It’s Christmas again, a time of joy, twinkling lights, a mad rush for presents, tiny tots with their eyes all aglow, fa la la la la la, so I thought it was time to remind everyone again that culture is founded on a murder.

(Some disagree! We will discuss this nuance in January.)

In America, Christmas is celebrated with a bizarre, eclectic variety of traditions (more eclectic and strange than anyone really considers), one of which is an annual reading to the young kinder of the Dr. Seuss classic “children’s book”, How The Grinch Stole Christmas! But this book is not really about getting into that Christmas spirit; it’s really a tale of murder — and the lies that cover it up.

Dr. Propagandist

The author Dr. Seuss, known to the U.S. government in his earthly life as Theodor Seuss Geisel, was a professional propagandist before he embarked upon his much more famous career writing and illustrating books for Boomers. A strong advocate for the Second World War, he pioneered the Motion Picture Unit housed inside the United States Army Air Force, where he wrote films for soldiers who were leaving the United States for missions abroad, his two most notable short films being Your Job in Germany and Our Job in Japan.

The writing, done by Dr. Seuss, of Your Job in Germany includes such gems like:

“Every German is a potential source of trouble. Therefore, there will be no fraternization with the German people. Fraternization means making friends. The German people are not our friends. You will not associate with German men, women, or children. You will not associate with them on any terms, in public or private. You will not visit them in their homes […] Some day, the Germans may be cured of their disease, the super-race disease.”

Fraternization means making friends! One can almost imagine the Cat in the Hat saying that as he holds a rake and a cake while bouncing on a ball, but that is not all.

The purpose of these little films was somewhat like TikTok, images and audio meant to prime the mind to understand the world a certain way. Dr. Seuss’s work was essentially to take a very abstract, complex, multi-lateral war with centuries of backstory and boil it down into simple, actionable takeaways that Eddie from Kansas, who had never before left Topeka, could understand, so that he would be armed with the knowledge needed not to be fooled by hale and hearty women in dirndls bearing beer.

So it is rather fascinating when a professional propagandist turns to the art of writing children’s books for the generation of children borne by the men who followed his advice well enough to live, return to the U.S., and marry a nice girl named Sally.

Children are especially differentiated from adults in many ways, but namely in the way that they are much more impressionable and suggestible, making them fine targets for propaganda from a professional propagandist. How The Grinch Stole Christmas! is perhaps Dr. Seuss’ finest propaganda ever written, largely because it disguises itself as a children’s book, and the best propaganda of all is that which is hidden in plain sight not as an obvious film of persuasion and instruction for soldiers tasked with a relatively narrow mission, but for children who can be influenced and persuaded to see stories — the means by which we understand the world — in a certain light.

A Who-dunnit in Who-ville

The story of How The Grinch Stole Christmas! opens with an illustration of a smiling, angelic-looking little Who holding a wreath replete with a bow, below whom the text reads, “Every Who / Down in Who-ville / Liked Christmas a lot…”

Immediately, even though the Grinch ostensibly titles the story and is the main character, the story is framed not by the Grinch, but by the Whos who inhabit the city of Who-ville. It is their presence and their story that is stated first, at the very opening of the book. Our propagandist has suggested to us that the Whos are creatures without blemish, and therefore their narrative of the story of the Grinch must be unequivocally true. This is our first clue that the story we’re about to be told may be full of lies.

On the very next page, we meet the Grinch, a scowling, unhappy figure lurking alone outside a dark, unpleasant cave surrounded by snow. He is set in stark juxtaposition to the kind Whos. We are told he lives “just north of Who-ville” and, even though his illustration bears some notable resemblance to the Whos we met on the previous page, we are not told at all why the Grinch lives outside of Who-ville, whether that was always the case, or if he is even a Who himself.

He is separate from all the creatures of Who-ville, who are, as we will see, portrayed as virtually indistinguishable from each other. Immediately we have a crowd of alike persons, who live together in a community — who even though they are alike, have personhood suggested with their being a person, a “Who” — set against a singular, terrible individual who lives alone, in a cave, with a name that describes only an unpleasant quality:

The unknown narrator then tells us that, for no discernible or justifiable reason at all, the Grinch hates Christmas to the utmost degree — “the whole Christmas season!” The narrator does not wonder at or guess as to any possible fact-based reason that the Grinch would have in loathing Christmas so, or a grievance he may be justified in holding against Christmas, or any injury suffered against him that may lead to this disposition toward the holiday. Instead, we are told that the Grinch most likely hates Christmas for a flaw intrinsic to his very being — because his heart is “two sizes too small”.

Next comes Dr. Seuss’ cleverest trick of all in pitting the young audience of the book against the Grinch. The narrator tells us that the Grinch feels he must do everything in his power to stop Christmas from coming and that he is most strongly motivated to cancel Christmas because of toy presents that the children open on Christmas morning which make so much “Noise! Noise! Noise!” This is the “one thing that he [hates]! The NOISE! NOISE! NOISE! NOISE!” The illustrations show children having the absolute time of their life with a whole cornucopia of toys, from archery targets, blocks, trains, rackets, balls, Jack-in-the-Boxes, to pop guns. This two-page spread, viewed by a child, is veritable Heaven on Earth, but the narrator has subtly implied to them that the Grinch, with his irrational, visceral, fundamental hatred not only of Christmas but all the noise that these delightful presents bring, is truly a villain, the worst of the worst, vehemently opposed to the satisfaction of their greatest desires.

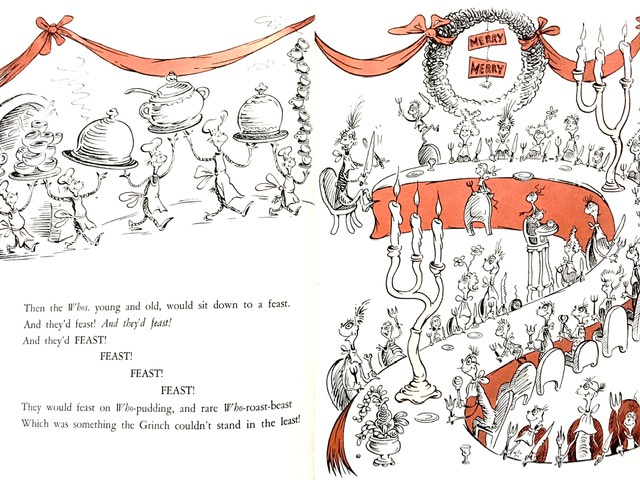

After the dreadful “NOISE! NOISE! NOISE! NOISE!” the narrator tells us, comes a great, sumptuous feast, at which dine “the Whos, young and old”. This communal feast is followed by a communion of singing, at which the Whos, “the tall and the small” stand “hand-in-hand” to “SING! SING! SING! SING!”

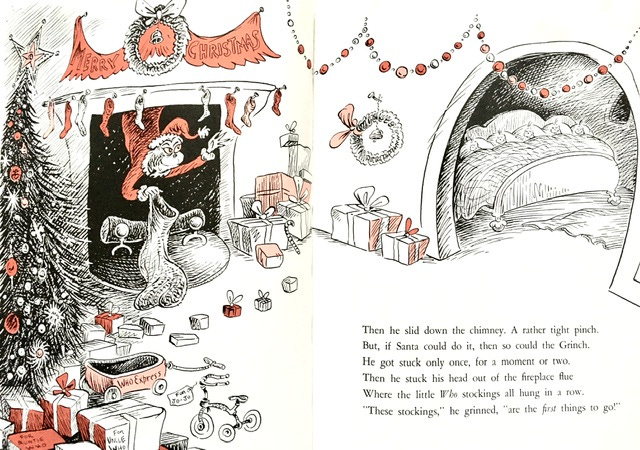

After this parade of terribles, the Grinch is finally motivated to become an imposter, a Grinch-in-Santa-clothing, illustrated in the outfit that would become the one of the most iconic American images of Christmas:

But what the narrator never tells us — or even prompts us to ask — is why, exactly, the Grinch feels the need to disguise himself at all. The Whos, after all, are supposed to be a gentle, innocent people, a fact which the Grinch never seems to dispute, at least from the narrator’s telling. He does not seem to fear personal injury or harm as a result of any discovery by the Whos, except in this one choice to disguise himself as a figure who would be widely understood as a benefactor to the community, rather than go “as himself”. Why is that? In the context of the story, we might understand it as just another additional feature of cruelty and spite that the Grinch has, but if we’re to question the narrator’s telling, we might see that the Grinch may fear, perhaps for a valid reason, going among the Whos as himself.

The Grinch then employs his dog Max as a reindeer, heads down the mountain, and begins his caper to steal all the presents from Who-ville while disguised as Santa.

Again, this scene adds to the audience’s repulsion first suggested in the Grinch’s hatred of the NOISE! NOISE! NOISE! The Grinch, with his smirking, evil sneer, is now shown embodying this worst fear of all small children, that some terrible creature would come in and steal their beautiful, shiny new toys while they sleep.

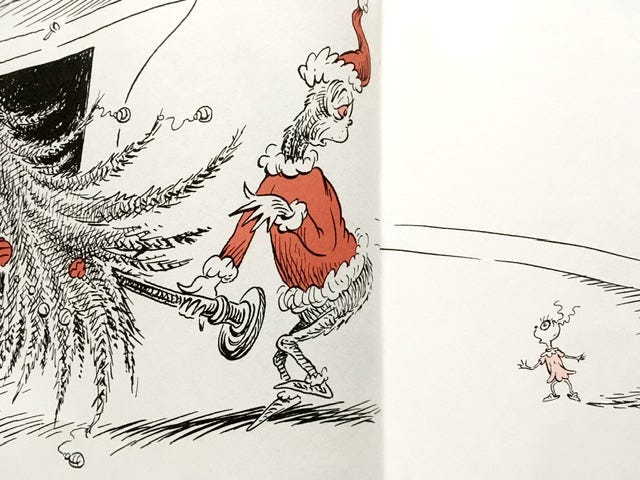

He won’t stop there, though: he goes on to steal all the food for the feast, the ornaments on the Christmas tree, and even the tree itself, stuffing all these items back up the chimney from whence he came. He is interrupted in this enterprise by the innocent little Cindy-Lou Who, who is not more than two, who has been sleeping just outside the living room and has woken up thirsty for a cup of cold water:

Cindy-Lou asks why the Grinch (disguised as Santa Claus) is taking all the presents, to which the Grinch responds with a lie that satisfies her. He gives her a cup of cold water and puts her back to bed, free to continue his dastardly work uninterrupted.

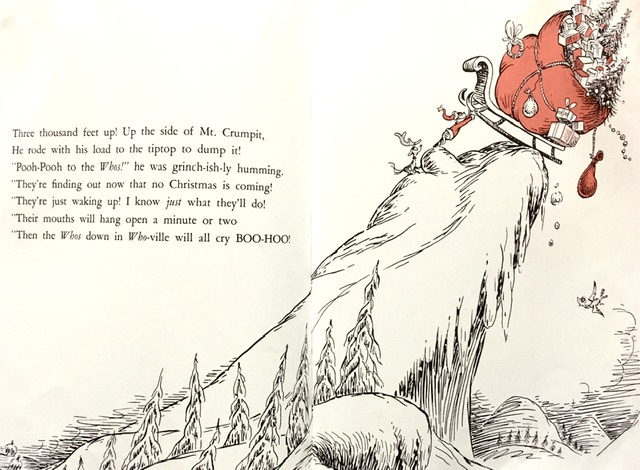

Cindy-Lou back abed, the Grinch continues to rob the place entirely, taking all the food for the feast, the log for the fire, and leaving only a speck of a crumb too small for a mouse. This pattern repeats with all the other Who houses. The Grinch’s mission complete, he hauls all his stolen goods in his feigned sleigh — “the presents! The ribbons! The wrappings! The tags! And the tinsel! The trimmings! The trappings!” — up to the top of Mt. Crumpit, “three thousand feet up” to dump it, anxiously awaiting for all the Whos to wake up to the bad fruit of his caper and cry “BOO-HOO!”:

But he finds himself in utter surprise that the sound coming from Who-Ville is not a “BOO-HOO!” but a sound that “sounded merry! […] VERY!”

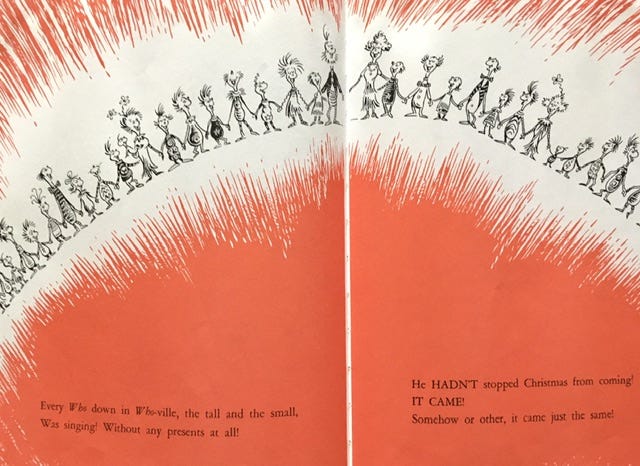

The Grinch looks down at Who-ville to see “Every Who […] the tall and the small” singing, “without any presents at all!” He discovers that he hasn’t stopped Christmas from coming, “somehow or other, it came just the same!” The illustration shows them all joined together, holding hands, in a blanket of snow (oddly tinged with red, the boldest of the book’s three print colors):

The Grinch ponders this turn of events, that Christmas has come “without ribbons […] without tags […] without packages, boxes or bags!” He “puzzle[s] three hours” on this, finally thinking of “something he hadn’t before” that Christmas may not “come from a store” but instead “[mean] a little bit more!” He is shown startled by this new insight:

This revelation leads him to bring back to Who-ville everything he stole, including “the toys! And the food for the feast!”

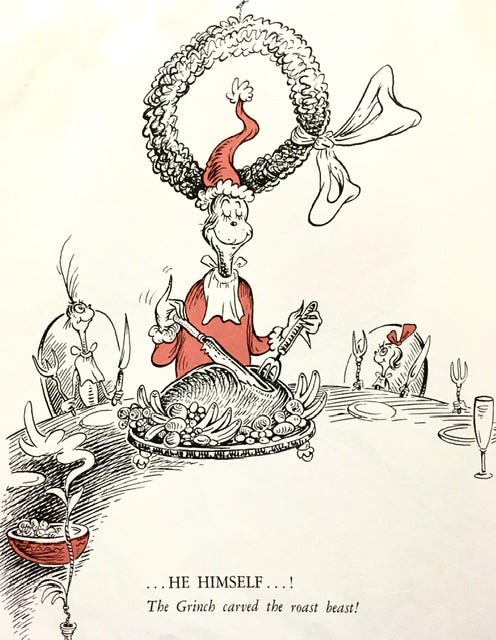

And then the book ends with the Grinch, “HE HIMSELF ….! The Grinch carved the roast beast!”, shown with the wreath in the background that parallels the wreath the Who held at the book’s very first page:

The image of the Who holding a wreath is shown again on the book’s inner pages:

Uncovering the Lies of the Whos

If, for the sake of argument, we understand How The Grinch Stole Christmas! as a mythology of Who-ville, we’ll see where the story has its breaks, the points that don’t fit just quite right, because that is a feature shared by all mythologies, which are written by the surviving Who scapegoaters over the actual, factual history of what happened to their scapegoated victim.

First, as noted above, the story is immediately framed by the Whos. This is not the Grinch’s story — even though it cleverly pretends to be — but this is the story of the Grinch as told by the Whos, imagined from his perspective. He is a separate person from the community of alike and virtually interchangeable people, but we are never told why that is.

The story is strangely not that dissimilar from that of the Gerasene demoniac, told in all the synoptic Gospels (Mark 5:1-20 below):

They came to the other side of the sea, to the region of the Gerasenes. 2 And when [Jesus] had stepped out of the boat, immediately a man from the tombs with an unclean spirit met him. 3 He lived among the tombs, and no one could restrain him any more, even with a chain, 4 for he had often been restrained with shackles and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the shackles he broke in pieces, and no one had the strength to subdue him. 5 Night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling and bruising himself with stones. 6 When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and bowed down before him, 7 and he shouted at the top of his voice, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me.” 8 For he had said to him, “Come out of the man, you unclean spirit!” 9 Then Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” He replied, “My name is Legion, for we are many.” 10 He begged him earnestly not to send them out of the region. 11 Now there on the hillside a great herd of swine was feeding, 12 and the unclean spirits begged him, “Send us into the swine; let us enter them.” 13 So he gave them permission. And the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine, and the herd, numbering about two thousand, stampeded down the steep bank into the sea and were drowned in the sea.

14 The swineherds ran off and told it in the city and in the country. Then people came to see what it was that had happened. 15 They came to Jesus and saw the man possessed by demons sitting there, clothed and in his right mind, the very man who had had the legion, and they became frightened. 16 Those who had seen what had happened to the man possessed by demons and to the swine reported it. 17 Then they began to beg Jesus to leave their neighborhood. 18 As he was getting into the boat, the man who had been possessed by demons begged him that he might be with him. 19 But Jesus refused and said to him, “Go home to your own people, and tell them how much the Lord has done for you and what mercy he has shown you.” 20 And he went away and began to proclaim in the Decapolis how much Jesus had done for him, and everyone was amazed.

Like the Gerasene demonaic, the Grinch too, dwells inexplicably in a cave separate from people to whom it would seem logical he has had some sort of previous relationship ere his change in status.

James Alison explains the story of the Gerasenes in Faith Beyond Resentment (via):

Yet there is one thing you cannot do: whether you are a townsperson or the demoniac, you cannot imagine the innocence of the demoniac. The structure which holds everything together is relatively tolerant, as is the case in most human groups. It is fairly ready to turn a blind eye to a whole lot of failings, indeed has mechanisms for reincorporating those who fail. Yet there is one point where this apparently easy-going form of life is implacably totalitarian, where there is a definition of good and evil which cannot be overturned. It never crosses your mind to question it, and indeed it cannot really be talked about, since it is what allows other things to be talked about and given value. This immutable fact which the group's imagination cannot conceive in any other way is the definition of the demoniac as demoniac. Before the arrival of Jesus, whether you are a townsperson, or the demoniac, you are all fundamentally yet tacitly agreed on what holds the whole of your order together. You are a participant in a closed system. And of course participants in a closed system do not know that they are in a closed system. It is only the vantagepoint of a system that does not depend on a hidden but secretly-structuring scapegoat which enables us to detect other systems as closed. Before the arrival of Jesus on the shores of Gerasa, such a vantagepoint was not available to you.

It seems so too, is the situation of the Grinch. Imagine that the Gerasenes had written the story of their demonaic, sometime later, after they had killed him. They would not portray themselves as a bunch of bloodthirsty, evil scapegoaters — never. Instead, they would have most certainly have written themselves up as angelic, magnificent beings, not dissimilar to the portrayal of the Whos in How The Grinch…! Have the Whos participated in the expulsion of the Grinch from the community? We are not told, but nor would we be, because this is the Whos’ story of the Grinch, not the Grinch’s story of the Whos. There is no sign of outreach to the Grinch, no sign of an attempt to have him join the community. He exists out on the cave as if he has always existed there, which is natural and to be expected, because the mythology is that this is the way that things have always been, this is the way that the order of our community has been held together. We can’t question this, or else, without Christ to help us through, we’ll unravel our whole way of being.

Then, there is the portrayal of the Grinch throughout the book, which is about as evil as you can get and still sell a book to children in the innocent, bygone years of the 1950s. He steals presents — the most heinous of all crimes for children — he seems to mistreat dogs, he hates Christmas, he hates happiness and joy. He has no redeeming qualities and there is no texture to his character, no backstory given to him. The Grinch exists as just plain bad from time immemorial, for reasons innate to his existence.

The next chink in the story is the interaction with Cindy-Lou. This is the midpoint of the story, the most dramatic part because it’s the only time the Grinch risks being discovered on the course of his story — which is planning to “steal Christmas”. It’s also, I would argue, the third most dramatically illustrated picture in the book, because the Grinch and Cindy-Lou are set in such opposition to each other, against a sparsely illustrated background which only heightens this contrast. Cindy-Lou is delicate, petite, all sweet and innocence, clothed in pink, while the Grinch is in red, overbearing in his stature.

But the strangest part of the story, as we discussed earlier, is that nothing really happens as a result of this interaction and it really should. This is the breakpoint; How The Grinch…! was, sixty years after its original publication, still ranked #61 on a list of the Top 100 Picture Books. Its longevity is due to its successful storytelling that must follow a traditional story arc, because traditional story arcs are so innate to humans that only those stories ever endure in such popularity in near-perpetuity.

The key to the success of this midpoint drama, though, it is not that Dr. Seuss breaks traditional storytelling arcs, it’s because he — our skilled propagandist — hides them so well that no one ever notices the story of what really happened. We’ll never know how evil the Grinch was, or even if he did conspire to steal Christmas, because this is the Whos’ story. We can assume, however, that the Grinch did enter Who-ville and that he was discovered by someone, and perhaps it’s even true that it was the innocent little Cindy-Lou.

But in the real story of the Grinch — not the one that has been written up, glossed over, and mythologized by the Whos — this is the point at which the Grinch is discovered in the disguise that he has been forced by virtue of necessity to wear in order to creep among the community, and subsequently strung up by the Whos for violating their community in some way, even if it was the simple act of coming into it uninvited and leaving his close-but-far-away-enough cave where he functions just nicely as a scapegoat for the Whos of Who-ville without intruding too much on their communal happiness.

The continued theft of the Grinch all the way up to the side of Mt. Crumpit — “three thousand feet up”, the narrator mentions — obscures the real history of the Grinch and the Whos, which is the Whos driving the Grinch up a cliff to push him off in a final act of scapegoating violence.

René Girard comments on the usefulness of driving scapegoated victims off cliffs in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (via):

“How can it be arranged for everyone to strike the victim, while no one is soiled by contact with him? […] Like all methods of execution from a distance -- the modern firing squad, or the community's driving Tikarau from the top of a cliff in the Tikopia myth -- stoning fulfils this two-fold ritual requirement.”

In the real history lying inside the mythology of How The Grinch…!, the Whos are shown in the communion of togetherness that has been brought about by the death of the Grinch, who is in a way like Santa Claus, a benefactor to the social cohesion of the community by virtue of his scapegoated death:

His death is further emphasized by the bright, graphic red on this page, which illustrates the blood of the Grinch spilled out for the sake of Who-ville.

The strangest twist of all in the mythologized story is the end, when the Grinch hears the singing even absent the presents or the feast, and is somehow transported from the side of Mt. Crumpit to “carve the roast beast” at the Whos’ great Christmas meal. Imagine my surprise when I was researching for this post and Wikipedia served me up this treasure of commentary:

“Dr. Seuss wrote the book quickly and was mostly finished with it within a few weeks. Biographers Judith and Neil Morgan wrote, ‘It was the easiest book of his career to write, except for its conclusion.’ According to Dr. Seuss:

‘I got hung up getting the Grinch out of the mess. I got into a situation where I sounded like a second-rate preacher or some biblical truism... Finally in desperation... without making any statement whatever, I showed the Grinch and the Whos together at the table, and made a pun of the Grinch carving the 'roast beast.' ... I had gone through thousands of religious choices, and then after three months it came out like that.’”

What’s fascinating is that Dr. Seuss himself didn’t seem to understand that the Grinch’s participation at the very center (“carving the roast beast”) in the great communal meal of Who-vile was a religious choice — the most religious of all, a participation in the sacred violence that holds the community together. But he did understand, on some instinctual level, that this ending worked — and the long-standing success of the book very much attests to that.

This too, of course, is another lie told by the self-serving, scapegoating liars of Who-ville. It’s true that, in the original history of the Grinch and the Whos, the Grinch participated at the center of their great feast. But he didn’t carve “the roast beast” — he was the roast beast. The Whos ate him in a cannibalistic sacrifice and then covered it up one day in the mythologized story. This dynamic is further reemphasized in the repeated motif of the wreath, which symbolizes the wreath-crown often worn by selected victims, whose power to restore the community’s social cohesion is like that of a monarch. And this is why, even though this story belongs to the Whos, it is framed in a kind of aweof the Grinch, their scapegoat-savior.

The Birth of New Retellings

Christianity is not mentioned at all in How The Grinch Stole Christmas! Christmas in the book is understood as some sort of generic good feeling, community, singing songs of joy — all ancillary benefits of Christianity, of course, but not the main message itself, which is the coming of the Christ child, the Savior, into the world, who will become the ultimate Eucharistic meal, the dead-and-living god and the all-forgiving, all-innocent Victim for the communion of humanity based not on self-serving lies, but on a truth that can be forgiven by the all-knowing, all-perfect Just and Merciful Judge.

But the book slips from its very pagan architecture, because it does, for all its lies, acknowledge a possible other story, even apart from the original history and the mythologized version: it contains the arc of a repentant villain who has a Road-to-Who-ville conversion and is able to join and participate in an eucharistic meal with the community from whom he has been estranged.

This is all very Christian, as shown so well in this wonderful slice of conversation between Dr. Jordan Peterson and Dennis Prager in the DailyWire’s trailer for “Exodus”:

MR. PRAGER: Yes, exactly. I want the villains to get punished.

DR. PETERSON: But do you want the villains to learn before they have to pay the ultimate price?

MR. PRAGER: That’s such a Christian question.

Mr. Prager, a devout Jew, who per DailyWire commentator Michael Knowles finds the Christian doctrine of unmerited grace a stumbling block to his own conversion to the faith, nevertheless wisely if not drily discerned that something in the tapestry of the world’s story shifted, one long-ago starry night in Bethlehem, that began a new retelling of old, once-familiar stories, leading us to a very different understanding of who the other really is in these stories, and most importantly, who, really, are we? —

You come in peace and meekness

And lowly will your cradle be;

All clothed in human weakness

Shall we your Godhead see.— M. l’Abbe Pellegrin, tr. Sister Mary of St. Philip, “O Come, Divine Messiah” (YT)

9/10 Wreaths.

You made the story of the Grinch both creepy and more profound than initially suspected in this completely uncalled for literary exercise.

(Shivers at the sight of the red colored panels and illustrations)