And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

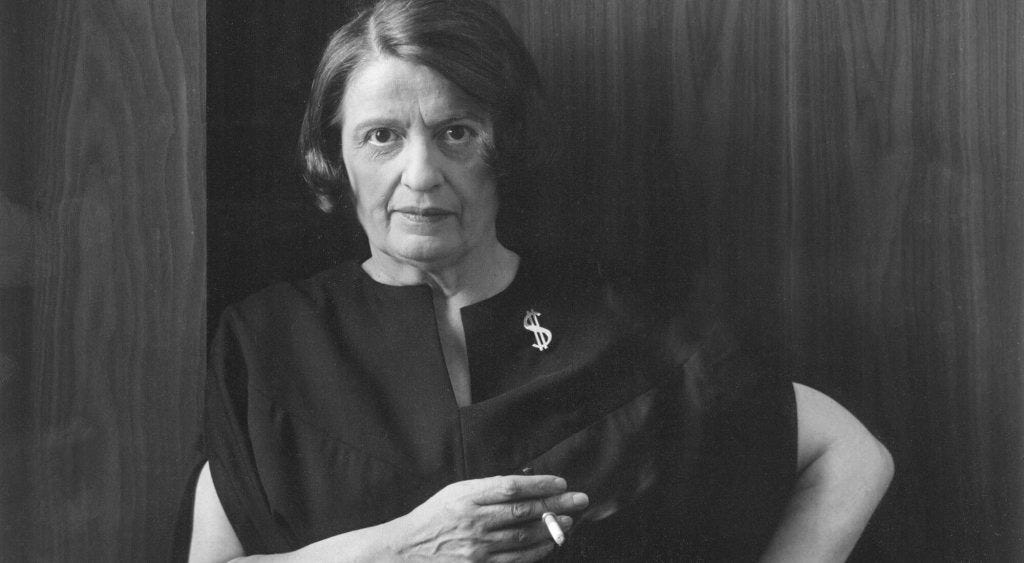

Ayn Rand1 first manifested herself to me by way of a bluestocking high school English teacher — the kind of stern but compelling figure who managed to walk that teacher’s tightrope of commanding both love and fear from her students. Of course, she looked rather a lot like Ayn herself; they could have passed for cousins, if not sisters. I was talking to Ms. N in the hallway (mark the Ms. — like any good English teacher, she was wed to the word, not to a man) before class, and, somewhat out of the blue, she looked at me intently and said, “You should read Atlas Shrugged; it’s by Ayn Rand.” “How do you spell that?” I asked, leaning in closer to hear her over the din. “It’s Ayn,” she said. “A-y-n.” Armed with information, I headed for the fiction section in the bookstore that weekend and picked up a chunky paperback copy of the text printed in a font size apparently targeted at literate ants.

I’ve yet to meet another woman who read Atlas Shrugged at 14, let alone loved it then, so I am left with only my own experience for examination. I’d been a voracious reader practically since I could talk; by fifth grade, I’d devoured the whole of children’s literature and by sixth grade, I’d finished up much of YA and moved on to a diet much heavier on adult fiction, starting with SF&F and historical fiction, and in the rest of middle school I gravitated to doorstoppers like Gone with the Wind, Les Miserables, as well as the whole of the traditional British classics like Jane Austen, Dickens, the Bronte sisters, and Thackery. The relative remoteness of these adult novels, though, in terms of their place in time, were very different, I now realize, than what I experienced when I read Atlas Shrugged. Despite its somewhat alternative history setting, Atlas Shrugged felt contemporary, fresh, immediate, and — especially as I approached it in my early teens — excitingly political. Reading Atlas Shrugged at 14 was like going to a proper, adult dinner party for the first time, snow-white linen tablecloths and fine rooms, wearing makeup and dangling diamond earrings and a dress made not for a girl but for a woman, with Ayn seated next to me, turning to me and asking, in all seriousness, on some present issue of the day — “Well, what do you think?” With Atlas Shrugged, I felt like I had arrived into the adult world, where I was not only allowed but expected to have political awareness, political opinions.

With such an introduction at so delicate a time in my life, I suppose in some sense there was no way, then, not to become totally smitten with Ayn, with her world, with her heroic protagonists. I devoured the whole of her fiction writing within months; by the time I turned to the last page of We the Living, I had developed a hatred for communism as intense as if I myself had endured winters in the U.S.S.R. I committed the singular statement from John Galt’s radio speech as an axiom for my life which I often muttered to myself as I squared my shoulders to walk through the long hallways of my high school in between classes: “I solemnly swear, by my life and my love of it, that I will never live for another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.” Now, I was at this time also a practicing Christian, and one would think that it would have ever occurred to me that this axiom would be at loggerheads with say, the entire ethos of Christianity, but, in fairness to me, I was only a fifteen-year-old girl who’d been raised with the sloppy theology of Anglicanism, which in the present-day form is compatible with pretty much any philosophy you want it to be compatible with.

But as I matured, went to college, found other intellectual pursuits to occupy me, and came more fully to my own in adulthood, Ayn and her world gradually receded into the background. But that never stopped her from coming around to visit me, occasionally — or perhaps it only compelled her, in all her contrarian, oppositional way of being, all the more.

There’s a room in my mind where I think about things, and where I compose pieces of writing in my thoughts; to the extent that I could describe it in physical terms, it’s got dark-paneled walls, lacquered hardwood floors and a high ceiling, and I have a desk in front of the window, which is wide open, where thin white curtains on the side flutter in the breeze. I sit at the desk, writing in my journal, looking out at the bright sky and thinking, and once in a blue, blue, blue moon, Ayn would open the door and slink in. She was always so soft in her approach that I hardly heard her but became suddenly and keenly aware of her presence. I’d turn around to catch her dark-eyed gaze and we’d never say anything to each other, but she always had a kind of maternal love to give me in a way only a Russian Jewish woman could give: she takes an interest and that’s plenty enough.

I never did anything about her occasional appearances, though, besides having the vague thought that I needed to revisit her, somehow, one day, and try to understand whatever to do with her now that I had come well into my adulthood, and then I always set her to the side. But then, she started making herself more forcefully known to me when she came to the surface again, this time in a Peter Thiel interview. Not long after I listened to that interview, I had my first and only (to date) dream about her. I was standing behind a podium in a debate in a conference room in front of an audience — I was arguing that feminism was incompatible with liberalism2 (??) — and as I finished my piece, I went to take my seat in the front row. She was sitting right behind my spot, wearing a smart, bright mustard-yellow pencil skirt and matching blazer which suited her perfectly. I took my seat and then turned around to her to gauge her reaction, and her lips, tinged with a dark burgundy-toned lipstick, broke out into the thinnest but most sincere smile. She gave me a brief, approving nod and I could see a shining light of happiness in her eyes. This minute cluster of reactions from her felt to me in the dream as strong and as validating and as all-encompassing as a standing ovation from a full house at Madison Square Garden. So there was no escaping Ayn, it seemed, and, the next morning as I woke up, the kernel of this post began to take root. She would compel me to reckon with her, after all these years.

On one hand, I obviously feel a great affinity with Ayn: she and I are in some sort of very small category of perhaps autistic, bookish women who are positively disposed toward capitalism and free markets, and appreciate masculine virtues. When I came back to her — or rather, when I accepted her invitation to come back to her — it was like returning to a high school reunion after many decades, seeking out the face of that one person, wondering what one’s own reaction might be — only to discover that all the old feelings come rushing back a thousand times over, strengthened all the more for the long distance in time. And so it was, watching her interviews again, delving back into her world for the first time in eons. I had expected to feel a little bit of cringe for my former affection, that revisiting my adolescent love for her would feel a little suffocating in adulthood, like putting on a once-beloved jacket in a bright, garish color that I’d long since outgrown, both in size and in taste. But it was quite the opposite. I was only re-enchanted by her, coming to realize that my love for her was destined to be everlasting — even knowing all our differences, all her flaws.

For all these strong, positive, almost instinctual feelings of regard for her — there is, on the other hand, a feeling about our relationship, like a scribble of lyrics out of a song by The Cure — from me and you / there’s worlds to part / with aching looks and breaking hearts / and all the prayers your hands can make… She was not, shall we say, a Proverbs 31 woman, much less ever aspired to be one. Ayn was a Nietzschean — as much as Ayn has meant to me, Nietzsche meant a thousand times more to her. So she rather readily adopted, for various reasons I can imagine, his own criticisms against Christianity, and openly rejected the way of life I hold most dear.

That being said, I hold what seems to be — judging by the number of eyebrow raises I get when I bring this up — an extremely fringe, even maybe scandalous, view, which is almost if not entirely anathema to both sets of adherents involved. This view is that Nietzscheanism and Christianity are not as wholly irreconcilable as they might first seem, in a kind of objects-in-mirror-are-closer-than-they-might-appear sort of way.3 I will try to explain my arguments in more depth at another time, but for now, this post is my effort to sketch this out in some small way, not out of some gratuitous intellectual exercise — but out of a personal conviction, a need even, to lay down something of a bridge between me and her, and thereby to try and cross those waters that lie between us in these “worlds to part”.

This is for you, Ayn. Come back by anytime. The door’s open.

Can Nature Be A Standard?

We will begin, then, with the creation of the world and with God its Maker, for the first fact that you must grasp is this: the renewal of creation has been wrought by the Self-same Word Who made it in the beginning. There is thus no inconsistency between creation and salvation; for the One Father has employed the same Agent for both works, effecting the salvation of the world through the same Word Who made it at first.

— St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation

It was not long after listening to this this discussion that Alex Epstein had with Peter Thiel last summer that Ayn came back to me in the dream. Mr. Epstein and Mr. Thiel’s discussion was framed around Mr. Thiel challenging various points in Mr. Epstein’s book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas–Not Less. While I am largely unfamiliar with Mr. Epstein, as far as I can tell he seems to be a dyed-in-the-wool Randian, having worked at the Ayn Rand Institute before he founded the Center for Industrial Progress (a Randian name if ever I heard one!). At one point in the discussion, noted below, Mr. Thiel says to Mr. Epstein that he understands him as an “unreconstructed Randian”, a point which Mr. Epstein largely does not dispute.

Now, on the other hand, I have never heard Mr. Thiel deeply discuss his thoughts on Randianism or the philosophy Mrs. Rand developed, Objectivism, although it seems he has surely read at least one of her seminal novels, The Fountainhead. In 2021, he accepted a lifetime achievement award from the Atlas Society, an explicitly Randian organization. Certainly, Mr. Thiel and the Randians seem to run in similar circles of thought, especially with respect to the monetary system (as I have touched on very briefly here in the introduction to this piece). What is so particularly interesting about this discussion, however, is that beneath the first layer of conversation about environmentalism and energy policy — the bread and butter of Mr. Epstein’s work — is an extremely fascinating, even if much less overt, conversation between a Randian and a Christian about the meaning of nature and the human being.

At one point in the conversation, this break between Mr. Thiel’s perspective and Mr. Epstein’s becomes most clear, and while Mr. Thiel never references Christianity or Christian principles directly in this discussion, he seems to be fashioning an argument that implicitly assumes them (transcript lightly edited for clarity):

MR. THIEL: One philosophical question. You're sort of a unreconstructed Ayn Randian-type person — or almost unreconstructed?

MR. EPSTEIN: Yes.

MR. THIEL: And so human nature is actually not that strong; it's not that well defined, the way I understand the Randian view. It's sort of like it's a very abstract thing, you're a human being; maybe a self-creating being, or something like that, but it's not like some Thomistic set of things that precisely define human nature. So, what do you, as a Randian, mean by human nature?

MR. EPSTEIN: Well, I'll tell you what I mean, but I'm not sure what the contrast is. You're saying it's determined versus not?

MR. THIEL: Well, I'm always a little bit nervous with nature as the standard that we measure things by. What does it actually tell us and especially vis-a-vis human beings? Maybe there's some natural standard of how the laws of nature work: you don't have to fly, because it violates the law of gravity if you don't have wings. There’s all sorts of ways one can use it — but I don't know how one uses nature as a standard with respect to human beings.

MR. EPSTEIN: Well, it’s not a standard.

MR. THIEL: It's supposed to have some normative force in the way in which you're using it, or is it?

MR. EPSTEIN: Well, it has normative force in that it tells you specifically about the causal relationships that you need to understand to achieve some outcome, right? If you understand the nature of life is such that you have to transform nature to meet your needs — which is really the heart of productivity — that tells you that productivity is innate, is a virtue, if your goal is for human beings to flourish.

MR. THIEL: But then, why shouldn’t we just make productivity the standard — or GDP the standard?

MR. EPSTEIN: Well, this goes to the holistic thing of it. I said it's a crucial virtue but there's a question of what if the end is a happy life or flourishing life? The idea is there are multiple necessary causal inputs in that and the other way in which you study nature is, you sort of understand the nature of the being you are including how happiness works, how emotions work, etc. In terms of the Randian Objectivist view, I think she's good at not claiming to understand every aspect of human nature. Her philosophy is focused on certain essentials that then other fields will work with. So, for example, reason is man's basic tool of survival. That's a key aspect of nature: reason is volitional, which — that's a more controversial issue — human beings actually have choice. Then there's an account of what is the nature of choice versus what's not. Even something like political, like freedom, is the social precondition for exercising reason, but it's trying to identify these universal, timeless fundamentals that we can then use to discover other things. […]

MR. THIEL: There's a part of me that is very sympathetic to that, and then part of me that gets very nervous about it, because my look-ahead function is immediately to what does this mean for public policy, politics, etc. On an individual level, I would agree that if human beings are more rational at the margins, they're likely to be happier and have more flourishing lives, and they have some control over that, some freedom to choose, to live more rational lives, and that all sounds good to me. As soon as we say, “Well, maybe the state should help people be a little bit more rational,” we're on the road to North Korea, and so the framing —

MR. EPSTEIN: Right, but then — I don't want to just focus on her, but people can read “What Is Capitalism?” in the book Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, that's her most fundamental thing on capitalism. [...]

MR. THIEL: Let me go back to the question: How does human flourishing do? If it's just something that obviously makes sense on an individual level, that's good. If it's a standard for policy makers, that feels fuzzy, and therefore dangerous to me. If you're appealing to people's rational self-interest, and you want to have a flourishing life, and it's your power to do that you know a la Jordan Peterson and this is your approach to self-help, that's all good; it's better than Jordan Peterson. If you're in the EPA and, “Did you know you’re in charge of human flourishing”, right? — this is a formula for mischief.

MR. EPSTEIN: Really glad you brought this up, because this is a really important thing. So, when I'm talking about human flourishing as a basis for policy, I think it's overwhelmingly in the realm of what we can call environmental policy. Take the example if we're thinking about something like air pollution, because I believe in rights-based framework for all this stuff, but in defining like what level of pollution violates a right or not, ultimately the way to determine that is to think about life in a holistic way, in terms of, “What's going to lead to human flourishing?” You're defining the rights to say, “This is a level of this pollution; this is what constitutes trespassing on your neighbor versus not.” You're sort of deriving the rights from an understanding of human flourishing, but you recognize that the key to individual flourishing is is freedom of action within defined spheres, so the last thing you want is some dictator who arbitrarily gets to say on a case-by-case level, “Oh, this is what you need to flourish; this is what you need to flourish.” I think the the concept of human flourishing is used in the determination of rights in these kinds of environmental issues. The other way in which I think it's important, is insofar as we're broadly debating across different political philosophies what to do about energy, I think for every political philosophy is a question of, are you looking at it from a pro-human way or an anti-human way? And whatever your political philosophy is, even if you're collectivist, you should be looking at it in a pro-human way.

[…]

MR. THIEL: Let me ask about one ambiguity there. Is human flourishing about human beings, individually, or human beings, collectively?

MR. EPSTEIN: I don't think — I don't make a separation.

MR. THIEL: I think in theory, there's no separation, but in practice I would argue there is, because if you look at them individually you would probably focus on the human beings currently in existence, whereas if you think about them collectively, there's some version where you get into thinking about all the human beings from now till the year 3000 and beyond, and in theory, that's a more holistic perspective. I hate EA, and in practice, it's a formula for endless mischief…

MR. EPSTEIN: I'm happy to talk about it, but I'm also not utilitarian. […] Let's put it through the anti-impact movement — taken literally and seriously, it is the ultimate form of human sacrifice because, it's basically saying, “Sacrifice for the sake of an unimpacted planet,” whereas you have all these other seemingly pro-human things that end up being anti-human. […] Like, that's not my version at all. But then Peter Singer — effective altruist — his alleged genius contribution was to bring in all of these other animals that we actually can't peacefully coexist with, and say, "Well we should factor in their ‘happiness’ versus human beings we can beneficially coexist with, so respecting their rights is good for us.” So he's done that, and now he's part of this movement to consider the imagined interest of humans indefinitely into the future and what this all leads to is just an unlimited license to sacrifice individuals, and to consider their lives unimportant and their rights non-existent. You look at like a MacAskill4 type, I mean, their thinking is such crap, if you know about any of the issues on some level.

MR. THIEL: You’re being way too kind to these people. I find it hard to even think that they're acting in good faith. It’s like some attempt to go towards some weird ad hominem sociological commentary where if we have some capitalist-communist fusion product that's very desirable in our society, where someone like Sam Bankman-Fried says he's going to be the world's first trillionaire and it's okay because he's an effective altruist; he's going to give everybody on the planet a hundred dollars. Then there is a theoretical discussion about whether this is a good way to build the future and morally correct, and I can't even get to that, because I just don't believe any of it. I just think it was all a fraud — but you're the better person.

MR. EPSTEIN: But by the way if people are interested in this — if you search “Ayn Rand Institute effective altruism” — I used to work there and some of my colleagues have talked about this; I think they have some good stuff. What I do need to distinguish myself from is all the forms of human sacrifice, of individual sacrifice, that masquerade as a kind of collective, including future collective, human flourishing. That is a battle that needs to be fought; it's not my primary battle because my primary battle is against people who want to sacrifice human flourishing to unimpacted nature.

[…]

MR. EPSTEIN: Can you talk briefly about the need for a positive vision — and let's focus in particular on my issue on energy and Industry — because I want to hear you talk about that and see if we differ at all and see if I can learn anything?

MR. THIEL: If we're going to have a 21st century that is successful, I think it will somehow look different in a physical material way from the 20th century. The energy version would be that it would physically look different. My intuition is that we have, I don't know, maybe lots of forests and a few nuclear power plants that power the whole the whole country, versus we've chopped down all the trees and covered them with solar panels that barely work, or something like this, or, you know, we have windmills polluting the entire coast and ugilfying the landscape. But there's sort of like a picture of what our society, what the future looks like, and we're hesitant to push too specific a picture, because we're not in favor of centralized government. We don't want to dictate this or something like that um and uh and at the same time I think this is one of the weaknesses on our side: we don't have a of a a concrete picture of how this different world will look like and then the other side surely does. […]

If Los Angeles looks exactly like the present in 2100, I think we will have somehow failed in a various way. Then, the green people would tell us if it looks exactly like this, that's the best we can hope for: that if all just grew over. […] I keep coming back to: it shouldn't be abstracted. It's not just the rhetoric. It's not just the abstract, right, and if we could actually have a picture, this is good. One of the things that's been a little bit weak about the information age revolution in Silicon Valley is that it’s a little bit too abstracted from the physical layer. Yes, AI and the large language models: it's a very big technological breakthrough; it will make a very big difference. Then, I don't think that's the only dimension in which the future should look different from the present. It can't just be the level of bits. It has to also be on the level of atoms.

Nestled within this conversation are several interesting questions about how Randianism intersects with Christian values — even while explicitly rejecting them — especially on the question of human beings and our relationship to nature. But ultimately, all of these questions and comments have very modern assumptions underneath them that cannot go unexamined. To understand the modern relationship with nature, however, we must first revisit the past.

“Mystics Of Spirit Or Mystics Of Muscle — Reason? Whoever Heard Of It?”

As I went back into the Randian world for this post, I came across an interesting piece from 2013 in First Things: “Ayn Rand Really, Really Hated C.S. Lewis”, which highlights Ayn’s marginalia on her copy of C.S. Lewis’ 1943 compilation of lectures stitched together in one of his more known works, The Abolition of Man. I found Ayn’s marginalia to be: (1) really very funny; and (2) really rather unsurprising. Ayn held a modernist’s view of the world and Mr. Lewis a medieval one5. Modernists and medievalists have been at each other’s throats since scholasticism.

A passage in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber (below, tr. Talcott Parsons) crisply explains the differences between the medievalist and the modernist (here, little different than the Calvinist — appropriate, as Ayn shares quite a bit with Calvinism6):

Although the Reformation is unthinkable without Luther’s own personal religious development, and was spiritually long influenced by his personality, without Calvinism his work could not have had permanent concrete success. Nevertheless, the reason for this common repugnance of Catholics and Lutherans lies, at least partly, in the ethical peculiarities of Calvinism. A purely superficial glance shows that there is here quite a different relationship between the religious life and earthly activity than in either Catholicism or Lutheranism. Even in literature motivated purely by religious factors that is evident. Take for instance, the end of the end of the Divine Comedy, where the poet in Paradise stands speechless in his passive contemplation of the secrets of God, and compare it with the poem which has come to be called the Divine Comedy of Puritanism. Milton closes the last song of Paradise Lost after describing the expulsion from paradise as follows: —

“They, looking back, all the eastern side beheld

Of paradise, so late their happy seat,

Waved over by that flaming brand; the gate

With dreadful faces thronged and fiery arms.

Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon:

The world was all before them, there to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide.”And only a little before Michael had said to Adam:

. . . “Only add

Deeds to thy knowledge answerable; add faith;

Add virtue, patience, temperance; add love,

By name to come called Charity, the soul

Of all the rest: then wilt thou not be loth

To leave this Paradise, but shall possess

A paradise within thee, happier far.”One feels at once that this powerful expression of the Puritan’s serious attention to this world, his acceptance of his life in the world as a task, could not possibly have come from the pen of a medieval writer.”

Ayn revolted against passages like these in The Abolition of Man:

“The fact that the scientist has succeeded where the magician failed has put such a wide contrast between them in popular thought that the real story of the birth of Science is misunderstood. You will even find people who write about the sixteenth century as if Magic were a medieval survival and science the new thing that acme in to sweep it away. Those who have studied the period know better. There was very little magic in the Middle Age: the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at the high noon of magic. The serious magical endeavour and the serious scientific endeavor are twins: one was sickly and died, the other strong and throve. But they were twins. They were born of the same impulse. I allow that some (certainly not all) of the early scientists were actuated by a pure love of knowledge. but if we consider the temper of that age as a whole we can discern the impulse of which I speak. There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the ‘wisdom’ of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique; and both, in the practice of this technique, are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disguising and impious — such as digging up and mutilating the dead. […]

It might be going to far to say that the modern scientific movement was tainted from its birth: but I think it would be true to say it was born in an unhealthy neighbourhood and at an inauspicious hour.”

Contra Mr. Lewis, Ayn wrote in The New Left, lauding, against the “mystics of spirit or mystics of muscle”, the birth of reason:

The Middle Ages were an era of mysticism, ruled by blind faith and blind obedience to the dogma that faith is superior to reason. The Renaissance was specifically the rebirth of reason, the liberation of man’s mind, the triumph of rationality over mysticism— a faltering, incomplete, but impassioned triumph that led to the birth of science, of individualism, of freedom.

Mr. Lewis’ perspective in The Abolition of Man is quite an interesting foil to Ayn, and it is little wonder that The Abolition of Man stirred up such passion in her, because, strangely enough, the arguments that Mr. Lewis — one of the most famous Christians in the 20th century Anglosphere — presents in The Abolition of Man are not only not particularly Christian: they are even — perhaps — somewhat antithetical to it. And Ayn, being extremely modern, might have found herself making, without knowing it, quite Christian objections. Where The Abolition of Man really falls apart as any sort of reasonable Christian apologia that Christians could offer to a modern like Ayn, however, is with respect to the subject of the discussion between Messrs. Thiel and Epstein: on man’s relationship to nature.

In The Abolition of Man:

Now I take it that when we understand a thing analytically and then dominate and use it for our convenience we reduce it to the level of “Nature” in the sense that we suspend our judgments of value about it, ignore its final cause (if any), and treat it in terms of quantity. This repression of elements in what would otherwise by our total reaction to it is sometimes very noticeable and even painful: something has to be overcome before we can cut up a dead man or a live animal in a dissecting room. These objects resist the movement of the mind whereby we thrust them into the world of mere nature. But in other instances too, a similar price is exacted for our analytical knowledge and manipulative power, even if we have ceased to count it. We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams: the first man who did so many have felt the price keenly, and the bleeding trees in Virgil and Spenser may be far-off echoes of that primeval sense of impiety. The stars lost their divinity as astronomy developed, and the Dying God has no place in chemical agriculture. […]

We reduce things to mere Nature in order that we may “conquer” them. We are always conquering Nature, because “Nature” is the name for what we have, to some extent, conquered. The price of conquest is to treat a thing as mere Nature. Every conquest over Nature increase her domain. The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them: the soul does not become Nature till we can psycho-analyse her. The wrestling (wresting) of powers from nature is is also the surrendering of things to Nature.

The Western medieval project was to slowly integrate the pagan world into the Christian one, and it is such a pre-modern worldview that Mr. Lewis presents here, where artifacts of paganism remain in the presence of “bleeding trees” or otherwise the stars have “divinity”. It is no surprise that Mr. Lewis holds such a perspective, as it is the exact same perspective that very much informs his seminal work of fiction, his children’s series The Chronicles of Narnia. In Narnia, four human children from wartime London enter into a magical world populated not only by ordinary (albeit talking) animals like beavers and horses, but also mythical creatures such as fauns, centaurs, satyrs, unicorns, dwarves, giants, and of course, Mr. Lewis’ favorite dryads.

Jonathan Pageau noted this in some comments on the Narnia series:

C.S. Lewis, unlike Tolkien, does not take into account the quality of the beings he places into his Narnia. For example, a satyr has a certain characteristic. It’s a human with animal legs. Centaurs are usually related to aggressive, out-of-control sexual desire. To have them be characters in the book, like, ‘Here’s the centaur, here’s the faun, here’s all these creatures,’ and they don’t have the qualities of what they are?

One important purpose of myth is to provide information, a kind of map, about the wider world. Almost all mythical creatures represent an exaggerated version of marginalia that a person would encounter as they leave the domain of their known world. In some cases, such as with dwarves or giants, these mythical apprehensions are simply intended to demonstrate exaggerated differences in height relative to a native population — if the hero leaves his home and wanders out far enough into populations that have not genetically mixed in with his own, he will find people who look very different from him. Similarly, mythical tropes are rife with siren-like temptresses of one sort or another, women who are beautiful and unusually available, always with some sort of catch that is not immediately clear, and these tropes are simply intended to explain how foreign women encountered in the margins of one’s world will be especially appealing because of their novelty, but nonetheless are dangerous because they are from cultures with which the hero may have little familiarity, and to fall into any sort of relationship with such women may bind the hero to the foreign world in ways he does not anticipate.

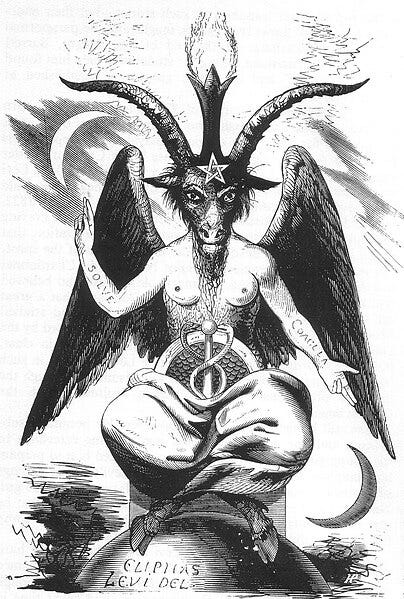

The monsters, however, that Mr. Lewis includes in Narnia, are a distinct expression of myth, beyond simple information about marginalia. These are either animal hybrids or, more strikingly, half-human, half-animal hybrids: fauns, satyrs, centaurs. Monsters are notable, and their treatment in stories very important, because they are what is ultimately generated at the end of mimetic frenzy. For a Shakespearean example, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the play-within-a-play actor Nick Bottom mutates into a human with an ass’ head — concurrent with the mimetic crisis undergone by the wilds of the forest by the four entangled lovers who frame the story. René Girard explains in A Theater of Envy:

If the lopsided view that the lovers take of their own relations keep reversing itself at a constantly accelerated pace, the moment must come when all differences oscillate so rapidly that a separate and distinct apprehension of the polarities they define becomes impossible; all extremes contaminate each other. Beyond a certain threshold of instability, dizziness prevails and normal vision is impaired; hallucinations occur, but not of an an entirely capricious and imaginary type.

When the dog and the god, the beast and the angel, and all such contraries oscillate fast enough, they become one, but not in the sense of some harmonious “synthesis” à la Hegel. Entities are beginning to merge that will never truly belong together; the result is a jumble of bits and pieces borrowed from the component beings. If an illusion of unity emerges, it will include fragments of the former opposites arranged in a disorderly mosaic. Instead of a god and a dog facing each other as two irreducible specificities, we will have changing combinations and mixtures, a god with beastlike features, or a beast that resembles a god. This process is properly cinematic. When many images are seen in quick succession, they produce the illusion of a single moving image, the appearance of a living being that seems more or less one, but in this case it will have the form, or rather the formlessness, of “some monstrous shape.”

A mythical monster is a conjunction of elements normally specific to different creatures; it will automatically result from the process suggested by Shakespeare, if the substitutions are numerous and rapid enough to become imperceptible as such. IN a centaur, elements specific to a horse and a human being are joined, just as elements specific to an ass and a human being are joined in the monstrous metamorphosis of Bottom. Since there is no limit to the differences that can be jumbled together, the diversity of monsters will seem infinite and will seem to “marry” one another. The “seething brain” of a Bottom is about to transform this metaphoric marriage into a real one, his own, with the queen of the fairies herself, the beautiful Titania.

The playwright does not merely invite us to witness the gracious but insignificant evolution of purely decorative fairies; he offers us a coherent view of mythical genesis. The fairies are “monsters,” and Bottom becomes one as well when he turns into an ass. Monsters are a conjunction of man, god, and beast, and are born as a result of the process triggered by the use and abuse of animal and transcendental images. [….] [F]or Shakespeare himself, the monstrous metamorphosis of Bottom is rooted in mimetic interaction via the animal images. The “supernatural” incidents of the play are not the gratuitous fabrication of an author different to the intellectual unity of his work. The myth of the fairies is a production of the people overcome by mimetic frenzy. […] The monster is the last phase before a confusion so total that everything becomes alike.”

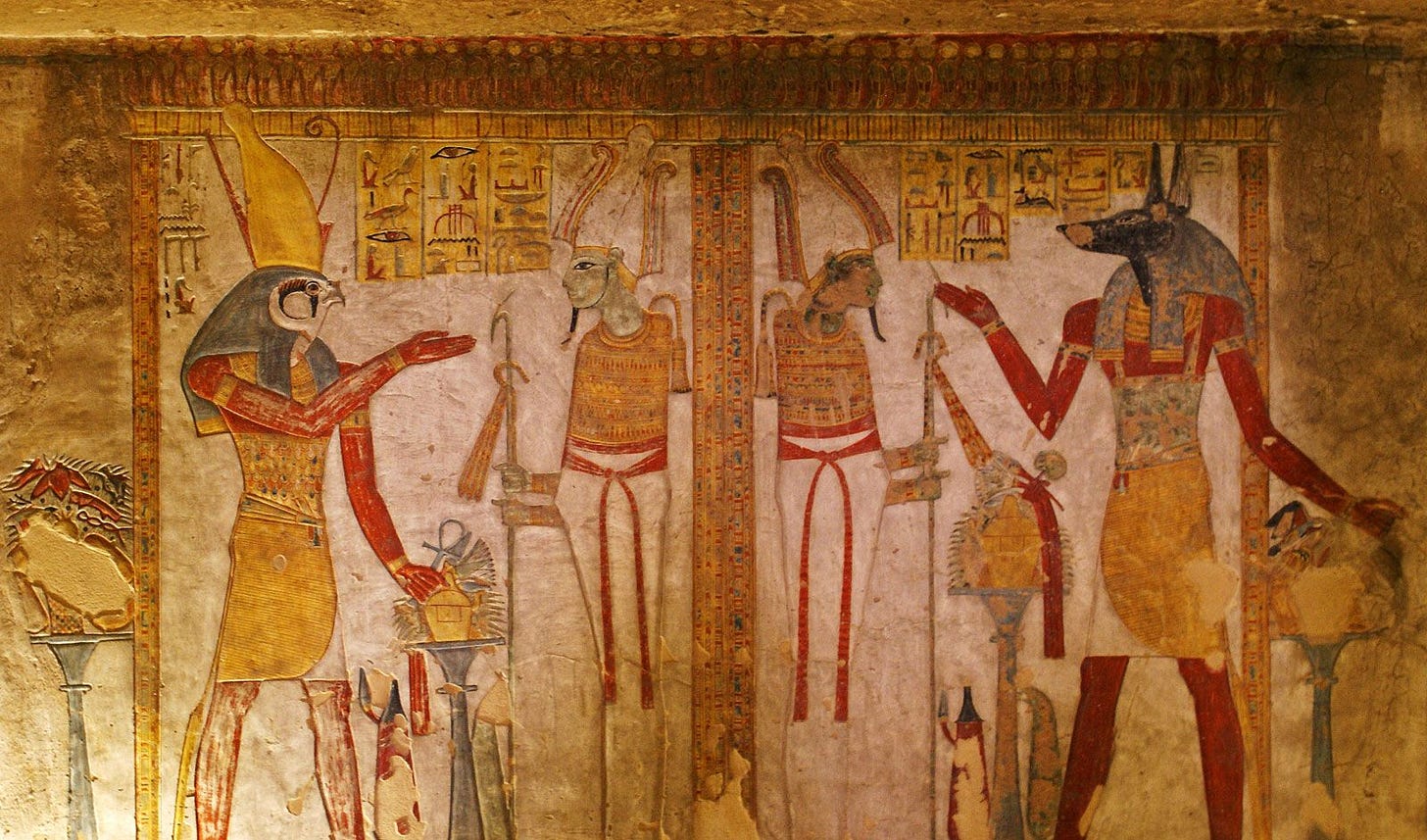

That monsters are so associated with mimetic frenzy (and, ultimately, a murder to resolve the tension) gives rise to their prevalence in paganism, as pagan religions are simply capturing (and thus attempting to control) the symbols that they see emerge in mimetic crises, where the monster becomes a god because he unifies the community. The ancient Egyptians perhaps documented this best:

And, more famously:

In the Narnia universe, almost all the monsters serve the lion Aslan, the allegorical stand-in for Christ and putative theocratic ruler of Narnia, which is an interesting choice indeed as Mr. Pageau suggests, because the monsters are fundamentally representing very pagan concepts that are inherently linked with human sacrifice. This is perhaps the clearest example of the flawed reasoning that underlies Mr. Lewis’ arguments in The Abolition of Man.

Stranger still, The Abolition of Man, composed a good decade after Mr. Lewis’ conversion to Christianity, scarcely references Jesus Christ at all, and, even worse, for reasons I can only hazard a guess at, serves up the same exact warmed-over perennialism for which Christians have verbally flogged Aldous Huxley — who was never a professing Christian — for eighty years.

Instead of leaning his arguments on Jesus Christ, Mr. Lewis rests the bulk of The Abolition of Man upon what he calls the “Tao”:

The Chinese also speak of a great thing (the greatest thing) called the Tao. It is the reality beyond all predicates, the abyss that was before the Creator Himself. It is Nature, it is the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time. It is also the way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar. […] This conception in all its forms, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Christian, and Oriental alike, I shall henceforth refer to for brevity simply as: the Tao.

Later:

And is it, in any event, possible to talk of obeying what I call the Tao? If we lump together, as I have done, the traditional moralities of East and West, the Christian, the Pagan, and the Jew, shall we not find many contradictions and some absurdities? I admit all this. Some criticism, some removal of contradictions, even some real development, is required. […]

[T]he Tao admits development from within. There is a difference between a real moral advance and a mere innovation. From the Confucian “Do not do to others what you would not like them to do to you” to the Christian “Do as you would be done by” is a real advance. The morality of Nietzsche is a mere innovation. The first is an advance because no one who did not admit the validity of the old maxim could see reason for accepting the new one, and anyone who accepted the old would at once recognize the new as an extension of the same principle. If he rejected it, he would have to reject it as a superfluity, something that went too far, not as something simply heterogenous from his own ideas of value. The Nietzschean ethic can be accepted only if we are ready to scrap traditional morals as a mere error and then to put ourselves in a position where we can find no ground for any value judgements at all.

The concept of the Tao is integral to the arguments in The Abolition of Man. What Lewis is trying to conceptualize as “the Tao” is some sort of natural law, a roughly similar code of ethics that continually emerges across many different cultures and at many different periods in history.7 This is further reinforced by the absolutely appalling appendix to The Abolition of Man, titled “Illustrations of the Tao”, which he introduces with the following commentary:

The following illustrations of the Natural Law are collected from such sources as come readily to the hand of one who is not a professional historian. The list makes no pretence of completeness. It will be noticed that writers such as Locke and Hooker, who wrote within the Christian tradition, are quoted side by side with the New Testament. This would, of course, be absurd if I were trying to collect independent testimonies to the Tao. But (1) I am not trying to prove its validity by the argument from common consent. Its validity cannot be deduced. For those who do not perceive its rationality, even universal consent could not prove it. (2) The idea of collecting independent testimonies presupposes that ‘civilizations’ have arisen in the world independently of one another. […[ It is by no means certain that there has ever (in the sense required) been more than one civilization in all history. It is at least arguable that every civilization we find has been derived from another civilization, and in the last resort, from a single center— “carried” like an infectious disease or like the Apostolic succession.

Mr. Lewis then goes on to list, in a kind of tossed-together kleptomaniac salad to make the British Museum blush, his “illustrations” in axioms from the Laws of Manu, Babylonian hymns, Exodus, Cicero, old Norse, Homer, 1 Timothy, ancient Egyptian confessions, Native American accounts, observations of the Australian Aborgines, Beowulf, Seneca, the Bhagavad gita, Plato, and the Gospel of John.

Mr. Lewis correctly notes in his illustration that “those who do not perceive its rationality, even universal consent could not prove it” because there is no rationality to be perceived here. To sprinkle together the words of the Lord from the Gospel of John with Old Norse and Seneca is an undertaking that even the leftist libertine Thomas Jefferson did not dare do.

Ultimately, Mr. Lewis uses the concept of the Tao to develop the idea of a universal “law of nature”, here expressed in his most famous work of nonfiction, Mere Christianity:

Now this Law or Rule about Right and Wrong used to be called the Law of Nature. […] But when the older thinkers called the Law of Right and Wrong "the Law of Nature," they really meant the Law of Human Nature. […]

This law was called the Law of Nature because people thought that every one knew it by nature and did not need to be taught it. They did not mean, of course, that you might not find an odd individual here and there who did not know it, just as you find a few people who are colour-blind or have no ear for a tune. But taking the race as a whole, they thought that the human idea of decent behaviour was obvious to every one. And I believe they were right. […]

I know that some people say the idea of a Law of Nature or decent behaviour known to all men is unsound, because different civilisations and different ages have had quite different moralities.

But this is not true. There have been differences between their moralities, but these have never amounted to anything like a total difference. If anyone will take the trouble to compare the moral teaching of, say, the ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, Hindus, Chinese, Greeks and Romans, what will really strike him will be how very like they are to each other and to our own. Some of the evidence for this I have put together in the appendix of another book called The Abolition of Man [….]”

To Mr. Lewis, theistic pagans have a moral teaching "like […] to our own” (that is, Mr. Lewis’ own Christianity). Because Mr. Lewis has the typical literate hangover common to all moderns, he myopically focuses on stripping down whole cultures to what has been written down — totally ignoring ritual and all that lies before literacy, much less before language — and considers this much more of a whole summation of a Weltanschaaung than it actually is. It is especially absurd that Mr. Lewis, as a Christian, would include the Babylonians in this list as having a “moral teaching” similar to “our own”, given that he should have been well familiar with the story of Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego in the Book of Daniel:

King Nebuchadnezzar made an image of gold, sixty cubits high and six cubits wide, and set it up on the plain of Dura in the province of Babylon. He then summoned the satraps, prefects, governors, advisers, treasurers, judges, magistrates and all the other provincial officials to come to the dedication of the image he had set up. So the satraps, prefects, governors, advisers, treasurers, judges, magistrates and all the other provincial officials assembled for the dedication of the image that King Nebuchadnezzar had set up, and they stood before it.

Then the herald loudly proclaimed, “Nations and peoples of every language, this is what you are commanded to do: As soon as you hear the sound of the horn, flute, zither, lyre, harp, pipe and all kinds of music, you must fall down and worship the image of gold that King Nebuchadnezzar has set up. Whoever does not fall down and worship will immediately be thrown into a blazing furnace.”

Therefore, as soon as they heard the sound of the horn, flute, zither, lyre, harp and all kinds of music, all the nations and peoples of every language fell down and worshiped the image of gold that King Nebuchadnezzar had set up.

At this time some astrologers came forward and denounced the Jews. They said to King Nebuchadnezzar, “May the king live forever! Your Majesty has issued a decree that everyone who hears the sound of the horn, flute, zither, lyre, harp, pipe and all kinds of music must fall down and worship the image of gold, and that whoever does not fall down and worship will be thrown into a blazing furnace. But there are some Jews whom you have set over the affairs of the province of Babylon—Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego—who pay no attention to you, Your Majesty. They neither serve your gods nor worship the image of gold you have set up.”

Furious with rage, Nebuchadnezzar summoned Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego. So these men were brought before the king, and Nebuchadnezzar said to them, “Is it true, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, that you do not serve my gods or worship the image of gold I have set up? Now when you hear the sound of the horn, flute, zither, lyre, harp, pipe and all kinds of music, if you are ready to fall down and worship the image I made, very good. But if you do not worship it, you will be thrown immediately into a blazing furnace. Then what god will be able to rescue you from my hand?”

Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego replied to him, “King Nebuchadnezzar, we do not need to defend ourselves before you in this matter. If we are thrown into the blazing furnace, the God we serve is able to deliver us from it, and he will deliver us[c] from Your Majesty’s hand. But even if he does not, we want you to know, Your Majesty, that we will not serve your gods or worship the image of gold you have set up.”

Then Nebuchadnezzar was furious with Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, and his attitude toward them changed. He ordered the furnace heated seven times hotter than usual and commanded some of the strongest soldiers in his army to tie up Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego and throw them into the blazing furnace. So these men, wearing their robes, trousers, turbans and other clothes, were bound and thrown into the blazing furnace. The king’s command was so urgent and the furnace so hot that the flames of the fire killed the soldiers who took up Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, and these three men, firmly tied, fell into the blazing furnace.

What is dearly missing from this story, one will observe, is any sort of “moral teaching” that compels King Nebuchadnezzar to stop the human sacrifice of three young men, strangers in their midst. Nor does he even have the slightest compunction about killing three young men on the basis that they will not engage in pagan worship. On the contrary: he is described as “furious” twice and is so angry after their interaction that he orders the furnace to be heated up “seven times hotter than usual”.

The historical critical approach dates at least the final assembly of the Book of Daniel into the form that we now have it to the mid-second century BC, about the time of the Maccabean Revolt — and less than 200 years before the birth of Christ — and places its context in a way that we might better understand the story to the final authors. Scholar Norman Cohn on the Book of Daniel:

It was written about 164 B.C., probably by several authors. And its background was what was known as the Antiochan persecution of the Jews. After Alexander the Great conquered that whole area of the Near East, he left behind him a number of successor kingdoms, one of which was based in Syria. It was known as the Seleucid dynasty, and one of the monarchs, a particularly nasty one, was called Antiochus Epiphanes IV. And he did exercise a very real tyranny over the Jews. On the whole, these ancient Near Eastern empires didn't persecute people for their religion. They could be nasty to conquered peoples as conquered peoples, but they left their religion largely undisturbed. But not so this man, who desecrated the Temple and forbade all Jewish religious practices. The answer to this was that those Jews who wouldn't compromise in any way started a war, known as the Maccabean Revolt, and in the end won. And they defeated Antiochus, and reconsecrated the Temple, and it was during this war that the Book of Daniel was composed. It wasn't, however, composed by the Maccabeans. Any idea that is was a kind of recruiting manifesto is now discredited. It wasn't that. It was simply a prophetic writing. Saying that we're going to defeat Antiochus and beyond that lies a world in which the Jews will be recognized as God's chosen people, and will really dominate in their turn.

To the extent that the final composition of the story exists for its immediate audience, then the story of King Nebuchadnezzar may be read, in one view, perhaps as a subtle reference to Antiochus. Among his many other endeavors, Antiochus was fervent about the promotion of Hellenistic culture, and so one way of reading the story of Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego is as a clarion call to the Jewish readers of the mid-second century to hold fast to their cultural identity against the onslaught of pagan culture. For the Jews who read the very same Book of Daniel that we have today understood themselves, and their relationship to pagan culture, very differently than the way that Mr. Lewis understands all vaguely theistic or moral worldviews as part of one universal “Law of Right and Wrong” as he describes it in Mere Christianity.

Quite the opposite: the Jews saw themselves as spearheading a very different project across the millennia, belief in a singular, omnipotent God above all others, a project that they understood would, one day, culminate in the birth of the Mashiach.

Salvation Is From The Jews

And now the Lord says—

he who formed me in the womb to be his servant

to bring Jacob back to him

and gather Israel to himself,

for I am honored in the eyes of the Lord

and my God has been my strength—

he says:

“It is too small a thing for you to be my servant

to restore the tribes of Jacob

and bring back those of Israel I have kept.

I will also make you a light for the Gentiles,

that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.”

The Jewish project is the most audacious, ambitious project in all of human history. That The Abolition of Man and Mere Christianity give almost no special mention to Judaism, while waxing poetic about pagan concepts, is yet another demonstration of the fatally flawed construction of Mr. Lewis’ theological thinking.

Somewhere in the neighborhood of the 9th to 6th centuries before the birth of Christ, the Israelites began coalesce on a relatively untried concept to date in human culture: monotheism.8 One would imagine that Mr. Lewis would have paid greater attention to the distinction between monotheism and polytheism, beyond simply commenting on their shared similarity of theism, given that a monotheistic outlook is not only in the opening line of the the Nicene Creed that Mr. Lewis, as an Anglican, would have stood up to recite every Sunday (“I believe in one God…”) but the practice of monolatry, at the very least, is enshrined in the first commandment: “You shall have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:3)9.

For, in adopting monotheism thousands of years ago, the Israelites set humanity on a collision course with history. To begin to believe in a singular God, who could not be seen with human eyes nor take any form, and who was all-powerful, was to begin to move away from particular pagan practices — all of which were embedded in and informed by cyclical concepts of time re-initiated by the sacrifice of a human victim. As the Israelites de-paganized, they naturally began to shift away from the pagan understanding of sacrificial systems and they discovered our darkest secret: the revelation of the innocent victim. The story of Genesis 4, which not only openly and honestly tells the story of Abel’s murder by Cain — rather than mythologizing it — but has the omnipotent, transcendent God take the side of the victim and give voice to Abel is a staggering development in human understanding of the world. God’s statement to Cain in Genesis 4:10, “Your brother’s blood still cries out to Me from the ground” is perhaps the most scandalous line ever written.

Here, at long last, was a God who not only did not ritualistically demand Abel’s death, but one who was almost horrified and shocked by Cain’s violence, and took Abel’s side. However, in Mr. Lewis’ conception, there is no room for the Innocent Victim, and pagan religions are understood together with monotheism as being generally theistic and having shared moral teachings. In Mere Christianity:

If you are a Christian you do not have to believe that all the other religions are simply wrong all through. If you are an atheist you do have to believe that the main point in all the religions of the whole world is simply one huge mistake. If you are a Christian, you are free to think that all these religions, even the queerest ones, contain at least some hint of the truth. When I was an atheist I had to try to persuade myself that most of the human race have always been wrong about the question that mattered to them most; when I became a Christian I was able to take a more liberal view. […]

The first big division of humanity is into the majority, who believe in some kind of God or gods, and the minority who do not. On this point, Christianity lines up with the majority — lines up with ancient Greeks and Romans, modern savages, Stoics, Platonists, Hindus, Mohammedans, etc., against the modern Western European materialist.

In Mr. Lewis’ conception of the Tao and the aphorisms in the appendix of The Abolition of Man, the blood, bodies, and agonizing deaths of innocent, sacrificed victims to pagan gods are simply not present, because they did not live long enough to be the ones to write down the words that Mr. Lewis would record as demonstrative examples of the universal "Law of Right and Wrong”. We will never know, for example, what the last words of three children sacrificed by the Incas were, or what their opinion might have been on the “moral teachings” of the Inca culture. Instead, we have only their bodies and our scientific technology to guess at their last days:

The mummified remains were discovered in 1999, entombed in a shrine near the summit of the 6,739m-high Llullaillaco volcano in Argentina.

Three children were buried there: a 13-year-old girl, and a younger boy and girl, thought to be about four or five years old. […]

[The boy’s] clothes were covered in vomit and diarrhoea, indicating a state of terror. The vomit was stained red by the hallucinogenic drug achiote, traces of which were also found in his stomach and faeces.

However, his death is thought to have been caused by suffocation. The boy was wound in a textile wrapping drawn so tight that his ribs were crushed and his pelvis dislocated. [...]

The [teenage] girl, known as the "Llullaillaco maiden", was probably considered more highly valued than the younger children, because of her virginal status.

Tests on her long braids revealed that her coca [cocaine] consumption increased sharply a year before her death.

The scientists believe this corresponds to the time she was selected for sacrifice. Earlier research also reveals that her diet changed at this point too, from a potato-based peasant diet to one rich in meat and maize.

Dr Brown explained: "From what we know of the Spanish chronicles, particularly attractive or gifted women were chosen. The Incas actually had someone who went out to find these young women and they were taken from their families."

The results also revealed that the girl ingested large amounts of alcohol in the last few weeks of her life.

It suggests she was heavily sedated before she and the other children were taken to the volcano, placed in their tombs and left to die.10

Unlike the pagans, however, the Jews began to refuse to negotiate with all these various nature deities, and instead turned toward a mutual, self-giving covenant relationship with one God, almighty, a Creator and Lord of all who was Himself uncreated.

What resulted from this experiment was not some continuation of a universal “Law of Right and Wrong” or some iteration on a theistic project that has anything in common with, as Mr. Lewis asserts, “ancient Greeks and Romans, modern savages, Stoics, Platonists, Hindus, Mohammedans, etc.” (the etc. there speaks volumes….). Not at all. What the Jews did, in putting aside a typical pagan pantheon of nature-based deities and consolidating power into one immanent and transcendent God above all other gods, resulted in a complete upending of the entire cosmological order as it had ever existed.

Pagans did not understand humans as above nature, and this conception is entirely to be expected: nature is, in some sense, always man’s ultimate enemy, one that threatens to devour him via thirst or hunger or wild animals or disease or age even if he lives in perfect harmony with all other men. Humans did not exist without the cycle of the rain falling and the sun shining and the crops growing and the locusts staying away. These forces, to the ancient eye, were ultimately inscrutable entities upon which human life depended, and so it made complete sense for the pagan to attempt to barter with and control these entities and understand them in religious terms, and even to offer human sacrifice for such control. The rhythms of nature invite a cyclical — as opposed to progressive — understanding of time after which it is entirely unsurprising that human sacrifice would be used to initiate and vouchsafe each new cycle. In Thomas Molnar’s book The Pagan Temptation:

Indeed, all pagan religions are, with variations, pantheistic: The world-all is all that is, and since experience tell us how small a part we are of this totality, we drawn the conclusion that we are playthings of hidden forces. We are potential victims unless we learn the art of propitiating them, rending them favorable, and manuevering as so not to be crushed by them. This scramble for survival is life in the pagan cult. Pagan wisdom consists in the attempt to understand this life and to properly place human beings in the order of powers. […] The result is the tranquility of the inner life: the sage, equidistant from the tumultuous forces, internally neutral, and occupied only with the self, since the outside world is unmanageable, mostly hostile, and fundamentally meaningless.

Erich Fromm11 observes about the Jewish tradition in You Shall Be As Gods:

Man, the prisoner of nature, becomes free by becoming fully human. In the biblical and later Jewish view, freedom and independence are the goals of human development, and the aim of human action is the constant process of liberating oneself from the shackles that bind man to the past, to nature, to the clan, to idols. […] Adam and Eve at the beginning of their evolution are bound to blood and soil; they are still ‘blind.’ But ‘their eyes are opened’ after they acquire the knowledge of good and evil. With this knowledge the original harmony with nature is broken. Man begins the process of individuation and cuts his ties with nature.” (emphasis added)

The Jewish concept of an immanent transcendent God who wrestles with His own creation — as with Jacob — and allows Himself to be persuaded without any sacrifice and on arguments alone — as with Abraham — paves the way for a God who enters into a mutually binding covenant relationship with humans. As Mr. Fromm notes, at the burning bush, God introduces Himself to Moses as the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob: for He is no god of nature, but a God of history, and a God of human history.

You Shall Be As Gods:

The most dramatic expression of the radical consequences of the covenant is found in Abraham’s argument with God when God wants to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah because of their “wickedness”. […] [Abraham’s question to God] “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?’ This sentence marks the fundamental change in the concept of God as a result of the covenant. In courteous language, yet with the daring of a hero, Abraham challenges God to comply with the principles of justice. His is not the attitude of a meek supplicant but that of the proud man who has a right to demand that God uphold the principle of justice. […] With Abraham’s challenge a new element has entered the biblical and later Jewish tradition. Precisely because God is bound by the norms of justice and love, man is no longer his slave. Man can challenge God—as God can challenge man—because above both are principles and norms. […] Abraham is not a rebellious Prometheus; he is a free man who has the right to demand, and God has no right to refuse. […] God reveals himself as the God of history rather than the God of nature.

This is totally antithetical to the entire pagan cosmological order of things. In The Pagan Temptation, Mr. Molnar notes that the pagans “do not even have the concept of a good, just, forgiving, and yet powerful creator God, and they cannot even begin to fathom the God who came to human beings in Christ.”

For it is only in the Jewish project that the embers of Christianity can be kindled. As Jesus Himself says to the Samaritan woman at the well, “You Samaritans worship what you do not know; we worship what we do know, for salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22). Only with an immanent, transcendent God who prioritizes His relationship with the nation of Israel above all — and promises they will be a light to the nations and spread His worship over the globe — is the way paved for the birth of God as incarnate within His own creation, incarnate within man himself.

In Nietzsche’s The Antichrist (tr. H.L. Mencken):

The Jews are the most remarkable people in the history of the world, for when they were confronted with the question, to be or not to be, they chose, with perfectly unearthly deliberation, to be at any price: this price involved a radical falsification of all nature, of all naturalness, of all reality, of the whole inner world, as well as of the outer. They put themselves against all those conditions under which, hitherto, a people had been able to live, or had even been permitted to live; out of themselves they evolved an idea which stood in direct opposition to natural conditions—one by one they distorted religion, civilization, morality, history and psychology until each became a contradiction of its natural significance. We meet with the same phenomenon later on, in an incalculably exaggerated form, but only as a copy: the Christian church, put beside the “people of God,” shows a complete lack of any claim to originality. Precisely for this reason the Jews are the most fateful people in the history of the world: their influence has so falsified the reasoning of mankind in this matter that today the Christian can cherish anti-Semitism without realizing that it is no more than the final consequence of Judaism.

Christianity is not some iteration or final perfection of broad pagan theistic projects with their nebulous “moral teachings” that are some expression of a continually emergent Tao across many different cultures and times. No, Nietzsche’s diagnosis is wholly accurate: Christianity is the final consequence of Judaism, and it was Christianity, as the Lord Jesus Himself predicted, that incinerated all the old order of the world, together with its gods, and from such ashes something entirely new came into being.

From Bleeding Trees To Chemical Agriculture: The Desacralization Of The Universe

As I quoted above from The Abolition of Man, Mr. Lewis seems to lament too this change in the cosmological order, although he, unlike, Nietzsche, does not correctly apprehend its root cause. Where Mr. Lewis comments that a “price” is “exacted for our analytical knowledge and manipulative power [over nature],” he is actually lamenting the desacralization of the universe:

We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams: the first man who did so many have felt the price keenly, and the bleeding trees in Virgil and Spenser may be far-off echoes of that primeval sense of impiety. The stars lost their divinity as astronomy developed, and the Dying God has no place in chemical agriculture.

Where Mr. Lewis speaks of “bleeding trees” in Virgil, he is no doubt speaking of this passage in the Aeneid, when Aeneas happens upon a myrtle tree whose leaves he plucks in order to dress his altar of sacrifice (tr. Theodore Williams):

Unto Dione's daughter, and all gods

who blessed our young emprise, due gifts were paid;

and unto the supreme celestial King

I slew a fair white bull beside the sea.

But haply near my place of sacrifice

a mound was seen, and on the summit grew

a copse of corner and a myrtle tree,

with spear-like limbs outbranched on every side.

This I approached, and tried to rend away

from its deep roots that grove of gloomy green,

and dress my altars in its leafy boughs.

But, horrible to tell, a prodigy

smote my astonished eyes: for the first tree,

which from the earth with broken roots I drew,

dripped black with bloody drops, and gave the ground

dark stains of gore. Cold horror shook my frame,

and every vein within me froze for fear.

Once more I tried from yet another stock

the pliant stem to tear, and to explore

the mystery within,—but yet again

the foul bark oozed with clots of blackest gore!

From my deep-shaken soul I made a prayer

to all the woodland nymphs and to divine

Gradivus, patron of the Thracian plain,

to bless this sight, to lift its curse away.

But when at a third sheaf of myrtle spears

I fell upon my knees, and tugged amain

against the adverse ground (I dread to tell!),

a moaning and a wail from that deep grave

burst forth and murmured in my listening ear:

“Why wound me, great Aeneas, in my woe?

O, spare the dead, nor let thy holy hands

do sacrilege and sin! I, Trojan-born,

was kin of thine. This blood is not of trees.

Haste from this murderous shore, this land of greed.

O, I am Polydorus! Haste away!

Here was I pierced; a crop of iron spears

has grown up o'er my breast, and multiplied

to all these deadly javelins, keen and strong.”

The reference to Edmund Spenser is from his Faerie Queene, in which two lovers have become trees. As Polydorus notes to Aeneas, and as in the case in Spenser, the trees are not bleeding as trees. They are bleeding because, even within the logic of the story, they are actually trapped humans. The Girardian will understand that such stories are very light, thin cover-ups for human sacrifice that have taken place at special groves and trees12. In Willibald’s very credible biography of St. Boniface — he was ordained a priest by him — who evangelized to the Germanic tribes in the eighth century, he tells the infamous story of St. Boniface — who, legend says, heard that a little boy was set to be sacrificed by the pagans in the forest at Donar’s Oak (tr. George Robinson):

Moreover some were wont secretly, some openly to sacrifice to trees and springs; some in secret, others openly practised inspections of victims and divinations, legerdemain and incantations; some turned their attention to auguries and auspices and various sacrificial rites; while others, with sounder minds , abandoned all the profanations of heathenism, and committed none of these things. With the advice and ' counsel of these last, the saint [Boniface] attempted, in the place called Gaesmere, while the servants of God stood by his side, to fell a certain oak of extraordinary size, which is called, by an old name of the pagans, the Oak of Jupiter [to the Teutons, Thor]. And when in the strength of his steadfast heart he had cut the lower notch, there was present a great multitude of pagans, who in their souls were most earnestly cursing the enemy of their gods.

But when the fore side of the tree was notched only a little, suddenly the oak’s vast bulk, driven by a divine blast from above, crashed to the ground, shivering its crown of branches as it fell; and, as if by the gracious dispensation of the Most High , it was also burst into four parts, and four trunks of huge size, equal in length, were seen, unwrought by the brethren who stood by. At this sight the pagans who before had cursed now, on the contrary, believed, and blessed the Lord, and put away their former reviling. Then moreover the most holy bishop, after taking counsel with the brethren, built from the timber of the tree a wooden oratory, and dedicated it in honor of Saint Peter the Apostle.

Nor was St. Boniface alone in his encounters of sacrifice at trees in these lands. Even in the first century, Tactius noted in Germania:

“Mercury is the deity whom they chiefly worship, and on certain days they deem it right to sacrifice to him even with human victims. Hercules and Mars they appease with more lawful offerings. Some of the Suevi also sacrifice to Isis. Of the occasion and origin of this foreign rite I have discovered nothing, but that the image, which is fashioned like a light galley, indicates an imported worship. The Germans, however, do not consider it consistent with the grandeur of celestial beings to confine the gods within walls, or to liken them to the form of any human countenance. They consecrate woods and groves, and they apply the names of deities to the abstraction which they see only in spiritual worship. […]

At a stated period, all the tribes of the same race assemble by their representatives in a grove consecrated by the auguries of their forefathers, and by immemorial associations of terror. Here, having publicly slaughtered a human victim, they celebrate the horrible beginning of their barbarous rite. […]

None of these tribes have any noteworthy feature, except their common worship of Ertha, or mother-Earth, and their belief that she interposes in human affairs, and visits the nations in her car. In an island of the ocean there is a sacred grove, and within it a consecrated chariot, covered over with a garment. Only one priest is permitted to touch it. He can perceive the presence of the goddess in this sacred recess, and walks by her side with the utmost reverence as she is drawn along by heifers. It is a season of rejoicing, and festivity reigns wherever she deigns to go and be received. They do not go to battle or wear arms; every weapon is under lock; peace and quiet are known and welcomed only at these times, till the goddess, weary of human intercourse, is at length restored by the same priest to her temple. Afterwards the car, the vestments, and, if you like to believe it, the divinity herself, are purified in a secret lake. Slaves perform the rite, who are instantly swallowed up by its waters. Hence arises a mysterious terror and a pious ignorance concerning the nature of that which is seen only by men doomed to die.”

A Deutsche Welle article, intriguingly titled “Nazis and Fairytales in Germany’s Forests”, comments:

The Nazis built out the mythology that the German forest and people were one and the same. This idea served to exclude groups not deemed to be part of this unit.

This ideology propagated the view that Jews were the people of the steppes, or grasslands, and were not capable of understanding Germany's forest culture, explained Schmidt.

Indeed. It is the refusal to “understand” and participate in coughforestculturecough that the desacralization of the universe begins, and even the very organized and extremely determined Nazis could not summon back up the old ways of Germania. Once St. Boniface chops down Donar’s Oak and human sacrifice to pagans becomes prohibited, then time suddenly becomes progressive. No longer is nature to be bargained with, negotiated with, from a point of mere supplication, where, at a cyclically appointed time, a victim “without blemish” — usually a child or a young maiden — is “chosen” by the community and then “offered” to the gods in order to appease them and keep the community whole. In this new order, humans must find another way to continue living without offering human sacrifice. What is even more is that this world order is demanded by Christianity on the premise that all human life is valuable. Together, these interlinking concepts create a new cosmological order in which nature cannot be negotiated with because human life is valuable, and demands a world in which humans find new answers for the problems of existence.

This shift completely transmuted man’s relationship with nature, and with time, in ways we have not even begun to fully comprehend. As Mr. Molnar notes in The Pagan Temptation:

[Christianity] lifts [its worshipers] out of the pagan cosmic order rejected and demythified by Christianity from the start and situates them within creation, an order held together by providence and divinely ordered laws of nature rather than occult forces manipulated by secretive initiates.

It is from a more medieval-informed perspective that Mr. Lewis looks out at the disappearing dryads in The Abolition of Man, but he does not seem to fully grasp what was at work in medievalism. The entire purpose, ultimately, of the medieval project was to integrate paganism into Christianity, to retain and safely explore the symbols and tropes of paganism while holding the primacy of the Christian worldview.

Mr. Lewis’ medievalism is the reason that the pagan creatures that litter Narnia do not have “the qualities of what they are” as noted by Mr. Pageau above. What the pagan creatures “really are” is diametrically opposed to Mr. Lewis’ own Christian values. Like many people, especially in this time, Mr. Lewis seems to be drawn to the aesthetics and trappings of paganism (and the fact that imbues the world with some sense of meaning against post-modernity), but notably without all the downsides of rampant sexual immorality and human sacrifice. The reality is this, however: to defang paganism of its connection to human sacrifice by integrating it into the Christian worldview is to invite the introduction of chemical agriculture. For Mr. Lewis, even apprehending this world as “Nature” is a loss, a step down from a “primeval sense” of piety. But Mr. Lewis evinces himself as much as as perpetrator of the continually progressive modernity and unwinding of Christianity that he rails against in The Abolition of Man.

The reason that Mr. Lewis opposes the passing of the medieval world, together with its sanitized pagan tropes, is because he rejects some aspects of the modern project (although, he is more modern-influenced than he seems to realize), specifically, the loss of religious values derived from first principles, and is understandably wary of the consequent emerging post-modernity, and it is this primary concern, to be fair to the book, that frames The Abolition of Man. However, when Mr. Lewis theorizes in The Abolition of Man that Christians — as theists with some sort of “Law of Nature” — can be lined up with the “ancient Greeks and Romans, modern savages, Stoics, Platonists, Hindus, Mohammedean against the modern Western European materialist” he is fails to demonstrate an understanding of the Jewish project versus paganism, but also of the medieval project. The “modern Western European materialist” is a direct product of Christian medievalism. The medieval world naturally gives way to the modern one.

Thomas Molnar, in his 1987 book The Pagan Temptation, sees this clearly: