like Pres. Barack Obama have given lovely speeches honoring his memory. Even in more recent times, Pres. George W. Bush has seen a remarkable transformation from being burned in effigy many times the world over, and almost universally loathed by the entire American left as a warmonger and election-stealer, to sharing candy with First Lady Michelle Obama, a gesture which earned him the most flattering of praise and coverage across the whole of media, while all the many life-altering decisions he made while in office remain yet to be fully examined. The Iraq Invasion — shock and awe which set off a new wave of horror and repulsion at the then-President — was just almost 20 years ago, well within the living memory of millions of American voters. Yet, time heals all wounds, bringing in her hands a MasterClass on leadership too.

All that to say, as impassioned as one might feel in the moment about Pres. Trump and his threats to democracy and the United States, one must always recall the inevitable perspective of history. Is how we read today’s events as important as how we will read them 50 years from now? I would argue no. The tides of time will wash over even all the intricate sandcastles that we childishly thought would stand forever.

That Essay

Before he came to infamy as a Trump supporter, Mr. Thiel came under one of his most prominent post-PayPal firestorms when he made a statement about women’s suffrage — a comment half-made offhand between Emily Dickinson-esque dashes — in a 2009 Cato Unbound essay, “The Education of a Libertarian” (and in a really amusing way, the backlash against his comment must have surely turned out to be a fulfilment of the title for Mr. Thiel):

“For those of us who are libertarian in 2009, our education culminates with the knowledge that the broader education of the body politic has become a fool’s errand.

Indeed, even more pessimistically, the trend has been going the wrong way for a long time. To return to finance, the last economic depression in the United States that did not result in massive government intervention was the collapse of 1920–21. It was sharp but short, and entailed the sort of Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’ that could lead to a real boom. The decade that followed — the roaring 1920s — was so strong that historians have forgotten the depression that started it. The 1920s were the last decade in American history during which one could be genuinely optimistic about politics. Since 1920, the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women — two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians — have rendered the notion of ‘capitalist democracy’ into an oxymoron.

In the face of these realities, one would despair if one limited one’s horizon to the world of politics. I do not despair because I no longer believe that politics encompasses all possible futures of our world. In our time, the great task for libertarians is to find an escape from politics in all its forms — from the totalitarian and fundamentalist catastrophes to the unthinking demos that guides so-called ‘social democracy.’”

Mr. Thiel notes the same exact same issue that many libertarian women have noted (see Pamela J. Hobart’s “Why Aren’t More Women Libertarians?” and Sharon Presley’s “Why Are There So Few Women Libertarians (Redux)”). In the spirit of representation, there are many female libertarians who understand that there is less libertarianism in their society than they personally would prefer because female voters, on aggregate, align themselves much less with the Libertarian Party or even libertarian policies; this is clear in polling data and in election results.

As Mrs. Hobart later commented, the reason that women may not be libertarians may be because…. women simply aren’t libertarians; i.e., their political preferences do not align with libertarianism. It seems entirely possible Mr. Thiel broadly agrees: he is not taking to the pages of Cato to chide its readers for failing to help women find the secret and yet heretofore undiscovered fount of libertarianism that had always awaited deep within the feminine psyche.

But nowhere does Mr. Thiel say women should not have the right to vote and any argument to the contrary misses the entire point of his essay. “The Education of a Libertarian” is a cri de coeur of a man calling for a new movement of Libertarians Going Their Own Way (LGTOW), which is exactly what he goes on to write about. The remainder of the essay explores ways in which libertarians can leave politics behind, not engage in it further by embarking on wholesale structural changes to the political system that would be surely destined to fail from the start.

Certainly, the reason Mr. Thiel’s comment seems to touch so many nerves is that there have been injustices perpetrated against women all the world over throughout all history, and there is a strong cultural belief in the West that enfranchisement helps reduce these injustices by giving women (and other marginalized persons) a voice to participate in governance through their vote. Mr. Thiel’s mistake here was not an inadvertent suggestion that women should be disenfranchised (because he never said that), but rather that he engaged in a pattern of behavior very typical for him without fully considering the ramifications on such a touchy issue — and who knows, perhaps he’d thrown back one too many cans of Red Bull before he sat down to type (it gives you wings, but maybe only to fly too close to the sun). Anyone who has ever spent time listening to Mr. Thiel knows that his first instinct is to always categorize when faced with a question of “Why does X outcome occur?” It’s easy to see the way he does this in the above quote about college. His natural, default wiring seems to be to either reframe the question if he believes it’s not framed correctly or backtrack to find the exact point at which X outcome began to occur and identify the reasons that caused X outcome. It’s simply how he works with concepts. He was attempting to explain an answer to the question of “Why was the U.S. on a path to a capitalistic, libertarian, growth-oriented society, when did that change, and why?”

Get to Growth

Returning to Mr. Thiel’s support of Pres. Trump, as well as his clear preference for libertarian political outcomes, I offer only this defense, but I remain quite sure about it: Mr. Thiel cares much less about Pres. Trump, women’s suffrage, fascism, authoritarianism, libertarianism, Burning-Man-at-Sea, money, power, Bay Area rationalists, blood transfusions, the singularity, selling books, or fame than he does about real, meaningful, productive, and healthy economic growth. It’s my belief that economic growth is the single most important frame through which he sees all of politics and policy, perhaps second only to mimetic theory. To my mind, anyone seeking to argue against his political positions must first either assert that economic growth is not the leading cause of health, wealth, and well-being in a society, or must successfully assert that their positions better advance economic growth.

Economist Tyler Cowen covers this in The Great Stagnation (which is dedicated to Mr. Thiel):

“We still have electricity and indoor plumbing, but most people already use them and we take their advantages, economic and otherwise, for granted. The problem is not that we are likely to regress, but rather where the future growth in living standards will come from. It’s harder to bring additional gains than it used to be.”

It’s a defensible argument that economic growth, particularly at a certain level, is extremely crucial for the continued well-being of a society. This is not a “Save the Billionaires” post, but even if we want to tax the billionaires (and multi-millionaires, and the upper and middle echelons of the middle class) in order to promote wealth re-distribution rather than organically growing wealth in the lower classes, at some point, if we are not very careful in continuing to focus on a healthy clip of economic growth, we can absolutely run out of billionaires and everyone else to tax. It would be a fatal mistake to assume that wealthy people and their wealth will be with us indefinitely and that we can always tap forever from this well.4

Societies that fail to grow have three options before them: collapse (in which quality of life grows steadily worse, civil war breaks out, and the landscape looks something like the Walking Dead, with every six-year-old being armed with an AR-15 as they traipse off to look for half-empty soup cans in landfills), reform (which can be positive or negative, such as the hyperinflation and economic ruin that resulted in the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the terroristic NS-Staat), or expansion (war and encroachment on other territories for resources, which often causes great human suffering and senselessly ends the lives of many innocents). We can avoid all of those (only one of which, positive reform, is morally good, but it is also the least likely outcome since it requires the most conscious effort) by simply making sure our economy is growing at a sufficient pace. Growing our economy helps ensure mobility of the lower classes into the upper classes, provides opportunities for people to engage in meaningful work, gives people financial freedom to have an array of choices in their lives, and allows for much improved opportunities all across the board, solving a host of other social problems with it. Is it a cure-all? Certainly not. But it helps, a lot, and we must have it if we wish to carry on as a society.

His speech at the 2016 Republican National Convention tells us his focus in endorsing Donald Trump for the nomination and presidency:

“I'm not a politician, but neither is Donald Trump. He is a builder and it's time to rebuild America. Where I work in Silicon Valley, it's hard to see where America has gone wrong. My industry has made a lot of progress in computers and in software, and of course it's made a lot of money, but Silicon Valley is a small place. Drive out to Sacramento, or even across the bridge to Oakland, and you won't see the same prosperity. That's just how small it is. Across the country, wages are flat. Americans get paid less today than 10 years ago, but health care and college tuition cost more every year. Meanwhile, Wall Street bankers inflate bubbles, in everything from government bonds to Hillary Clinton’s speaking fees. Our economy is broken. […] This isn't the dream we looked forward to back when my parents came to America looking for that dream. They found it right here in Cleveland. They brought me here as a one-year-old, and this is where I became an American opportunity was everywhere. […] When I moved to Cleveland, defense research was laying the foundations for the Internet, the Apollo program was just about to put a man on the moon, and it was Neil Armstrong from right here in Ohio. The future felt limitless, but today our government is broken. Our nuclear bases still use floppy disks. Our newest fighter jets can't even fly in the rain, and it would be kind to say the government software works poorly, because much of the time it doesn't even work at all. That is a staggering decline for the country that completed the Manhattan Project. […] Instead of going to Mars, we have invaded the Middle East. We don't need to see Hillary Clinton's deleted emails, her incompetence is in plain sight. She pushed for a war in Libya and today, it's a training ground for ISIS. On this most important issue, Donald Trump is right. It’s time to end the era of stupid wars and rebuild our country.

When I was a kid, the great debate was about how to defeat the Soviet Union, and we won. Now, we are told that the great debate is about who gets to use which bathroom. This is a distraction from our real problems. Who cares? Of course, every American has a unique identity. I am proud to be gay, I am proud to be a Republican, but most of all I am proud to be an American. I don't pretend to agree with every plank in our party's platform, but fake culture wars only distract us from our economic decline, and nobody in this race is being honest about it except Donald Trump. […] When Donald Trump asked us to make America great again, he's not suggesting a return to the past, he's running to lead us back to that bright future.”

The speech shows that Mr. Thiel’s interest in Donald Trump (at least in 2016) is due to his belief that Pres. Trump was the candidate who was most invested in improving the issue that Mr. Thiel seems to care about the most: economic growth. One can argue against his support for Pres. Trump, but it’s important to understand the nuances of his stated reasoning first. Apart from a Libertarian Party candidate (whose chances of winning are, as discussed earlier, slim), it would be difficult to imagine other candidates in both the primary races and the general who were as openly vocal about correcting economic decline as Pres. Trump. Whether Pres. Trump was the right person to do that, is a separate question, but it should not at all seem surprising that Mr. Thiel would have supported him on the basis of hoping to find a path forward to increase economic growth in America.

In a recent interview with Peter Robinson, Mr. Thiel emphasized this again: “I would like to get back to growth. I would like to get back to growth that is not inflationary, not cancerous, and not apocalyptic. We should figure out how to do this in a detailed way; there probably are some tax cuts that are part of it, there's a lot of deregulation that's part of it. It’s a fairly hard thing to do.”

“X Saves the World”

On that note, Mr. Thiel, with a 1967 birthyear, is far more formed by his membership in the sandwiched and oft-forgotten Generation X than is ever really noted. It makes him a well-positioned critic of the Baby Boomers, because the Baby Boomers are quite starry-eyed, manic-pixie-dream-children of summer, characteristics which made them pioneers in music and art, but they are really unaware of their own ignorance, instead thinking of it as unparalleled genius that desperately needs sharing throughout the social fabric, and so it is with a relentless drumbeat that they have shouted their ignorance-disguised-as-wisdom on matters economic, political, and social through every American institution that we have, fundamentally setting America back at least half a century. We don’t appreciate this enough.5

To Mr. Thiel’s mind, the Boomers are “indefinite optimists”, which he defines in Zero to One as someone who believes that “the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans.” He goes onto describe the Baby Boom:

“The strange history of the Baby Boom produced a generation of indefinite optimists so used to effortless progress that they feel entitled to it. Whether you were born in 1945 or 1950 or 1955, things got better every year for the first 18 years of your life, and it had nothing to do with you. Technological advance seemed to accelerate automatically, so the Boomers grew up with great expectations but few specific plans for how to fulfill them. Then, when technological progress stalled in the 1970s, increasing income inequality came to the rescue of most elite Boomers. Every year of adulthood continued to get automatically better and better for the rich and successful. The rest of their generation was left behind, but the wealthy Boomers who shape public opinion today see little reason to question their naïve optimism.

Malcolm Gladwell says you can’t understand Bill Gates’s success without understanding his fortunate personal context: he grew up in a good family, went to a private school equipped with a computer lab, and counted Paul Allen as a childhood friend. But perhaps you can’t understand Malcolm Gladwell without understanding his historical context as a Boomer (born in 1963). When Baby Boomers grow up and write books to explain why one or another individual is successful, they point to the power of a particular individual’s context as determined by chance. But they miss the even bigger social context for their own preferred explanations: a whole generation learned from childhood to overrate the power of chance and underrate the importance of planning. Gladwell at first appears to be making a contrarian critique of the myth of the self-made businessman, but actually his own account encapsulates the conventional view of a generation.”

Per Mr. Thiel, the Baby Boomers have failed to properly plan for the future (in a definite way) because they were enculturated into an indefinite optimism where it wasn’t at all clear to them that there was a relationship between their choices and policies and resulting effects on the world in which they live. This makes economic growth challenging to assume.

No one captures the spirit of the manic-pixie-dream-children that are the Boomers quite like Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which I quote at length because it is so descriptive:

“The guy brings charges against Kesey for ruining his engine and Kesey ends up in juvenile court before a judge and tries to tell him how it is at Gregg's Drive-In on a Saturday night: The Life—that feeling—The Life—the late 1940s early 1950s American Teenage Drive-in Life was precisely what it was all about—but how could you tell anyone about it? But of course!—the feeling—out here at night, free, with the motor running and the adrenaline flowing, cruising in the neon glories of the new American night—it was very Heaven to be the first wave of the most extraordinary kids in the history of the world—only 15, 16, 17 years old, dressed in the haute couture of pink Oxford shirts, sharp pants, snaky half-inch belts, fast shoes—with all this Straight-6 and V-8 power underneath and all this neon glamour overhead, which somehow tied in with the technological superheroics of the jet, TV, atomic subs, ultrasonics—Postwar American suburbs—glorious world! and the hell with the intellectual bad-mouthers of America's tailfin civilization... They couldn't know what it was like or else they had it cultivated out of them—the feeling—to be very Superkids! the world's first generation of the little devils—feeling immune, beyond calamity. One's parents remembered the sloughing common order, War & Depression—but Superkids knew only the emotional surge of the great payoff, when nothing was common any longer— The Life! A glorious place, a glorious age, I tell you! A very Neon Renaissance—And the myths that actually touched you at that time—not Hercules, Orpheus, Ulysses, and Aeneas—but Superman, Captain Marvel, Batman, The Human Torch, The SubMariner, Captain America, Plastic Man, The Flash—but of course! On Perry Lane, what did they think it was—quaint?—when he talked about the comic-book Superheroes as the honest American myths? It was a fantasy world already, this electropastel world of Mom&Dad&Buddy&Sis in the suburbs. There they go, in the family car, a white Pontiac Bonneville sedan— the family car! —a huge crazy god-awfulpowerful fantasy creature to begin with, 327 horsepower, shaped like twenty-seven nights of lubricious luxury brougham seduction— you're already there, in Fantasyland, so why not move off your smug-harbor quilty-bed dead center and cut loose—go ahead and say it—Shazam!—juice it up to what it's already aching to be: 327,000 horsepower, a whole superhighway long and soaring, screaming on toward ... Edge City, and ultimate fantasies, current and future ... Billy Batson said Shazam! and turned into Captain Marvel. Jay Garrick inhaled an experimental gas in the research lab ...”

Where Does the Value Really Lie?

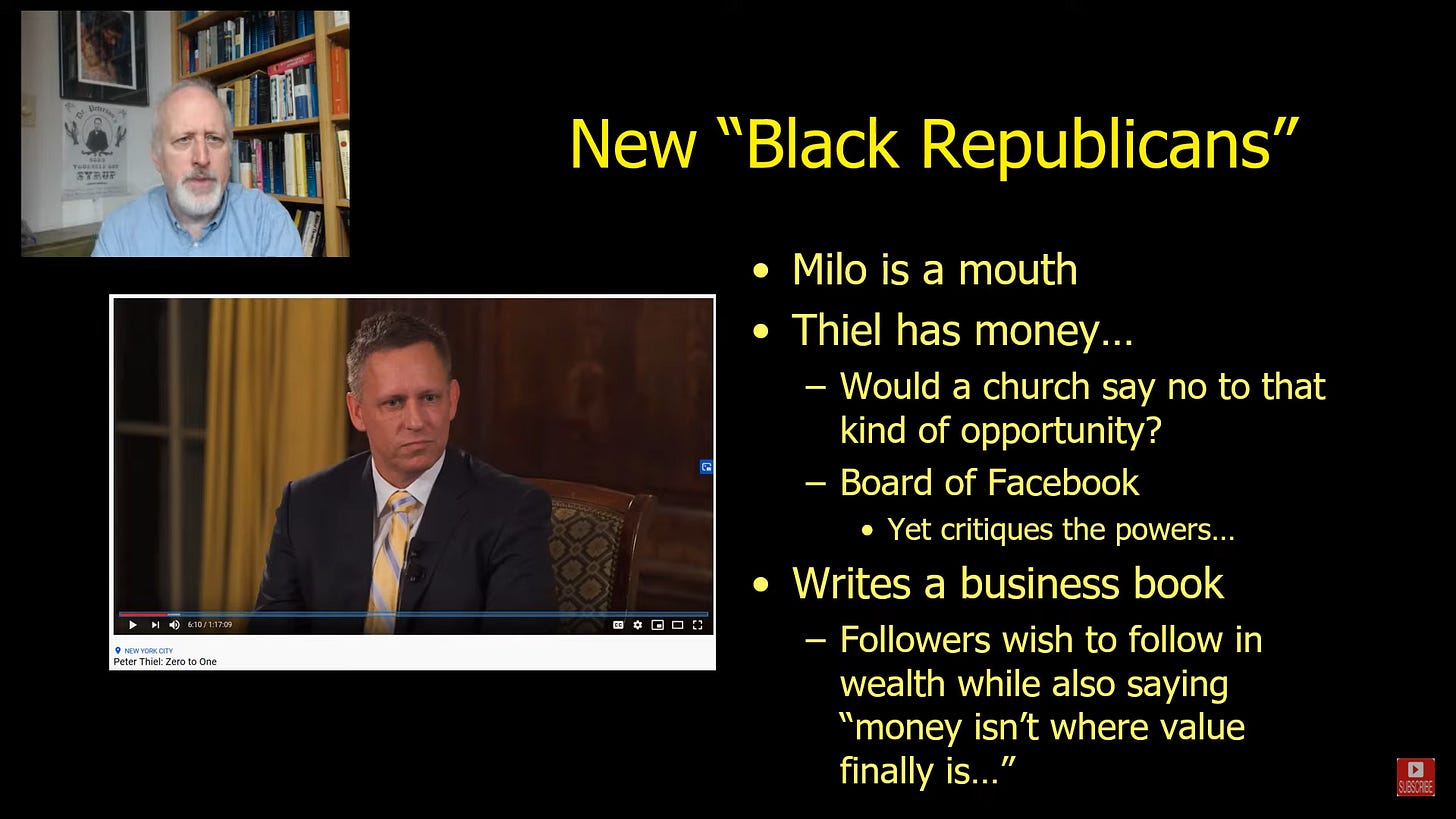

Christian Reformed Church pastor and YouTuber Paul Vander Klay commented on Mr. Thiel in a 2020-era video called “Peter Thiel, Progress, and Religion as the JPEG of Being”:

[Comparing the “New Black Republicans” of gay male conservatives] “Milo is a mouth. Peter, we tend to take much more seriously. Partly because of his money, partly because he’s clearly a much more serious individual. He’s on the Board of Facebook, but what’s interesting about Peter is that there’s some Trumpism about him. What do I mean by that? Not only did he go the Republican convention and endorse Donald Trump from the podium of the convention, and again, his status as a gay man didn’t hurt the Republicans too much. His status as a gay man doesn’t mean Eric Metaxas doesn’t want to talk to him. This is where there’s been a lot of disruption, trying to figure out where the lines are.

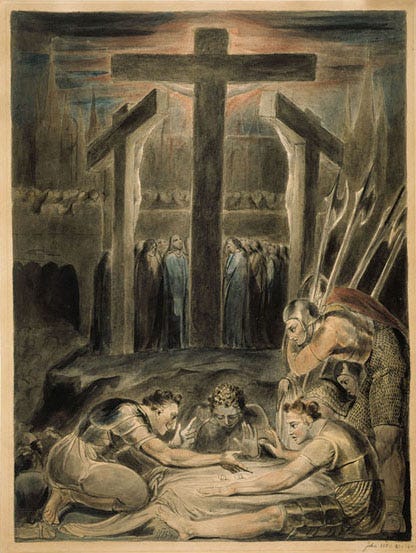

[…] We’re in lands where what is up, and what is down, and what is progress, and what is regress, and what is corruption, and what is decay, and how can we know? And so the member of the Board of Facebook is speaking against the Cathedral, or the Citadel. The Board of Facebook is about as powerful as it gets in certain realms. […] And he wrote a business book. Followers wish to follow in wealth, while saying ‘money isn’t where value finally is…’ So, where is the value? Of course, the most interesting thing in the Douthat-Weinstein video, was the conclusion, where Eric smuggles Jesus in, he brought him right in the front door and says, ‘I can’t help but wonder, if Jesus were alive today, what would happen to him?’ Could Jesus be nullified with the memes? Well, don’t forget, they cast lots, lots, for His clothes. What does that mean? That one garment He wore, which was one long seamless thing, and the soldiers officiating at the execution — crucifixions can take a while — ‘We shouldn’t split this up between us — let’s cast lots.’ Where is the value? Where is the value we recognize?

And the reason Jesus is valued, and the reason wealth in the church is always seen as abdication, and the reason monasteries that said no to wealth and grew fabulously wealthy and then were robbed by the iconoclasts of the Reformation — well, ‘The Five Deaths of the Faith’ in Chesterton’s Everlasting Man. […] Where’s the value? Where is the value? How can we know? Do we follow the money? That will teach you something. Progress: can we know it? Can we see it? Does it look like decadence? Will the pandemic shake us out of it? I don’t know. Why not smuggle Jesus here at the end of this?”

I don’t believe that Pastor Vander Klay had seen Mr. Thiel’s 2013 speech, “You Are Not a Lottery Ticket” when he made this commentary, but he manages to capture exactly the spirit of that speech, which is what I believe is the core of Mr. Thiel’s beliefs. Mr. Thiel may have wealth, but he is ultimately, as I said earlier, a middle-class man, and he seems to believe so much more strongly in economic growth as a result of value creation than he does in the simple generation of cash.

“You Are Not a Lottery Ticket” is Mr. Thiel’s best speech (contra interview), so I recommend watching it in its entirety:

“Money is a means to an end, because there are specific things you want to do with money. In an indefinite world, you have no idea what to do with money, and so money simply becomes an end in itself, which seems always a little bit perverse. You just accumulate money, and you have no idea what to do with it. That seems like a bit of a crazy thing to do, but I think that's actually what what happens a great deal. To illustrate one way that this flow might happen: if you start a successful business, you sell the company or you sell shares to investors in an IPO. You make some money. Question: what do you do with the money? You have no idea, because nobody knows what to do with anything, and so you give the money to a large bank to help you do something. What does the bank do? It has no idea, so it gives the money to a portfolio of institutional investors. What do the institutional investors do? They have no idea, and so they all just invest in a portfolio of stocks. Not too much in any single stock ever, because that suggests you have opinions or you have ideas, and that's very dangerous because it suggests that you're somehow not ‘with it’ and then, what do the companies do that get the money? They've been told that all they should do is generate free cash flows, because if they were to actually invest the money in specific things, that would suggest the companies had ideas about the future, and that would be very dangerous. […]

This is a bit of an extreme picture, but in effect it's a hermetically closed loop, and at the end of the day, no one's doing anything real with the money — it's completely abstracted. […] People actually have no idea what to do with the money. The last big idea people had on what to do with money, that was not sort of circular, was to buy houses and to invest in housing, and that was the idea of the last decade — that idea has gone out of fashion. Now that people no longer want to buy houses, they have absolutely no idea what to do with money. […] There's some sense in which this system of indefinite optimism is gradually running out; there's a way in which the natural drift is for something from finance to insurance. […] There's a way in which Buffett was prescient and ahead of the curve and re-oriented most of his businesses towards insurance companies in disguise which is sort of the world of indefinite pessimism. […] We can sort of see how this indeterminacy affects us in very, very, many different fields. If we look at politics, in an indeterminate world, the most important position in politics is the pollster. What do you do in politics? Nobody has a clue, but what you do is you take a poll, and the polls tell you what to do. They don't really tell you anything on a long-term basis, but they sort of tell you incrementally what you do at any given time, and and as we've tracked towards a more and more indeterminate world, there's a way in which poll-taking has become more and more dominant. And so the way we talk about political campaigns and elections how are people doing in the polls, much more than what ideas they're talking [about]. If Martin Luther King were here, and said, ‘I have a dream about a future that's really different,’ the question would be, ‘How does that poll?’ That's sort of the way we avoid this.”

Anyone who reacts that this speech is evidence that excess money should be redistributed is missing the point here. This is not at all to say that there is no mismatch between the haves and the have-nots, that there are people who can afford to throw away food (and do) and people who have to scrimp and save for every scrap of food they have. That is an undeniable reality. But the point that is made here is that the simple redistribution of money (whether from the newly-minted entrepreneur to the banker or from the same person to the government and back to the single mother struggling to get by) is in and of itself a failure of ideas. We — and the single mothers too and all the too many downtrodden of the Earth — absolutely deserve to live in a society that gives us more than that. Absurdly high quality health care should be stupidly affordable and easy for everyone, food should be nutritious, delicious, and inexpensive, buying a house should be little more investment than buying a car. We can keep shuffling money around from person A to person B to persons Y and Z, crossing our fingers behind our backs that we sure hope the gravy train keeps on a-comin’ as we whistle past the graveyard, or we can start thinking much bigger and do things like invest in prefab houses, 3D printed homes, lab grown meat, urban agriculture, smart mirrors, or AI-assisted depression treatment.

Pastor Vander Klay’s ending comment about the Roman soldiers who cast lots for Christ’s seamless garment at the Crucifixion touches to this point as well. Are we missing the real value that lies before us? Is there a new world, a Heaven, within our arms’ reach that we fail to see because we keep our heads down, whispering under our breath to Lady Luck for something we believe we want but ultimately is meaningless, and we’ve no idea what we’ve given up, of our own narrow vision?

Christian, Deplatonize Thyself

And now, like Pastor Vander Klay, I’ll smuggle in Jesus toward the end here.

Jesus is the ultimate value, but we Christians — who are supposed to profess Him as such — don’t treat Him that way. Nor do we take His words very seriously. Nor do we really believe in Him. Most practicing Christians in America are well-meaning, lovely people, but they are almost all heretics, because they’re secretly Platonists.

Somewhere along the way after the time of Jesus’ ministry here on Earth, Platonism got infused with Christianity, and the Christian flock have been running slightly off-course ever since. St. Augustine didn’t seem to help matters when he tried to crowbar Platonism into Christianity in City of God in the hopes of winning a few more souls. Now, occasionally Christians seem to half-recognize this (but never fully) and react as if in a seizure, which is when we get sadist Puritans burning spinsters while foaming at the mouth, but most of the time, Christians in America function pretty much as neo-Shakers, with more Netflix (or Pureflix, as the case may be) and have a weird relationship in which they participate in the mainstream culture while also being simultaneously disgusted by it, but never really strongly committing to one position or the other or doing very much about anything. Many Christians all but throw their hands up and unconsciously take a really Platonic position that this world is sort of repulsive while also being a source of occasional entertainment, football games, owning the libs, Jesus wouldn’t like that and that, and it’s all screwed up and we just have to live our lives, hang out, go to church on Sunday, roll our eyes at the heathens the rest of the week, entertain ourselves somehow in a way that’s not too morally degenerate, and hold onto some vague bit of two square inches of cultural territory until we die.

Without realizing it, I also held this heretical position before listening to Mr. Thiel over and over again slowly but surely shook me out of it. If you had pressed me before, it’s very possible that I would have made Platonist confessions like, “The world can’t really be fixed,” and “Heaven is a separate state of perfection that can’t be realized here on Earth.” Looking back on it now, I did seem to believe that life as a Christian meant, in my own practice, little more than not being entirely evil and occasionally holding positive feelings toward the Baby Jesus as I sang “Away in a Manger” once a year at a Christmas service. Then, one day, after a relatively comfortable life of enjoyable consumerism in America, I’d die and these actions in my life would be meritorious enough to ensure that I would pass onto the heavenly realm where there is no laundry.

Now I understand that this position is not only Platonist, but actually profoundly anti-Christian because it ultimately denies the Incarnation of Christ. As the philosopher Justin Bieber sang, “Heaven is a place not too far away.” Christ is not some disembodied, spirit-realm god. He came incarnate into this world with our dirty dishes, our messes, our insanely obnoxious leafblowers (maranatha!), our failings, our diseases, our insecurities, our envy, our shame, our manifold sins, and died in this world to redeem all of that — not to obliterate it or discard it but to transfigure it as He Himself was transfigured at Tabor. To be a Christian means to confess that the Bridegroom has come to the Bride, to the Church in this world, and that it is this world over which He has dominion, that is part of His Kingdom. Christians (particularly in the U.S., which affords numerous consumerist luxuries and distractions) have largely abandoned this understanding for this notion that their life here — apart from whatever confession that they make that “Jesus is Lord” for “a ticket to Heaven” after they die — is largely separate from what their experience in the afterlife will be. But this isn’t a correct understanding of Christianity.

Orthodox icon carver and symbolist Jonathan Pageau explains the proper understanding of the Christian’s relationship to Heaven and this world in “Christians Do Not ‘Die and Go to Heaven’”:

“There is a way in which Christians go to Heaven in the sense that there is this ascension, right, this ascension towards that which is above, always this going up the mountain, ascending the divine ladder. So, you can see in all that imagery, this idea of ascending has to do with the notion of going to Heaven. But the problem with when I say, ‘Christians don't go to Heaven,’ it mostly has to do with this idea that people think that ‘You die and you go to Heaven.’ You don't ‘die and go to Heaven.’ […] You're reaching towards Heaven your whole life, you're reaching towards Heaven your whole existence. You're ascending the hierarchy, the spiritual hierarchy of virtues, your whole existence, and so the idea of dying and going to Heaven […] That's not how it works. [...] It’s not because you die that you go to Heaven. Going to Heaven is a transformation of the person, this ascension of the person up [the] levels of the spiritual hierarchy. That’s what ‘going to Heaven’ is.”

Mr. Thiel circles around this conversation very lightly in a talk with Anglican theologian N.T. Wright and New York Times columnist Ross Douthat (and Rev. Wright does seem to be baiting Mr. Thiel several times to talk about Christian Platonism, but Mr. Thiel for some reason I can’t divine doesn’t answer this directly and continues to take the conversation back to “Cartesian duality” on his “atoms and bits” riff). Here, as elsewhere, Mr. Thiel has never gone so far in public as to call out Christian Platonism by name, as far as I am aware, but he does seem to question whether “spiritual interiority” is the end-all-be-all-goal of the Christian life in a talk with Eric Metaxas:

MR. METAXAS: I would argue […] that faith in God is an endlessly self-revealing secret. In other words, that as we pursue God, we are inescapably pursuing a kind of science, because to know God is to become more and more grounded in the reality of His creation, and that those things are related. So, the first question was, why are you hopeful if you think we've given up our sense of wonder, that secrets left to be discovered?

MR. THIEL: Well, I don’t think we’re at the end of history. I don't think we know everything. I certainly refuse to believe that everything has been discovered that's going to be discovered, and I think there are all sorts of contexts where where we can still come to understand new things. Just to push back a little bit — I don't think there's anything wrong with Christian interiority the way you describe it, but I always think it would be somewhat inadequate if it was just that and nothing more. When I was an undergraduate, that sort of the Campus Crusade idea was still [there] — God has a plan for you and for your life and you can figure it out, but then it would translate into a vocation, to something you were supposed to do. We don't talk like that anymore as a culture, not just as Christians. We don't talk like that anymore. It’s much more the sort of pop psychology ala Jordan Peterson or something like that. I think it has to be more than than just psychological.

My own view is that Mr. Thiel may pick up this criticism of Christianity from Friedrich Nietzsche:

“Let us not be ungrateful to it, although it must certainly be conceded that the worst, most durable, and most dangerous of all errors so far was a dogmatist’s error — namely, Plato’s invention of the pure spirit and the good as such. But now that it is overcome, now that Europe is breathing freely again after this nightmare and at least we can enjoy a healthier— sleep, we whose task is wakefulness itself, are the heirs to all that strength when has been fostered by the fight against this error. To be sure, it meant standing truth on her head and denying perspective, the basic condition of all life, when one spoke of spirit and the good as Plato did. […] But the fight against Plato, or to speak more clearly and for ‘the people,’ the fight against the Christian-ecclesiastical pressure of millennia —for Christianity is Platonism for ‘the people’— has created in Europe a magnificent tension of the spirit the like of which had never yet existed on earth.”

— Preface to Beyond Good and Evil (tr. Walter Kaufmann)

Now, Herr Nietzsche had many things to say about Christianity, none particularly positive, but his view that mainstream Christianity as practiced was inherently mass-produced Platonism is correct and he was correct to reject it. Rev. Wright, in his talk with Mr. Thiel, discussed this:

“Nietzsche, quite wrongly, I think, saw Christianity as in his phrase ‘Platonism for the masses’, you know, that this was a way of getting a spirituality that would leave the philosophical academic halls and be available to everyone. I think there was a radical mistake on Nietzsche’s part, because Christianity was never a form of Platonism, because Platonism is precisely a dualistic framework which says that this present world doesn't matter that much, and ideally you inhabit another world already, and you will one day inhabit it completely. That's what people have done with Christianity; to that extent Nietzsche I think was right, but that isn't what original Christianity, Jesus, and Paul, and so on, was all about. I think the task then would be to not to say we agree with Nietzsche’s critique because there are all sort of odd things about it, but to say we need to get back to a more robust holistic heaven and earth together faith and science together way of looking at the world.”

It’s a lovely statement that Rev. Wright says at the end there, and I agree on the face of it (although I believe Mr. Nietzsche deserves a little more credit for calling out correctly the Christianity as it was practiced and discussed in his day and still to this present age) but what is interesting is that Rev. Wright, in his dialogue with Mr. Thiel, still seems to have a Christian Platonist view despite these words. He is manifestly polite and gracious, but he still seems to have a very limited (and boring) view of science and religion as ruddy-cheeked children skipping hand-in-hand through a field of wildflowers and he pushes back (in a very gentle, British way) several times against Mr. Thiel on the question of longevity and immortality:

REV. WRIGHT: I don't see there's anything wrong in saying we could actually increase [lifespan], but the point at which it treads into dangerous territory, it seems to me, would be to imagine a sort of elixir of life as a magic pill, something which sounds rather like what was in the Garden of Eden and wasn't allowed to be taken. […]

MR. THIEL: I don’t want to get into a theological debate here, but I think in the Garden of Eden, if I recall, that there were two trees: it was a Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and they weren't supposed to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The Tree of Life was not forbidden, but it subsequently was. [..] I think there is this question, whether one thinks of death as simply a natural part of life and you know every myth on this planet tells us that, “All that lives must die,” I quote Hamlet's evil mother, and we sort of rationalized death in one form or another. I think the notion that death is unnatural, that it’s sort of fallen or flawed or very screwed up condition which we find ourselves, that's not a pagan view, that is a Christian view.

Christian Platonism isn’t real Christianity, because any Christianity that fundamentally rejects the world in favor of some reasonable consumerist accommodation to it while giving up its redemption altogether in favor of a positive personal experience in a spiritual afterlife is antithetical to the Incarnation of Christ, which is a fundamental and inescapable Christian doctrine. It’s this Christianity which leads to a very slippery slope straight into nihilism and helps enculturate this nihilism around us in our culture, the bitter fruits of which we have daily proof. Christians must return to a real engagement with the world as if it was the personal property of the Savior Himself, which it is, and remember the terrible words of the Just Judge.

It was when I began to deplatonize my own Christianity and realize the meaning, value, and extreme importance of this world that I saw the works of Dr. Girard (which I had read much more fully beyond Google Books in that pandemic phase of going-nowhere-seeing-no-one) in an entirely new light. Dr. Girard pointed to Christ as the One who revealed “the things hidden since the foundation of the world”, the One who came to Earth “to taste our sadness, He whose glories knew no end” and offer us a way out of mimetic rivalry.6 He came to us as the High Priest out of the Holy of Holies at the Rite of Atonement, allowing us to consume Him instead each other, for He was sinless, perfect, immortal, eternally-life giving. I realized that, if we could all just stop tearing each other apart! All the time! and "behave like Christians" as Dr. Girard once said, we could find a very different, much brighter future for ourselves.

Mr. Thiel’s Truth Might Set You Free — If You Let It

My final statement in defense of Mr. Thiel is that I do not believe that he has done all that much in his public life beyond trying to encourage people out of mimetic rivalry and thereby prevent the end of the world, which is as admirable a goal as any in my book. Where everyone gets hung up is on his German demeanor and on his means (i.e., supporting Pres. Trump, regretting that there is less libertarianism in our society), but I’ve yet to see arguments against him that take Mr. Thiel seriously, that assume he has a morally good motive in mind and seek to persuade him and his ‘verse that another approach is superior to reaching what his goals seem to be.

The best example of Mr. Thiel’s efforts is perhaps a guest appearance Mr. Thiel gives in 2019 within the hallowed halls of Harvard University, in a class presumably co-taught by Roberto Unger and Cornel West. Whether he intended to or not, Mr. Thiel’s message almost seems like he has come to try and set the captives free and let them know the door is locked from the inside: